Changing migration trends in Russia

Russia could soon face additional demographic problems due to new migration trends. The instability of the ruble is discouraging many migrants from former Soviet states, who opt for countries with higher living standards instead – meaning the low-skilled labor shortage could soon worsen.

In a nutshell

- Russia relies heavily on migrant labor

- There could soon be a shortage of foreign workers

- The situation will worsen unless the economy improves

As of 2020, Russia has the fourth-largest migrant population in the world, after the United States, Germany and Saudi Arabia – some 12 million people in total.

Russia attracts large numbers of migrants from the former republics of the Soviet Union, where the standard of living is often significantly lower than in Russia. This creates powerful, primarily economic, incentives for migration. Moreover, Russia has a visa-free border-crossing regime with these countries, with the exception of the Baltic states and Georgia.

This population is made up of two distinct segments: migrants who seek to obtain Russian citizenship, and temporary labor migrants.

Post-Soviet populations flow

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, as part of the population exchange between the former Soviet republics between 1991 and 2000, 6.9 million people (mostly Russian speaking) moved into Russia, and 3.1 million left.

In the 2000s, this flow became smaller. Between 2001 and 2010, some 2 million people arrived in Russia, and 700,000 left. By then, most of the Russian-speaking population living in former republics had already returned. As for the countries that were not part of the Soviet Union, emigration from them to Russia was and remains insignificant.

The Russian labor market is experiencing a chronic shortage of low-skilled labor.

However, in the 2010s, migration flows to Russia increased again, with 5.5 million people arriving in 2011-2020, and 3.1 million leaving. This was due to more labor migrants arriving in Russia, primarily from Central Asian countries like Kyrgyzstan,Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, as well as Armenia, Azerbaijan and Ukraine. Some stayed and became permanent residents. There was also a significant influx of migrants from Ukraine in connection with the events of 2014 in the Donbas: 1.1 million people.

Demographic measures

In 2006, to improve the demographic situation Russia adopted a program “to assist the voluntary resettlement of compatriots living abroad to the Russian Federation.” The Russian government defines compatriots as persons demonstrating “commonality of language, history, cultural heritage, traditions and customs [with the Russian state] and their direct relatives,” persons “living beyond the borders of the Russian Federation having…spiritual, cultural, and legal connections with (Russia),” or “persons whose direct relatives lived on the territory of the Russian Federation or the Soviet Union.”

These provisions therefore include people residing in former Soviet states, both citizens of these countries and those without citizenship. It also takes into account emigrants from the Russian Federation and the Soviet Union who lost their citizenship and became stateless persons or citizens of a foreign state.

Under the program, these migrants are provided with benefits, but on the condition that they move to Siberia and the Far East. According to official data, thanks to this program, 826,000 people returned to Russia between 2007 and 2019, mostly from former Soviet republics.

The newcomers compensated for the natural decline of the population, and the number of permanent residents increased until 2017. However, from 2018 to 2020, it became insufficient to compensate for the aging of the Russian population.

Emigration

There is also an outflow of population from Russia. At the end of the Soviet period and in the 1990s, it was primarily the ethnic Jews and Germans. However, the number of people leaving Russia, even at the height of the trend, was demographically insignificant. For example, in 1999, Jewish emigration from Russia amounted to 20,000 people, and then fell sharply to about 1,000 people a year.

It is also worth noting that obtaining Israeli citizenship does not always mean that a person actually moves to live in Israel. In recent years, the practice of obtaining second citizenship – to travel more easily or to receive medical services – has become more common.

The situation is similar with ethnic Germans emigrating from Russia. After peaking in the late 1990s (at about 50,000 people per year), there was a sharp drop to 4,000-5,000 people annually.

However, when it comes to overall emigration, there was a sharp increase in numbers in the 1990s.

Later in the 2000s, this flow became minimal, primarily due to the rapid economic recovery and a significant increase in the living standards of almost all socioeconomic groups. But with the economic stagnation of the 2010s and the gradual decline in real income for the majority of the population, emigration from Russia increased more than tenfold over the last decade.

In fact, emigration from Russia is now much greater than official statistics show: only those who unregistered from their place of residence before leaving the country are counted as gone. To leave Russia, is enough to get an entry work visa or become an investor who applies for citizenship. For the most part, these are highly educated and skilled people. In particular, it is estimated that 200,000 scientists leave Russia every year. It is widely believed that the real volume of emigration is three to four times higher than shown by official data.

Many in Russia want to emigrate. Surveys conducted by the independent sociological agency Levada-Center note a gradual increase in the wish to emigrate among people aged 18-24 years, on the rise since 2014. In September 2019, more than half of the respondents (53 percent) of this age group expressed a desire to move abroad permanently. The trend is also visible among the middle-aged population, although to a lesser extent.

Answering the question “What makes you want to leave your country most of all?” people most often answered: a desire to provide their children with a decent future abroad; poor economic conditions in Russia; better medical services abroad; and the political situation in Russia.

Facts & figures

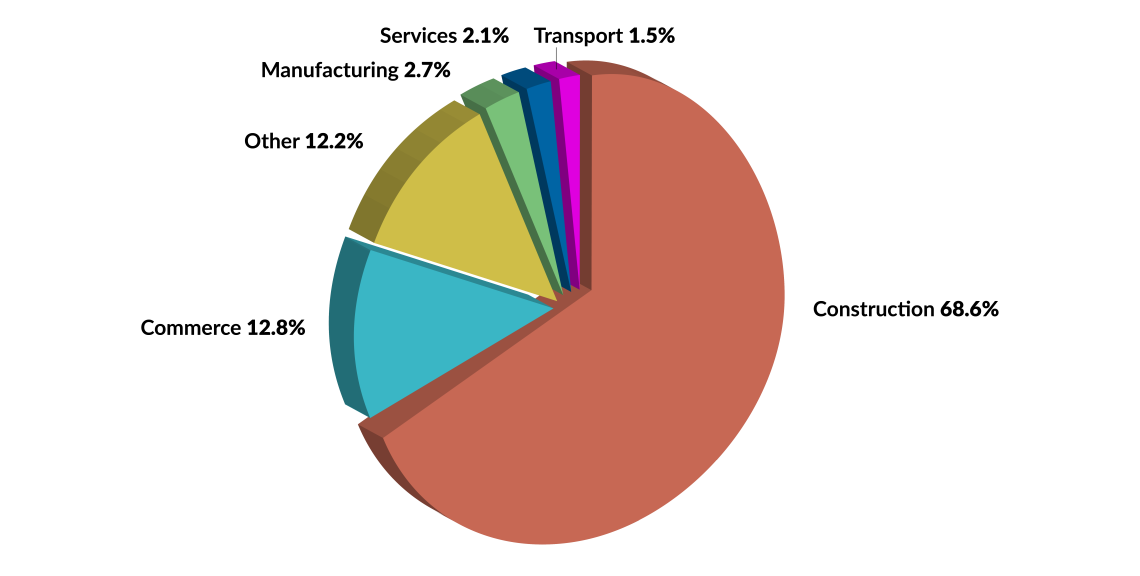

Employment sector of migrants to Russia, 2019

Migrant workers

The Russian labor market is experiencing a chronic shortage of low-skilled labor. This problem has been solved in recent years by migrant workers – that is, people, most of whom come to Russia on a temporary basis.

It is difficult to determine exactly how many labor migrants are in Russia since they enter the country without a visa. It is therefore unsurprising that official data varies wildly. The numbers of the Russian Statistical Service for 2019 were six times lower than those of the Federal Security Service: 4.9 and 32.6 million people respectively.

Where do temporary labor migrants come to Russia from? Before the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, when the borders between Russia and most of the post-Soviet states were practically open, they mostly arrived from Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Armenia and Belarus.

Temporary labor migrants send most of their income to the countries where they permanently reside. Remittances in post-Soviet states amount to several hundred million dollars per month.

Emigration from Russia is much greater than what official statistics show.

To work legally in Russian territory, a migrant from a post-Soviet country with which there is a visa-free regime only has to buy a work permit after crossing the border. The cost of such yearly permits varies by region. In the city of Moscow, where the largest number of temporary labor migrants is concentrated, it is about $72. Only 1.5 million people bought such a permit in 2019 – most of the temporary labor migrants entering Russia from post-Soviet countries work illegally.

In Russia, there is a special system for attracting highly qualified migrants who work, as a rule, in large companies as top managers or specialists. These people mostly come from the U.S. or the EU and receive work visas issued at the request of Russian employers, but their total number is small. As of 2020, there were only 68,000 such foreigners in Russia.

Scenarios

Russia will most likely see a decrease in the influx of people into the country, both for permanent residence and temporary employment.

This is primarily due to the state of the economy, which is unlikely to develop dynamically in the medium term. Migrants from Armenia, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine will prefer to move to Europe and North America, especially since there is a steady need for relatively low-paid labor there.

Migrants from Uzbekistan are increasingly drawn to Kazakhstan’s dynamic development. In addition, given the rapid aging of China’s population and the simultaneous increase in the standard of living of its citizens, the Middle Kingdom may soon become a destination for labor migrants of various skill levels, including workers from Russia.

One of the factors that discourage migrant workers from coming to Russia is the instability of the ruble against major world currencies. From 2014 to 2020, the ruble depreciated against the U.S. dollar by more than 2 times. As a result, the incomes of migrant workers who transfer money to their home country, most often in dollars, have also decreased.

The shortage of low-skilled labor, in turn, further exacerbates the problems of the Russian economy, which is not being restructured in favor of more modern high-tech industries with high labor productivity.

This situation may be aggravated by the accelerating emigration of young, educated Russians to North American and European countries, as well as to Australia and New Zealand.

Russia’s demographic issues have become acute enough to prompt President Vladimir Putin to state that the “problem has acquired a systemic economic character due to the lack of the required number of workers in the labor market. … Our losses are approximately 1.1-1.2 GDP percentage points per year. For humanitarian reasons, and in terms of strengthening our statehood, and for economic reasons, the demographic problem should be addressed as a major issue to be solved.”

In the coming years, we should expect inconsistent attempts to liberalize migration policy, meaning the removal of remaining barriers to the entry of migrants into Russia, both for permanent residence and temporary work. But these measures will meet resistance from both a part of the state apparatus and public opinion.

While Deputy Chairman of the Russian government Marat Khusnullin said it was necessary to attract another 5 million migrants for the needs of the construction sector, Moscow Mayor Sergei Sobyanin believes that fewer migrants and more Russians should work in this field. He also stated that it is necessary to reduce the number of migrants in the housing and communal sector.

This discussion is taking place against a backdrop of fairly broad xenophobic sentiments in Russian society. Opinion polls show that only 28 percent have a positive attitude toward the influx of foreigners into various sectors of the economy. Meanwhile, 41 percent of citizens have an unfavorable view of such migrants. To the question “Should Russia restrict immigration from Central Asia and the Caucasus,” one-third answered positively.

Therefore, even modest efforts to change migration policy are unlikely to have the expected effect. To be addressed adequately, this strategic challenge would require radical changes in both domestic and foreign policy, so as to make Russia open and attractive as an investment destination and a country of residence.