Accelerated change in Sub-Saharan Africa

In some parts of the world, Covid-19 set off new economic or political trends. In Sub-Saharan Africa, the pandemic sped up those that were already in place. China’s influence on the continent is set to increase, while the U.S. and Europe lose sway.

In a nutshell

- The pandemic could worsen African indebtedness

- It will also drive innovation and market-based solutions

- Post-pandemic Africa will thrive on China's influence

This GIS 2021 Outlook series focuses on the opportunities that stem from the upheaval of the past year.

Unlike other regions of the world, Covid-19 has not generated new political or economic trends in sub-Saharan Africa. Instead, it has accelerated the ones that were already sweeping through the region – increasing both the risks, like indebtedness and financial stress, and the opportunities, like digital innovation and regional integration.

As the world grapples with uncertainty and complex new geopolitical shifts, how countries across the region manage these risks and opportunities will determine whether reform and transformation processes can succeed.

Risks exposed

While sub-Saharan Africa has seen a relatively low number of Covid-19 cases and deaths, the pandemic exposed the region’s dependence on external financial flows, from commodities trade, to tourism, foreign direct investment (FDI), aid and remittances. The disruption of global supply chains and business, restrictions to movement and the recession that followed have taken a significant economic toll on oil exporters like Angola, remittance recipients like Gambia or tourist destinations like Rwanda, Cabo Verde and Tanzania.

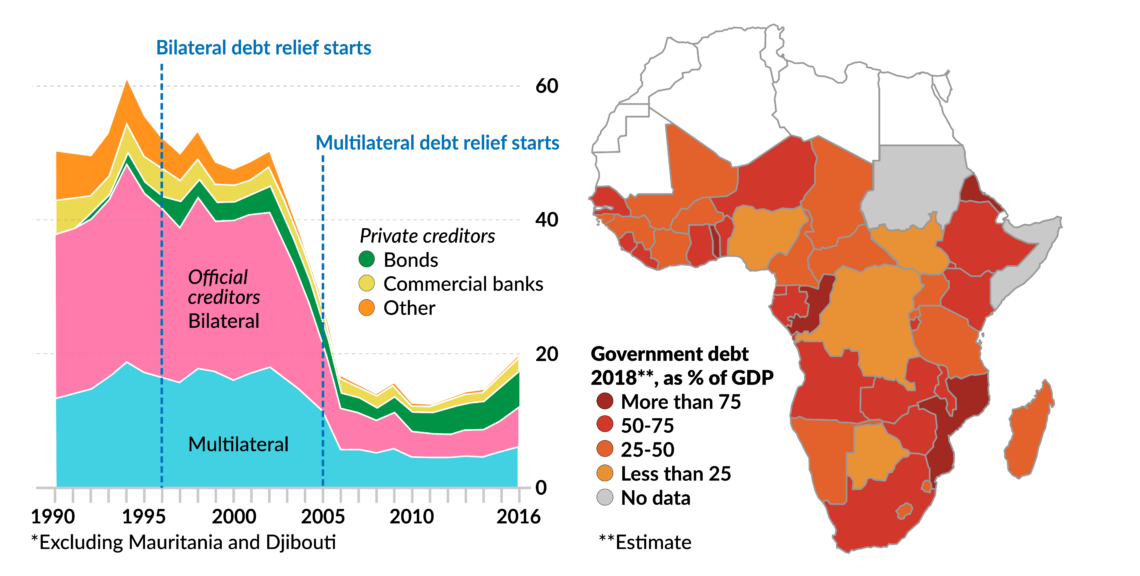

Recent events also exposed the region’s high indebtedness. Even before the pandemic, 40 percent of the countries in the region were either in or at risk of debt distress. For many, the danger of further downgrades and defaults has increased. In November, Zambia became the first African country to default on its debt since the pandemic began. Ghana, Angola, Kenya and Mozambique are also overexposed, reflecting the systemic nature of the problem: Africa spends around $40 billion per year on servicing its debt

Over-indebtedness and low investment rates are two sides of the same coin.

In May, the World Bank and the G20 implemented the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), under which 30 African countries could suspend debt repayment on official bilateral credit until at least June 2021. This program alone, however, will not keep financial distress at bay. Unlike what happened in the 1990s with the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative, when multilateral creditors agreed to erase the debt of several poor countries, bilateral and market-based creditors have now taken on a much larger share of the region’s total external debt. The share of debt owed to commercial creditors increased from 17 percent in 2000 to 40 percent in 2019. For countries like Benin, whose main creditors are in the private sector, this moratorium is a poisoned chalice that may compromise their return to the markets.

In sub-Saharan Africa, overindebtedness and low investment rates are two sides of the same coin. The need to fill the region’s financing gap became clearer as governments struggled with falling revenues due to falling trade, remittances, aid and FDI flows. The World Bank pledged $50 billion in financial support for African countries. By October, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) had handed out $17 billion to sub-Saharan African nations, a volume which far exceeds payouts made in previous years. However, the IMF still estimates the region’s funding gap at $290 billion over the next three years. Attracting investment is crucial for post-pandemic Sub-Saharan Africa.

Seizing opportunities

While the prospects for recovery are murky (the IMF predicts “modest” growth, 3.1 percent in 2021 after contracting by 3 percent in 2020), for some countries and sectors in sub-Saharan Africa, the crisis may speed up reform and innovation, thanks to a combination of political dynamics, economic trends and geopolitical shifts.

On the political front, some sub-Saharan African countries may benefit from a comparative advantage. Western countries curtailed their citizens’ rights with their lockdowns. In sub-Saharan Africa, many countries opted for looser measures, while in others rights were already restricted. In both cases, the political consequences of the pandemic may be easier to overcome.

A second important factor has to do with diverging economic trends. In developed economies, governments and central banks are trying to spend their way out of the crisis, expanding the role of the state as they go. Economic freedom had already been steadily increasing, but for post-pandemic Sub-Saharan Africa it has become clearer than ever that a bigger and more active private sector is necessary to increase economic resilience.

Facts & figures

Moreover, the current crisis has not undermined the region’s growth drivers. One of its biggest advantages is its ability to leapfrog stages of technological development. In several countries, the pandemic has sped up digital transformation in sectors like healthcare, trade, insurance and digital banking. Micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs), which account for around 80 percent of the region’s economic activity, have led the innovation and adaptation processes.

While African entrepreneurs and investors face several obstacles, including lack of adequate infrastructure and an incipient middle class, they may be more prepared to adapt, restructure or shift their business models according to market demands. Furthermore, they may profit from the momentum generated by a broad consensus, both within and outside the region, that the private sector should play a central role in the region’s recovery. Finally, ultra-low interest rates in other regions could send investors looking for higher yields flocking to markets like sub-Saharan Africa’s, which are considered riskier.

The geopolitical shifts could also drive growth and development in the region. China has readjusted its strategy in the great power competition. To ensure resilience against external shocks, it wants to move away from markets and supply chains over which it has less control and focus on those that it can influence more. That means African countries are expected to attract even more attention from Beijing.

China’s mask diplomacy will give way to vaccine diplomacy.

One of the major focuses will be on health, with a new emphasis on the “Health Silk Road” first proposed in 2017. Throughout 2021, “mask diplomacy” will give way to “vaccine diplomacy.” Especially given its exposure to African debt, Beijing is expected to invest more cautiously, favoring public-private partnerships and smaller projects. However, the era of Chinese megaprojects in Africa is not over yet. A Chinese firm is set to build a $2 billion hydropower plant on the Nile in Uganda, while another is helping to finance the construction of a $3 billion thermal power plant in Zimbabwe.

Scenarios

Three key factors will determine the course of the post-pandemic era in Sub-Saharan Africa: geopolitical trends, digitization and countries’ ability to increase their self-reliance. The baseline assumption is that recovery will speed up in the second half of 2021, as governments in Europe, remove restrictions thanks to effective vaccination campaigns.

Increased Beijing influence

Under the most likely scenario, Beijing will maintain or even increase its role in the region, offering strategic partnerships to African countries, including projects that integrate the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) into the Belt and Road Initiative launched in 2015. China may also play an important role in developing digital infrastructure in the region, including 5G networks. The ties it builds with countries in sub-Saharan Africa could have long-lasting consequences, not only economically but also politically, as they could strengthen authoritarian regimes.

A scenario under which the EU and the U.S. assume a more prominent role in Africa’s development is less likely. In recent years, both powers have been losing influence in the region. Looking to the near future, they will focus on domestic challenges.

After a brief interruption due to the pandemic, efforts toward regional integration, under the AfCFTA, will likely resume. Several countries are already reducing visa requirements for African citizens to speed up the recovery. Resilience to external shocks, strengthening regional value chains and increasing self-reliance are expected to become major concerns guiding this process.

Under the most likely scenario, these efforts will help strengthen the region’s manufacturing sector, which was hamstrung by the pandemic. Industrial powerhouses like South Africa, Nigeria and Ethiopia (provided that the Tigray conflict ends in 2021) and relatively technologically advanced countries like Kenya, Rwanda and Ghana, could benefit from such a process.

Business-as-usual

Another key factor will be whether African countries can break the vicious cycle of indebtedness. Debt relief and debt swaps are the options currently on the table. Debt forgiveness is less likely, considering that much of the debt is bilateral or commercial. Under a business-as-usual scenario, countries like South Africa, Zambia, Angola and Namibia could be in deep financial trouble by 2021, when the payment suspension is lifted. As previous initiatives suggest, however, debt pardoning or relief without structural transformation would only be a temporary palliative.

The trends that the pandemic reinforced will generate opportunities which, if seized by decision makers, may inaugurate a decade of growth and development. Some countries – due to ongoing conflict, extreme poverty or bad governance – will be unable or unwilling to start reform and transformation. Countries with better governance, more diversified economies and improved business environments are better prepared to navigate the challenges ahead. Countries like Ghana or Cote d’Ivoire are best placed to embrace the opportunities of 2021 and beyond.

The global recession will hit poorer, resource-dependent countries with inefficient governments more severely. In the post-pandemic era, Sub-Saharan countries are less prepared to engage in much-needed processes of reform and adaptation.