The curse of being stuck between oil and debt

Africa’s second-largest oil producer had been going through a rough patch since the 2014 oil-price collapse – and then came the pandemic. Prospects for post-Covid recovery in Angola are hampered by crippling foreign debt and lack of progress in economic diversification.

In a nutshell

- Angola has not been badly affected by the pandemic

- However, Covid-19 took an economic toll on the country

- Depressed oil prices and debt pose dire challenges

Battered from years of slowdown and recession, Angola’s economy was hit twice in 2020: by the Covid-19 pandemic, and the fall in oil prices. The latter severely deepened the overall recession caused by the former.

As for the pandemic, Angola has not been gravely affected. By mid-March 2021, it registered less than 22,000 infections and slightly over 500 fatalities in an overall population of 33.5 million. These are relatively modest figures, even if lowered by underreporting caused by insufficient testing and registering.

However, the economic consequences of Covid-19 have proven considerable. The social distancing measures and restricted travel took a toll on small and medium-sized businesses. The pandemic also overburdened the country’s fragile healthcare system.

Oil price drama

The most devastating effect, however, was the slump in oil prices. Brent crude represents 95 percent of Angola’s exports and brings 55 percent of its fiscal revenue. When its price nosedived during the worldwide economic contraction – in April 2020, it dipped under $25 per barrel – Angola reeled.

As recovery began in the summer and fall, the conditions improved. By the end of 2020, oil prices reached the $50 mark, and Angola closed the year with 473 million barrels of crude oil exported. But the damage was done: the average decrease in price of about a third compared to 2019 translated into a proportional drop in revenue.

Facts & figures

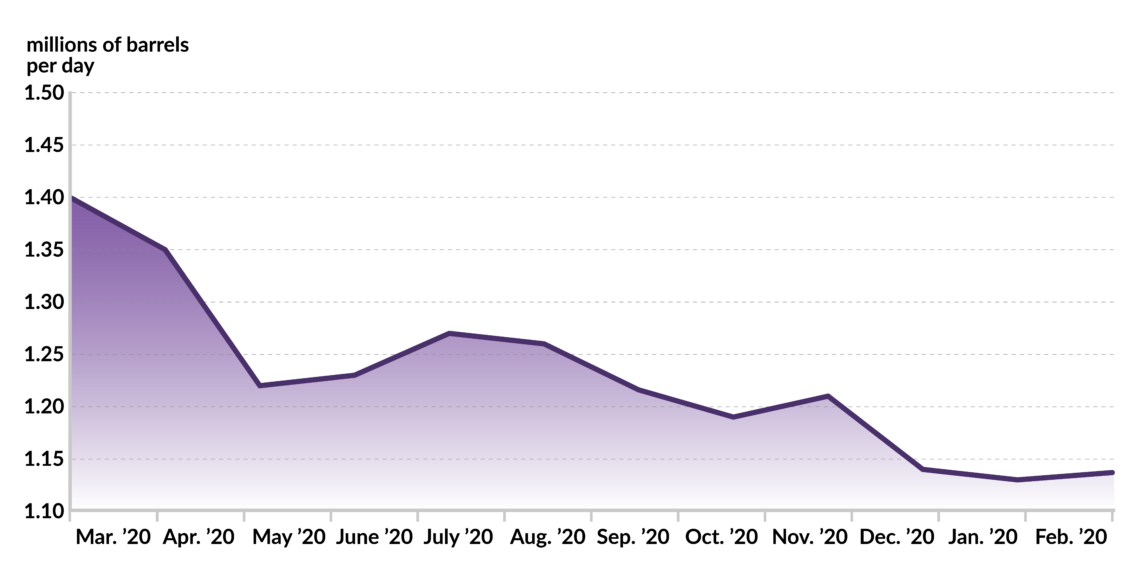

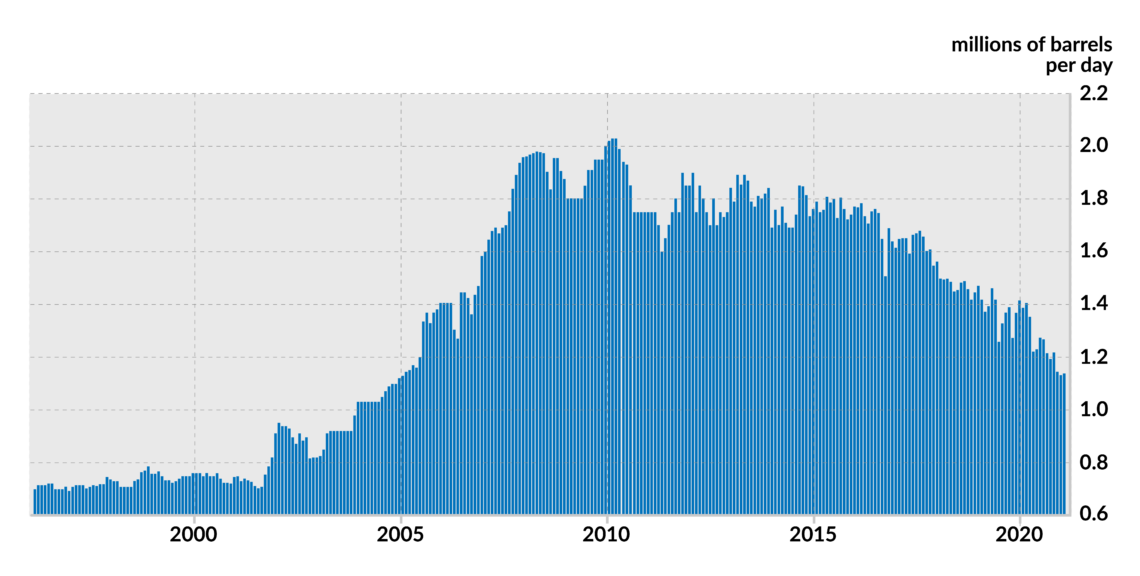

The production also declined: the average of 1.29 million barrels per day in 2020 was a far cry from the levels of the previous decade when Angola’s output surpassed 1.8 million barrels a day. But the drop in production is also a result of years of insufficient investment in exploration and developing new production fields. The consequences of this neglect are now tangible.

Facts & figures

In Angola, it is difficult to estimate the difference between the cost of producing oil and its price on international markets. The wide diversity of exploitation conditions in its various operating blocs makes calculating the averages highly complex. Nevertheless, operating costs have risen significantly with the pandemic.

Angola’s long-term production decline was made worse by OPEC’s supply cuts in 2020, as the pandemic destroyed a third of global demand. Initially, Angola was reluctant to comply fully with the policy but relented under pressure from the organization. As the country’s production capacity continued to shrink, it reached the point when it was no longer able to meet its reduced output target. In December 2020, Angola’s daily production was more than 80,000 barrels shy of its allowance and the gap widened each month. This situation will have repercussions in 2021.

Angola hopes to improve its energy balance, presently aggravated by expensive imports of refined oil products.

There is light at the end of the tunnel, though. Thanks to 2018 legislation aimed at reviving the oil industry, investment has begun to return to Angola. France’s Total and Italy’s Eni have resumed activity there; in July 2018, Total initiated a $16 billion investment in Koambo’s ultradeep-water offshore project with a production capacity of 230,000 barrels per day to develop estimated reserves of 650 million barrels.

In another important development, Qatar Petroleum has been authorized by Angola’s government to assume a 30 percent stake in Block 48 of the ultradeep water Lower Congo Basin; in the farm-in agreement, the operator is Total with 40 percent, and state-owned Sonangol EP has 30 percent.

In mid-March 2021, oil prices hovered close to $63 per barrel. However, due to the expected economic rebound the United States Energy Information Administration (EIA) anticipates ramped-up production and downward pressure on prices to an average of $58 per barrel in the second half of the year. Assuming Angola’s per-barrel pumping cost between $25 and $30, its margin can still be promising.

Angola also hopes to improve its energy balance, presently aggravated by expensive imports of refined oil products. The long-planned refinery on Malembo plain in Cabinda, with an ultimate capacity of 60,000 barrels per day, should make a significant financial difference.

Shrinking economy

Facts & figures

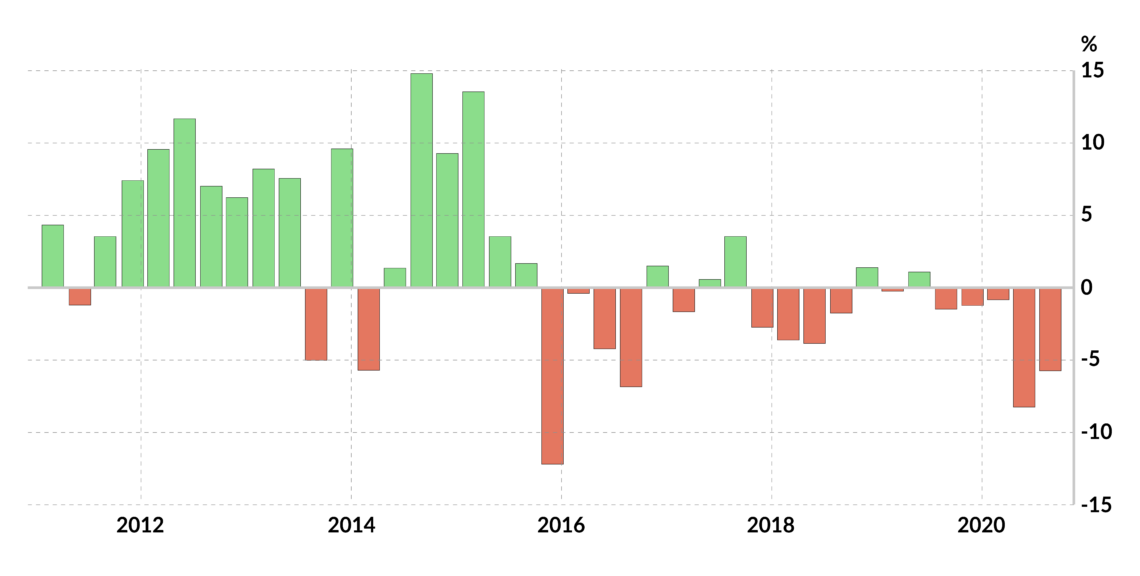

According to Angola’s National Statistics Institute, between 2015 and 2019, the accumulated fall of Angola’s GDP was 5 percent. In 2020, with the Covid-19 pandemic, it should again be around 5 percent, resulting in an overall decrease of some 10 percent. On the other hand, faced with such headwinds, the government demonstrated an ability to make difficult financial adjustments, and the country ran overall primary budget surpluses in 2018 and 2019. In 2020, this became a deficit of 3.1 percent of GDP. In its proposed 2021 budget, the Angolan government aimed to shrink this deficit to less than 2 percent of GDP. Fitch Ratings projects 2.2 percent, still a decent result given the circumstances.

Angola’s President Joao Lourenco, a former defense minister and political insider during the 38-year rule of his predecessor, was elected in 2017 on promises to institute higher standards of honesty and equality in the country’s economy and public life. His anti-corruption measures have caused trouble for many members of the ruling elite and families previously perceived as “untouchables,” which earned him a degree of credibility and genuine support among the electorate. The leader is aware that his government’s foremost task is to improve the living conditions of the population. And it needs to act quickly.

Agriculture is pivotal to all schemes to decrease Angola’s imports and create jobs for the growing active population.

The government faces a daunting task. On top of the constantly diminishing oil revenues, there was an accelerated depreciation of the national currency, the kwanza, with the inevitable rise in the prices of imported essential goods. Inflation rose from 7.3 percent in 2014 to 19.6 percent in 2018. And after a slight recovery in 2019, it hit a three-year high in December 2020 of 25.2 percent (and 21 percent overall for the year). No improvements are expected for 2021.

For many years to come, the oil sector will remain critical to Angola’s economy. Economic diversification has been a concern for the president and his team, but they are aware that this is a tortuously slow process at best – even more so if agriculture is to be at the heart of it. And agriculture is pivotal to all schemes to decrease Angola’s imports and create jobs for the growing active population.

Debt monster

Another critical component of Angola’s economic and financial equation is public debt. It is very high, both in absolute terms and as a percentage of GDP. Roughly two-thirds of the debt is external, and a third is internal.

Chinese state-owned banks hold a significant share of the external debt. This is for historical reasons: when the Angolan civil war ended, the U.S. and Europe showed little interest in financing projects and investing in the devastated country. Taking its first steps in its Africa strategy, China filled the void with its acquisition of energy and mining resources and loans in exchange for public works contracts for Chinese construction companies. Soon, it took the lead in financing governmental projects on the continent.

Between 2010 and 2014 (the year of oil price collapse), Angolan external public debt remained stable at about 33 percent of GDP. In 2015, it skyrocketed to 60 percent and further to 75 percent in 2016, due to the massive Chinese loans. In 2018, the first full year of Mr. Lourenco’s presidency, the external debt had already reached 90 percent of GDP. In dollar terms, it went from around $36 billion in 2015 to $44.5 billion in 2018. According to Trading Economics, it reached another historic peak of $48.8 billion at the end of last year.

The country struggles not to exceed the 100 percent GDP barrier, a major restraint to the budgetary room for maneuver.

Despite a demanding set of challenges, the country’s financial performance was better than many expected.

The above figures do not include the external debt of state-owned companies, such as Sonangol and TAAG Angola Airlines. If their combined $5.5 billion in debt is added to Angola’s internal debt, the total reaches $20 billion.

Chinese banks – led by the China Development Bank – are holding $22 billion, or 43 percent of Angola’s outstanding external debt. The United Kingdom is the second-largest creditor, holding $14 billion (27 percent); this includes the debt held in Eurobonds registered in the UK but not owned by UK investors. International organizations such as the IMF and the World Bank stand as other important creditors, followed by individual countries: Israel, Ireland, Portugal, Spain, and Japan.

This is the difficult legacy inherited by Vera Daves, the country’s 37-year-old finance minister. She took office in October 2019 and soon had to deal with additional financial strains related to the Covid pandemic. Aside from a sharp decline in state revenues, unexpected expenses related to the health crisis had to be added to hefty debt-servicing costs, consuming about half of the state budget. At the same time, Minister Daves was tasked with improving foreign currency reserves. Despite such a challenging set of circumstances, the country’s economic and financial performance was better than many expected.

The International Monetary Fund increased its loans for Angola from $3.7 billion to $4.4 billion – the largest amount to date approved by the IMF to a sub-Saharan African country. However, the most critical negotiation for budgetary relief was with Chinese creditors.

Unlike other lenders, China shuns multilateral solutions, favoring bilateral negotiations on a case-by-case basis with debtor countries. According to reports by Portuguese news agency LUSA, Chinese creditors agreed to defer more than $5 billion in debt and interest payments. Moreover, Angolan negotiators were able to secure a moratorium on an additional $1.5 billion in debt to G20 countries.

Scenarios

Return of growth

If IMF estimates prove correct after the 2020 recession, Angola should experience 3.2 percent GDP growth in 2021 and around 3.4 percent until 2025.

The firming in oil prices, well above the level of $39 per barrel assumed in the 2021 state budget, leaves room for some optimism. But tortuous roads lie ahead, and much can still change depending on OPEC policies in the short run and on new investment inflows in the long run.

Angola’s failure to identify new oil reserves in years past bears heavily on its industry’s current situation. The exploited fields feature considerable depletion rates. Fitch Solutions estimates that Angolan oil production would stand at 1.03 million barrels per day within 10 years at the current depletion pace. The exhausted deposits need to be replaced with new ones. The greatest potential is in the deep and ultra-deep offshore reserves, which require expensive, high-risk investments.

Under current market conditions, most of the companies that operate in Angola are only willing to continue their commitments to the existing projects. If the companies do not change their position, Angolans may see their oil output drop steadily until 2030.

If history is any guide, disinvestment by major operators tends to lead to economic and subsequent political shocks. For now, the risks for Angola are mitigated, as the presence of the two majors in the country – Total and Eni – seems secure. In fact, ongoing operations – particularly in the Total-led Kaombo field (Block 32) producing almost 150,000 barrels per day – support oil production growth estimates of 2 percent and 4.2 percent for 2020 and 2021.

Another encouraging development is the move by ExxonMobil to exploit Blocs 40, 44 and 45 in the Atlantic Namibe Basin off southern Angola; the contract was signed in Luanda in October 2020.

Badly needed FDI

The Angolan government knows that it needs private foreign investment to diversify its economy. Only by developing such sectors as agriculture, mining and manufacturing can the country hope to ease its dependence on hydrocarbon exports. But for such investment to come, Angola would need to become a de facto reformed investment destination. The magnitude of the task is tremendous, particularly considering the scale of corruption during the former president’s final years and the vested interests still in place.

Governance

International investors welcomed President Lourenco’s anti-corruption crusade early on in his tenure. The new administration moved swiftly against parts of the old regime, but many others tainted by corruption remain untouched. Changing the status quo is not easy in Angola, and things do not happen overnight. The president has tried to strike a balance between swift crackdowns and the need to respect legal procedures that sometimes delay and obstruct justice. He struggles on two fronts – involving his own party and the opposition.

The overarching desire to preserve the rule of the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), the country’s largest legacy liberation party, dictates a cautious approach. Cleansing party structures aggressively and pursuing fundamental reforms would have earned Mr. Lourenco many cheers inside and outside the country. The MPLA, however, is his party; the president needs its structures to rule.

What he does not need is internal strife. Angola can ill afford more political conflict when its economic future hinges on attracting foreign direct investment. Recently, violence erupted in the diamond-rich Lunda North Province. A police station was attacked, prompting a swift reaction from the local authorities and government forces.

With this in mind, President Lourenco has been letting go of some misdeeds of the past but tolerating no new ones. Politically, this is a reasonable approach, but it will not bring fruit fast enough for voters who need money and jobs now. Expectations are running high for the MPLA Congress in December, where the president is expected to get rid of some of the party’s political ballast.

And then there is the opposition, which is trying to unite its different branches. Its main force is UNITA (a Portuguese acronym for the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola), the movement founded by the famous guerrilla leader Jonas Savimbi, who was killed at the end of the civil war.

Recently, UNITA leader Adalberto Costa Junior, former MPLA dissident Justino Pinto de Andrade and former UNITA dissident Abel Chivukuvuku announced their intention to build a single political front against the MPLA. However fierce the opposition may sound, there is little risk of it going outside the tracks of the legal democratic process. Leaders on all sides are aware that it would be a disaster for the country and its international image.

Internal strength

Angola’s key competitive edge over other sub-Saharan African countries is in having overcome tribal divisions and advanced modernization of its politics. A quarter of a century of civil war forced urbanization and accelerated the forging of a melting pot that produced today’s Angolan society. The country now offers relative stability compared to some of its neighbors.

This explains the tough and swift reaction to the events in Lunda. The president was adamant in advising his political competitors not even to try to exploit the incidents. Given Angola’s very long civil war and both government and opposition leaders’ personal experience, nobody dares to put at risk today’s peace and stability.