Pedro Castillo still stands on shaky ground

Pedro Castillo, Peru’s fifth president in five years, is in just as tenuous a position as his predecessors. Elected with a razor-thin margin, he is balancing an opposition bent on forcing him out with an extreme wing in his party determined to pull him farther to the left.

In a nutshell

- President Pedro Castillo has moderated his leftist tone

- He still faces ideological extremism on both sides

- Avoiding removal from office will be an uphill battle

After a brief honeymoon period, recently elected President Pedro Castillo faces an uphill battle to maintain Peruvians’ confidence as the country continues to confront severe economic and health crises. While moving away from the far left, the inexperienced president has committed several missteps in his initial months in office, including nominating several controversial figures as cabinet ministers.

President Castillo is confronting deeply embedded corruption and the challenges posed by Covid-19. However, his shaky legislative support and a weak popular mandate leave plenty of reason to doubt his government’s success – or even, given the country’s acute political instability, its survival.

Seismic shift

After placing a surprising first in the field of 18 candidates in the first-round election, Mr. Castillo defeated the Popular Force Party’s Keiko Fujimori in a polarizing runoff election in June. The gap was razor-thin: 50.126 percent to 49.874 percent – a margin of 44,263 votes out of 17.6 million ballots cast. Ms. Fujimori contested the validity of the results, but on July 19, after a six-week delay and just nine days before inauguration day, Peru’s national electoral court proclaimed Mr. Castillo president-elect.

President Castillo’s narrow victory underscored the country’s deep divisions.

Mr. Castillo’s unexpected success marks a seismic shift in Peruvian politics. A rural schoolteacher and trade union leader, the president’s main campaign promise was to draft a new constitution to replace the one introduced in 1993 under Ms. Fujimori’s father, the authoritarian Alberto Fujimori (1990-2000), which President Castillo argues has increased inequality. However, his left-wing platform also included broad overtures to increase the state’s role in the economy, raise the minimum wage, and invest more in health and education. He also promised to seek the nationalization of companies in the mineral, energy, and communications sectors, though he has backtracked on that vow since taking office.

President Castillo’s narrow victory underscored the country’s deep inequalities and divisions in terms of race, class and geography. Mr. Castillo nearly swept the poorer, more heavily indigenous highland Andean provinces and departments, while Ms. Fujimori carried the wealthier coast. In many electoral districts, the vote was not particularly close: in Lima’s most affluent neighborhood, 88 percent of voters picked Ms. Fujimori, while in the country’s poorest Andean region, Huancavelica, 85 percent chose Mr. Castillo.

As in other places in the region, the elections represented a rejection of the political status quo, including both traditional politicians and center-right liberalism. That does not necessarily mean, however, that voters shifted to the far left. There was a broad rejection of nearly all the candidates in the first round: the null and blank votes exceeded the vote counts for both Mr. Castillo and Ms. Fujimori. Likewise, in the runoff election, voters confronted a choice between an extreme-left candidate and a right-wing authoritarian populist with a tenuous commitment to democracy. They narrowly chose the unknown Mr. Castillo.

Three of the previous four presidents were forced from office before their terms ended.

Unfortunately for him, the Peruvian presidency is a daunting job, even for seasoned politicians with strong popular support. The only president in the last three decades who has not faced accusations of corruption is interim leader Valentin Paniagua (2000-2001), with the others facing indictments, house arrest and imprisonment. Mr. Castillo is also Peru’s fifth president in five years. Three of the previous four were forced from office before their terms ended: Pedro Pablo Kuczynski (2016-2018), who resigned in the face of certain impeachment; his replacement, Martin Vizcarra (2018-2020), who was impeached for “moral incapacity”; and his successor, Manuel Merino (2020), who resigned after only five days in office facing credible threats of impeachment. Adding to the mess, ex-president Alan Garcia (1985-1990; 2006-2011) committed suicide in April 2019 when Peruvian police arrived to arrest him over participation in the Odebrecht bribery scheme.

Limited prospects for governability

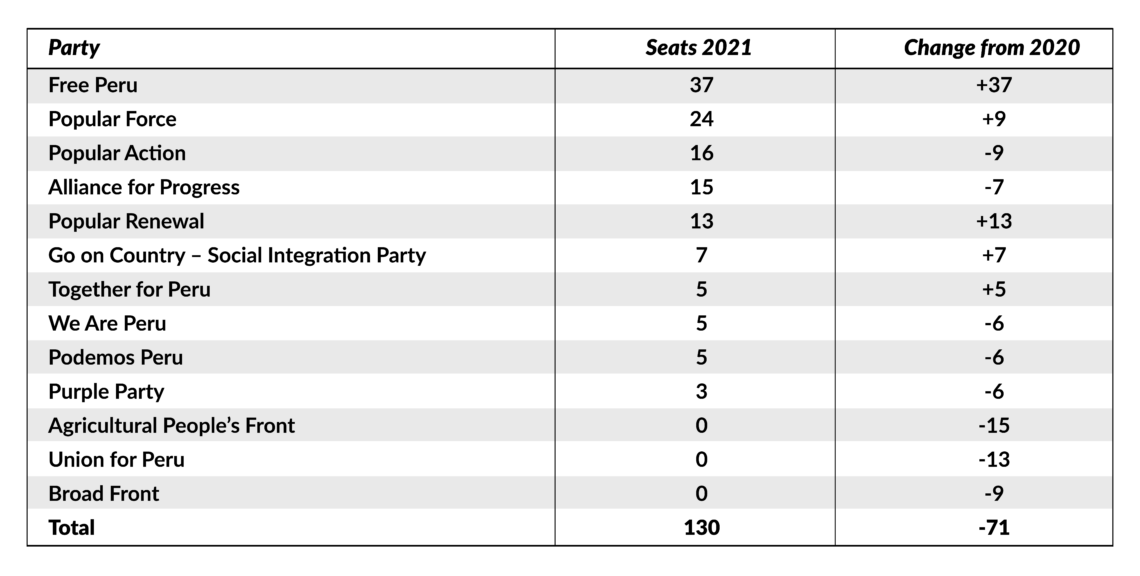

Combined, the legislative fragmentation and ideological extremism make it difficult to govern. President Castillo’s Free Peru party holds only 37 out of 130 seats, while nine other parties are represented in the unicameral legislature. Moreover, Free Peru’s far-left platform makes it difficult for the party to form a governing coalition with many of the right-of-center parties in the legislature.

Indeed, the second-largest party in Congress is the Fujimorist Popular Force, while the new far-right Popular Renewal party controls 13 seats. Moreover, congressional leadership is conservative. Predictably, President Castillo has struggled to pass his agenda.

Facts & figures

Composition of Peruvian Congress (2021 elections)

At the same time, the new president has also committed some unforced errors. He filled his cabinet, for instance, with fringe and inexperienced ministers. He appointed avowed Marxist and alleged terrorist sympathizer Guido Bellido as prime minister and former left-wing guerrilla Hector Bejar Rivera as foreign minister. This sparked protests and coincided with intense scrutiny by prosecutors over allegations of corruption or misconduct by several of President Castillo’s political allies, including Free Peru leader Vladimir Cerron. In this context, the appointment of a moderate economist, Pedro Francke, as economy and finance minister may have represented a conciliatory gesture to the political center.

Further attempts to moderate his policy positions have provoked some backlash. On October 6, President Castillo overhauled his cabinet, replacing the controversial Mr. Bellido and six other ministers in a move that significantly moderated his government. While this may have appeased the opposition and calmed investors’ nerves, it also alienated his party base and triggered recriminations. While it is unlikely that Free Peru would oppose the government, the fraying of this relationship is likely to further weaken President Castillo’s already limited ability to build legislative majorities. There is a risk that by purging his cabinet of ideological hardliners, he has estranged himself from one of his only reliable legislative allies.

Still, “moderate” is a relative term for President Castillo, as his administration is already starting to make good on its campaign promise to increase state involvement in extractive sectors. In September, while he was still prime minister, Mr. Bellido threatened to nationalize the Camisea gas fields (one of Peru’s largest energy projects) unless the international consortium that runs it agreed to renegotiate the amount of royalties it pays to the government.

‘Moderate’ is a relative term for President Castillo.

President Castillo threw cold water on Mr. Bellido’s threats of nationalization, although his refutation seemed focused on promising a fair and legal process rather than a total rejection of the idea. The process is part of a broader plan to construct a national gas pipeline network and make the distribution of natural gas a key state policy. President Castillo also plans to restart a project to build a gas pipeline in southern Peru.

Scenarios

Predicting likely policy outcomes for the Castillo administration is particularly difficult given the government’s disorganization and opacity in its decision-making. Despite the tilt toward moderation, there is little reason to believe the president has a grand strategy. Since the cabinet reshuffle, Prime Minister Mirtha Vasquez has stated that redrafting the country’s constitution is no longer a priority, despite it having been a key campaign promise.

As demonstrated by its treatment of Camisea, perhaps the only policy that seems assured is government renegotiation of contracts with gas and mining companies. Ensuring broader benefits from Peru’s extractive industries and putting them toward the country’s development has support across the political spectrum. Government leaders seem especially enamored of the Chilean and Colombian models of taxing mining companies on “excessive” profits, especially now that the price of copper is high. At the same time, and despite his fiery rhetoric, there is no indication that President Castillo has any plans to expropriate companies or seize their assets.

Ultimately, President Castillo will have to overcome at least two big problems if he hopes to remain in office: a radical base that dislikes his shift toward moderation and an equally radical opposition that will not believe any signs of moderation and will try to undermine and eventually remove him.

There are at least three possible outcomes. In the first, President Castillo forges a broad centrist coalition to pass legislation, break with the extremists in his party and deftly steer the country out of its political malaise, allowing him to increase his base of support and hold onto power. In the second, there is a breakdown of governance during the executive-legislative battles to come, leading to impeachment attempts competing against legislative dissolution. In the third, the president heads off these possibilities by closing off channels of contestation and accountability.

A centrist coalition

In the best-case scenario for the country, President Castillo would get his government organized and create a broad centrist coalition to pass legislation. To an extent, he has already pivoted toward governability and dialogue through his cabinet change since few of his previous ministers were holding him back from cultivating a better relationship with some members of Congress. In this scenario, the cabinet change and the positive media coverage will force the Congress to work with President Castillo on at least a temporary basis. If the president is a quick learner, he could leverage this support toward increasing his public standing and pushing for broadly popular policies, and manage to complete his term in office.

However, nothing before to this most recent cabinet change appeared to point in that direction, and President Castillo’s inexperience and prior public missteps make a broad and enduring political coalition improbable.

Authoritarian consolidation

A more worrying but unlikely scenario is President Castillo closing off channels of democratic contestation amid attacks from the ideological extremes. With Ms. Fujimori questioning his legitimacy, President Castillo may seek to consolidate power to stay in office. This could force him to remove judges, push for the referendum on rewriting the constitution and install military commanders who support his agenda. In this scenario, he would replace moderate ministers and advisors with more extreme figures. This outcome would represent a severe threat to Peru’s democracy, but President Castillo does not appear determined to take this path for now.

Dissolution of Congress

Perhaps more likely is the possibility that President Castillo will dissolve the legislature to force new elections if Congress blocks his policies. Peru’s constitution establishes conditions under which the president may be removed from office but also includes clauses that allow the president to dissolve Congress “if it has censured or denied its confidence to two cabinets.” Should this happen, new elections must be held within four months. Martin Vizcarra, confronting legislative gridlock, chose just this path in September 2019.

However, the National Congress, aware of this possibility, approved a bill in September to limit the president’s power to dissolve the legislature. The legislation will probably wind its way to the country’s constitutional court before it can become law.

Impeachment

Given the country’s recent history, the president’s weak position and the intransigent Fujimorista opposition, the most likely outcome (more than 50 percent) is that President Castillo will be impeached or otherwise removed from office before his term is over. Since 2017, Peruvian politicians have repeatedly invoked articles of impeachment against their president.

The right-wing factions of Congress see President Castillo’s cabinet change as a mirage that must be rejected and fought. Led by Ms. Fujimori, they are attempting to undermine Mr. Castillo and push him from office in early 2022.