The energy sector’s lessons for healthcare

The Covid-19 pandemic has made it clear that businesses need to take a hard look at their supply chains and governments need to address the shortcomings of the healthcare sector. Here, the energy sector has some lessons that can be implemented.

In a nutshell

- The crisis has revealed huge vulnerabilities in supply chains

- Governments are likely to renationalize some infrastructure

- Energy security measures hold lessons for the health sector

The COVID-19 crisis has caught Europe off guard, even though the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, the 2002-2004 SARS epidemic and the 2012 MERS outbreak had already highlighted major shortcomings. The disease has exposed a lack of international cooperation and national preparedness. Measures put in place to contain the spread of the virus have caused shortages of medical equipment, not to mention basic medicines, and they will also affect critical infrastructure as the crisis drags on.

The fight against coronavirus created an urgent need for laboratory supplies, testing kits, masks, respirators, ventilators and other supplies, straining the EU’s healthcare systems. Previous epidemics had already revealed the need to create a robust inventory system for medical equipment. Many national security documents have listed pandemics as a major security threat. However, most states failed to come up with a concrete plan in the event of a highly contagious disease.

By mid-March, the scramble for essential supplies began in earnest. Some 24 countries (including the United States and European nations) had prohibited the export of certain medicines or equipment. Global competition for necessary material grew fiercer. Even the U.S. found itself hard-pressed. Its Strategic National Stockpile, for instance, contains less than 1 percent of the medical masks and less than 10 percent of ventilators experts estimate the country will need to deal with the pandemic.

Companies’ ‘just-in-time’ global supply chains contain serious vulnerabilities.

Washington also reportedly considered asking German biotech firm CureVac AG to relocate to the U.S. so it could secure exclusive access to any potential COVID-19 vaccine the firm might develop. While the Trump administration and the company deny that any offer was ever made, the reports prompted major concern and furious reactions in several European countries.

France, Germany and other European countries initially prevented medical supplies from being sent to their EU neighbors. They have since reversed those policies, due to their negative effect on European supply chains. The damage to EU solidarity, however, has been done.

Moreover, the “just-in-time” global supply chains that companies have built contain serious vulnerabilities. Firms have reduced or eliminated excess capacity for short-term profits, cost optimization and supply-chain efficiency. The gains, however, have come at a cost: supply security, diversification, redundancy (having back-up systems and excess capacity), resilience (the speed with which functionality can be restored) and long-term stability have all been sacrificed.

By ignoring geopolitical risk management strategies, firms have not made their global supply chains flexible enough to substitute one supplier or component for another. It is now clear that the global health sector is too dependent on a handful of countries – China and India in particular – as major providers.

Facts & figures

China’s domination of healthcare supply chains

China manufactures half of the world’s medical masks. Its production was some 200 million masks a day by the end of February 2020 – still not enough to keep up with global demand. It also produces 80% of the ingredients in antibiotics used worldwide. Together, China and India supply 90% of the world’s active pharmaceutical ingredients and chemical raw materials for generic medicines.

In March, India, the world’s largest exporter of generic drugs, put restrictions on the export of some medicines. In April, it slapped an outright ban on the export of antimalarial drug hydroxychloroquine, which the Trump administration had touted as a potential “game changer” in the fight against COVID-19. It has since relaxed that ban along with other restrictions, but some remain in place.

Impact on the energy sector

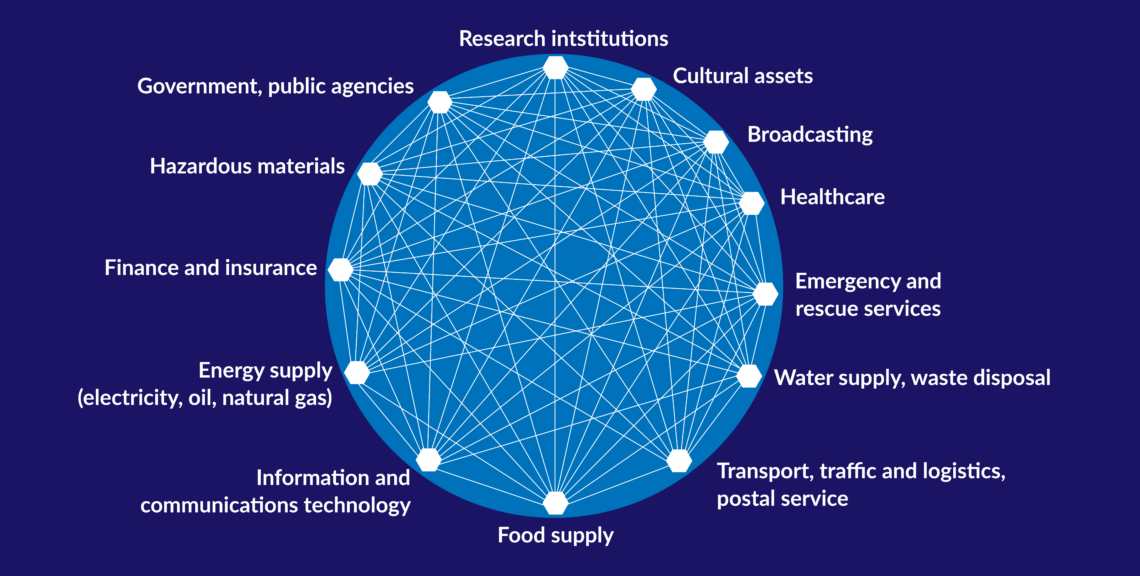

The longer the pandemic lasts, the bigger the effect on other critical infrastructure – including the energy sector – it will have. In the short term, the impact will be twofold.

First, it could affect the reliability of electricity supplies, without which the healthcare sector and other crucial systems cannot function. All modern societies rely on a stable supply of electricity. Maintaining a reliable national electricity supply and grid stability could therefore become a critical task in the coming months. However, countries whose electricity is increasingly generated by intermittent renewable sources will struggle to guarantee a consistent supply. Increasing cyberattacks on electricity grids and generation systems further complicate providing a stable supply of electricity.

Second, it could affect staffing in the energy sector. If the pandemic lasts long enough to significantly reduce the highly skilled workforce, supply chains may be compromised. This could have cascading effects on critical energy infrastructure. German and U.S. power plants have already introduced emergency measures, reducing staff and having some workers live temporarily on-site.

Facts & figures

The problem is particularly worrying when it comes to nuclear power. In the U.S., workers, suppliers and vendors still have access to nuclear power plants, and the government has relaxed regulations, allowing for longer shifts. However, certain operations are limited. Almost all of the nuclear fuel exchanges scheduled for 2020 will have to be postponed.

Clearly, the existing emergency plans for critical infrastructure need to be reviewed. Even longer-lasting social distancing rules could complicate how such facilities function.

Supply-chain renationalization

At the same time, a major reevaluation of the vulnerabilities and shortcomings of global supply chains will have to take place. A return to a world that indiscriminately embraces globalization appears to be an unrealistic scenario.

When the pandemic broke out in the Chinese region of Wuhan, Beijing began to buy up and hoard medical masks and other equipment, importing large quantities from around the world. Although the move was an understandable reaction from China, it contributed to the lack of medical supplies throughout Europe.

The EU and its member states initially failed to coordinate their response to the outbreak, leaving several European countries to fend for themselves. When Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel gave an emergency address to her population on March 18, she did not mention the EU once.

A renationalization of public services and critical supply chains seems inevitable.

A renationalization of public services and critical supply chains therefore seems inevitable. Since no government can accept such helplessness in the face of another pandemic, we can expect countries will want more control over medical supply chains.

European politicians – both at the member state and EU levels – have already begun calling for more medical manufacturing capacity and storage space for equipment and pharmaceutical ingredients. For one country to do so on its own, however, would be insufficient and too costly. Ultimately, it would be impossible to decouple such facilities from European and global supply chains.

Moreover, a complete renationalization of services like healthcare or energy provision could undermine the EU’s internal market. Member states have already flouted internal market rules and the bloc’s core principle of solidarity with their initial responses to the pandemic. The closing of national borders has hindered urgent deliveries of medical supplies within the EU.

The energy sector’s lessons

The lessons Europe learned from previous energy crises could prove helpful. The 1973 global oil crisis, as well as gas-supply crises in 2006, 2010 and 2014, led to a painful realization about energy-supply security: it is a public good that cannot be left to the industry and global markets. The issue has since become an important topic on the EU’s agenda.

Facts & figures

Ways countries can enhance energy-supply security:

- Building up oil and gas storage sites, giving them a stable supply when import shortages or disruptions occur. For oil, the reserve usually equals 90 days of national demand

- Diversifying the energy mix by expanding renewable energy

- Diversifying oil and (particularly) gas imports to reduce dependence on a single supplier (such as Gazprom)

- Protecting critical energy infrastructure in the face of rising cybersecurity challenges

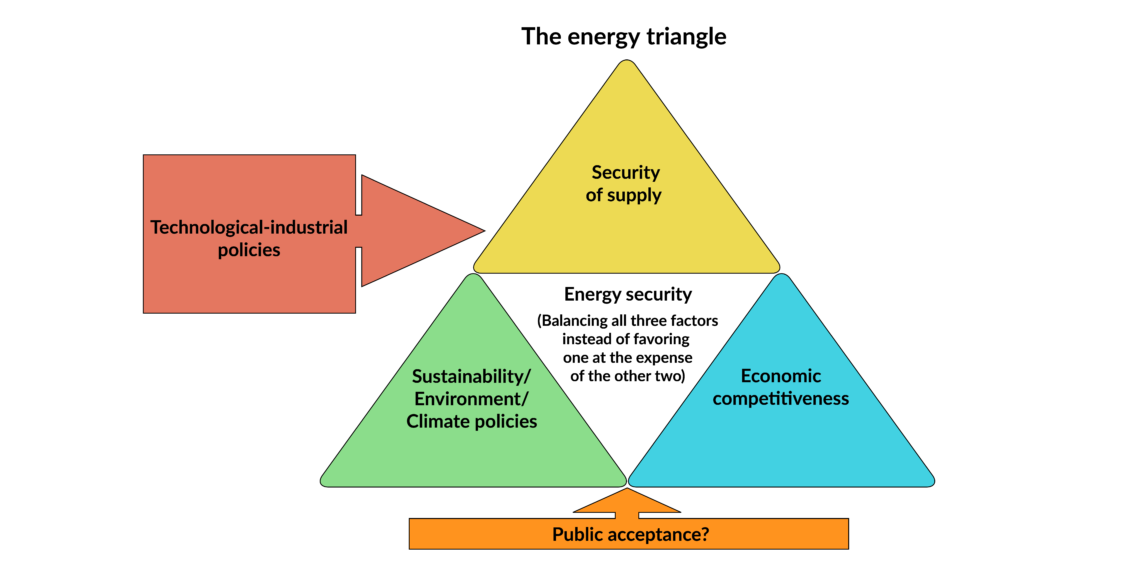

The EU’s energy policies have often been framed in terms of the so-called “energy triangle” (see above), in which governments must balance energy-supply security with economic competitiveness and environmental protection. Though attempts at doing so have brought policy conflicts, the strategy offers useful takeaways for Europe’s healthcare sector.

The European energy sector is in a much better situation than its healthcare sector when it comes to supply security. Its imports and supply chains are much more diversified, redundant and resilient.

In 2017, the EU launched a “Battery Alliance” initiative to build 26 factories for manufacturing electric vehicle (EV) batteries. Currently, global battery production is dominated by China, South Korea and Japan, and the initiative aims to strengthen Europe’s industrial sector, preserve its global competitiveness and enhance energy security. In this case, the EU has recognized the need to avoid overdependence on new global supply chains dominated or strategically controlled by a single provider, such as China.

Scenarios

COVID-19 has exposed many vulnerabilities in complex global supply chains, including an overreliance on single-source providers – which are often not transparent in their operations. Governments and companies are unable to control them to better manage supply-chain risk. Both the public and private sectors tend to adopt reactive rather than proactive approaches to sudden supply-chain disruptions. As a result, they are often insufficiently prepared.

The blame for Europe’s initial failure to cooperate and coordinate does not lie with EU institutions, but rather with national governments. The EU is only as strong as its member states make it. Only enhanced global and European cooperation can contain the spread of the global COVID-19 pandemic.

Once the crisis subsides, the most likely scenario is neither a full restoration of the highly interconnected globalized world, nor uncontrolled nationalism. In addition to countries taking control of medical supply chains, the EU will have to find new ways to maintain the benefits of globalization (thanks to which so many member states’ economies have prospered) while guaranteeing supply-chain security.

Doing so would include creating storage capacity and rebuilding medical equipment production in Europe, as well as diversifying EU imports. However, focusing on import diversification alone, as many commentators recommend, is insufficient to guarantee supply security and resilience, due to inherent systemic shortcomings within global supply chains.

Strengthening national resilience to potential crises in an open economy does not have to conflict with the interdependence that comes with global supply chains; they can complement each other to better tackle global challenges.