Joseph Kabila will not be moved

For long-serving presidents in sub-Saharan Africa, there are few incentives to step down. That applies to President Joseph Kabila in the Democratic Republic of Congo, who has managed to extend his term beyond the constitutional limits.

In a nutshell

- DRC President Kabila shows no sign of honoring a 2016 deal with the opposition

- Lacking strong leadership, the opposition may be too divided to topple Mr. Kabila

- Violence is spreading, and armed groups are expanding in the DRC’s mineral-rich East

Joseph Kabila’s rise to power followed a common script in African politics: he is the son and successor of the Democratic Republic of Congo’s first president, Laurent Kabila (1997-2001), the man who led the rebellion against Mobutu Sese Seko’s dictatorial regime. Now in his 17th year in office, the 46-year-old president has joined the list of Africa’s long-serving leaders.

As a head of state, Mr. Kabila’s record is mixed. He was responsible for the relatively successful 2002 peace deal that ended the Second Congo War and it was under his tenure that the DRC held its first multiparty elections in 2006, the year a new constitution was approved. These are considerable achievements, especially if we consider that from the pre-colonial kingdoms to Belgian King Leopold II’s Congo Free State or Mobutu’s Zaire, the country’s default mode has been despotism or civil war.

Although the DRC’s development indicators remain below the African average, there has been significant progress over the past decade, with increases in life expectancy and school enrollment and a dramatic fall in childhood mortality. Economic indicators also improved under Joseph Kabila’s rule, although they remain far below the country’s potential.

Despite some years of fast economic growth driven by a combination of commodities exports and stabilization efforts, the DRC under President Kabila remains an authoritarian and aid-dependent country. Six out of seven Congolese live on less than $1.25 a day. The economy has been decelerating since 2015, as global commodity prices have slumped, the inflation rate has risen, and regional violence has worsened the prevailing political instability.

Playing for time

Back in 2015, a year before the end of his second term, President Kabila revealed his intention to remain in power beyond 2016. However, according to the 2006 constitution, Mr. Kabila was expressly prohibited from running for a third term. Faced with the same dilemma, the leaders of Rwanda and Burundi managed to secure legal sanction for extending their term limits. But Joseph Kabila found it more difficult to tinker with the DRC’s constitution.

Rwandan President Paul Kagame enjoys an unusual “extraconstitutional legitimacy” – based on a combination of his historical achievements, plus the country’s economic growth and stability – that was sufficient to persuade Rwandans to scrap the term limits. The measure easily passed a 2015 constitutional referendum. Burundian President Pierre Nkurunziza, while far less popular than Mr. Kagame, also managed to overstay his legal term – not by changing the constitution, but by securing a favorable interpretation from Burundi’s Constitutional Court.

President Kabila’s only method for staying in power was to delay elections as long as possible.

Lacking Mr. Kagame’s legitimacy and the legal loopholes exploited by Mr. Nkurunziza, President Kabila’s only method for staying in power was to delay elections as long as possible. In May 2016, the Constitutional Court of the DRC ruled that Mr. Kabila would remain in office until elections could be held. However, with no elections in sight, violent protests broke out again in December 2016.

Domestic mobilization and international pressure forced the Kabila government to sign an agreement with a coalition of opposition parties on Dec. 31, 2016. The New Year’s Eve Accords, mediated by the National Episcopal Conference of Congo (CENCO) set the terms for what it called a “political transition”: elections would be held by the end of 2017; Mr. Kabila was to be prevented from running for a third term; and, although he was allowed to stay on until the elections were held, a transitional government would be put in place, including members of the opposition.

However, it soon became clear that the agreement was a dead letter. The transitional government was mainly composed of Mr. Kabila’s political allies and proteges, while the country’s electoral commission announced that financial and logistical difficulties would make it impossible to hold a nationwide poll before the end of 2018.

‘Transition without’

Under increasing pressure, Joseph Kabila appears to be making grudging concessions. According to the DRC government, presidential, legislative, regional and local elections will take place on December 23, 2018. The president has agreed not to seek a third term in office and will announce in July a candidate to represent his People’s Party for Reconstruction and Democracy (PPRD).

However, a lot can change between now and December. Fearing the president will have a change of heart, the leading figures of the opposition believe that the only way to secure free and fair elections would be a “transition without Kabila.”

Facts & figures

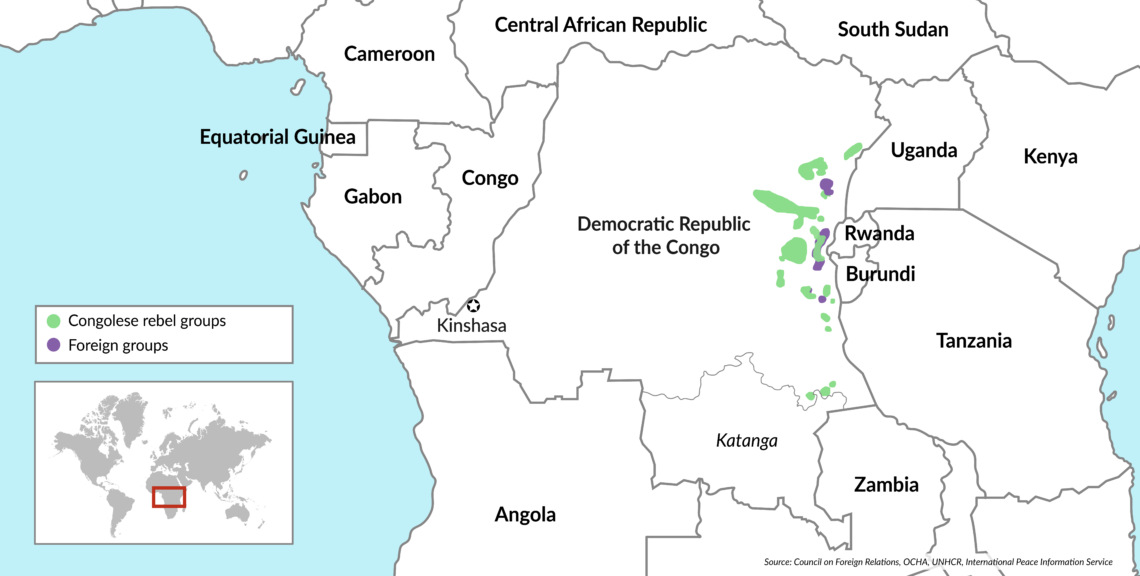

Armed groups in the DRC

They have called for the president’s ouster and the formation of an interim government with representatives of the ruling coalition, the opposition and civil society.

While this proposal seems reasonable, it is virtually unworkable under a semi-authoritarian regime that concentrates power in the hands of the president. Unless Joseph Kabila is removed from his post, he will retain an enormous advantage throughout 2018 and may even be able to buy extra time.

The logistical and legal obstacles cited by the constitutional court are no longer a valid reason for delay (the National Electoral Commission has made significant progress in registering 46 million Congolese voters, devising a voting system and getting an electoral law passed), but Mr. Kabila can always cite the deteriorating security situation. If political and ethnic violence persists in key regions of the country, including Kinshasa, Eastern Congo and Kasai Central, he may be able to argue that conditions are not suitable for free and fair elections.

Polarized opposition

With a population of 78 million divided into four major and more than 250 smaller ethnic groups, the DRC is sub-Saharan Africa’s largest country by area. Political power in this vast territory is fragmented and polarized, reflecting two different realities. Kinshasa is the center of the country’s political, representative and “soft” power, and the stronghold of the urban opposition to President Kabila’s rule. But this opposition is splintered among the 98 political parties in the National Assembly, 45 of which have only one representative.

At the national level, the main threat to Joseph Kabila’s ambitions is the Rassemblement coalition, which groups several of the largest opposition parties. However, the death in February 2017 of Mr. Kabila’s old rival, Etienne Tshisekedi, left a leadership void that remains to be filled. With the opposition focused on a “transition without Kabila,” it must decide soon on a strategy for the 2018 presidential elections. Assuming a joint candidate can be agreed upon, the most likely possibilities are Felix Tshisekedi and Moise Katumbi.

Moise Katumbi is a former Kabila man who has made himself into one of the DRC’s most popular politicians.

Felix Tshisekedi – like Joseph Kabila – inherited his father’s position as leader of the Rassemblement opposition coalition. Although he has taken a leading role in the mass protests against President Kabila, his lack of political experience is seen by many in the opposition as a major weakness.

Moise Katumbi, by contrast, has had ample opportunity to demonstrate his political skills. He was once a Kabila man, serving as governor of resource-rich Katanga province (the president’s home region) in 2007-2015 and increasing his considerable family fortune in the mining and logistics sectors. In 2015, after publicly challenging President Kabila, he resigned his governor’s post and left the ruling PPRD. He has since made himself into one of the DRC’s most popular politicians. In 2016, Mr. Katumbi was forced to flee the country after a warrant was issued for his arrest. However, he is expected to return from exile soon and formally announce his presidential candidacy, which looks poised to pick up considerable support.

Another foe of President Kabila’s has been the Roman Catholic Church. The DRC is Africa’s largest Catholic country, and the local church hierarchy has played an important role not only in mediating the conflict, but also in organizing street protests against the regime.

Spreading violence

Outside Kinshasa, however, power is more likely to come from the barrel of a gun than from the pulpit or ballot box. Armed groups rather than parties exert the most political clout. The DRC’s astonishing proliferation of rebel and armed groups reflects the difficulties of a dysfunctional state trying to operate over a vast and ethnically diverse territory, with poor transport and communication links. It is also a legacy of the Third Congo War (2006-2013).

In the country’s eastern provinces, for example, an estimated 120 different armed groups are active, including the National People’s Coalition for the Sovereignty of Congo (CNSPC). This group, led by William Yakutumba, operates in South Kivu and has clashed with army forces repeatedly in recent months. The CNSPC is expanding its territory along Lake Tanganyika and declares its goal is to march on Kinshasa and overthrow President Kabila. Although the group lacks the means to occupy the capital, it certainly has the power to worsen security conditions in eastern Congo. The Congolese armed forces, numbering about 150,000 troops (many of them former rebels), lack the logistics, resources, and command and control capabilities to put down this type of insurgency.

Perhaps the best hope of heading off a violent outbreak is intervention by MONUSCO – the United Nations’ largest peacekeeping mission with more than 18,000 troops (including both military and police forces) and an annual budget of $1.14 billion. However, on the ground, MONUSCO has been virtually powerless. Last year, two UN experts were murdered in Kasai Province and 15 peacekeepers were killed in North Kivu by a Ugandan rebel group – the Allied Democratic Forces. The spreading violence led the UN to declare a level three emergency in October, when the number of displaced people in the DRC reached 4.1 million. The UN has recently warned that a “humanitarian disaster of extraordinary proportions” is about to hit the country`s southeastern region.

Resource curse

The number of rebel groups operating in the DRC is also a function of the country’s abundant natural resources. Besides vast areas of fertile farmland, the DRC is extremely rich in minerals. It is Africa’s top producer of copper, tin and cobalt. According to a 2013 United States Geological Survey report, the DRC supplies 48 percent of the world’s cobalt and accounts for 47 percent of global reserves. The mineral is used as an essential component in batteries and cell phones and a key element in the coming electric mobility revolution.

In 2017, the price of cobalt soared 129 percent, to $75,500 per ton. Global demand for the metal is set to increase during the next years, although it is expected to decline later as cheaper and more efficient alternative technologies are developed. The surging demand has prompted heavy investment inflows into the DRC, specifically in the mining sector. But this may not necessarily do much to improve the country’s overall economic performance or average living conditions. According to Global Witness, only 6 percent of the country’s mining export income ever reaches the national budget.

President Kabila may stretch his term beyond 2018 by militarizing politics and increasing state-supported violence against civilians.

The DRC Government has recently approved new legislation that includes a 3 percent tax increase on cobalt exports. While this hike may deter investors – who may look to other cobalt-rich regions such as Canada, Russia or Scandinavia – there is no guarantee it will increase tax revenue or that the proceeds will be reinvested in the economy and used for the benefit of the Congolese population.

Scenarios

2018 is expected to be a tumultuous year for the DRC. Even if elections take place in December, they will hardly represent the beginning of a democratic transition. President Kabila, the opposition coalition and some of the armed groups operating in the eastern part of the country will be the key players shaping the country’s destiny.

Two scenarios seem plausible.

The most likely is that President Kabila succeeds in stretching his term beyond 2018. He would achieve this goal by “militarizing” politics. This would involve obtaining the tacit consent of the Constitutional Court and the National Electoral Commission and normalizing the use of force. Repression and state-supported violence against civilians would increase, as would popular protests against Mr. Kabila. But the latter would remain concentrated in urban areas. Instability would discourage foreign investment and contribute to further deterioration of the economy.

This deepening crisis would give Mr. Kabila further justification for postponing elections (beyond his real concern for his personal safety and preservation of his vast fortune). If delay proves impossible, he may foment violence throughout the country as a last resort. While no rebel group appears strong enough to overthrow Mr. Kabila, large sections of the country may descend into chaos and the humanitarian situation could become intolerable.

A more optimistic but still plausible scenario would see the DRC opposition emerge victorious. This assumes that even as violence increases, the main confrontation between Mr. Kabila and his opponents is played out at the political level, and that armed rebels do not extend their operational reach. The opposition would be united behind a single candidate, creating a viable alternative and reassuring the international community. Under this scenario, international pressure would also act as a curb on the president’s ambitions. As Mr. Kabila becomes more isolated, his highly effective patronage networks would become compromised. That could ultimately force him to name a presidential candidate from the ruling party and negotiate terms for a safe exit for himself and his family.