Russian arms exports in a tailspin

The Kremlin’s war on Ukraine has weakened Russia’s standing as a global arms exporter, with a market share that will likely continue to shrink.

In a nutshell

- Russia’s top customer, India, is shifting to Western weapons

- Clients are disappointed in the quality and reliability of Russian arms

- Only China and Egypt increased their arms purchases from Russia

Russia’s war on Ukraine is wreaking havoc on the prospects for future Russian arms exports. The implications go beyond lost revenue. Since the export of arms has long been a core tool of the Kremlin’s foreign policy, a weakened presence in the global arms market undermines Russia’s geopolitical role.

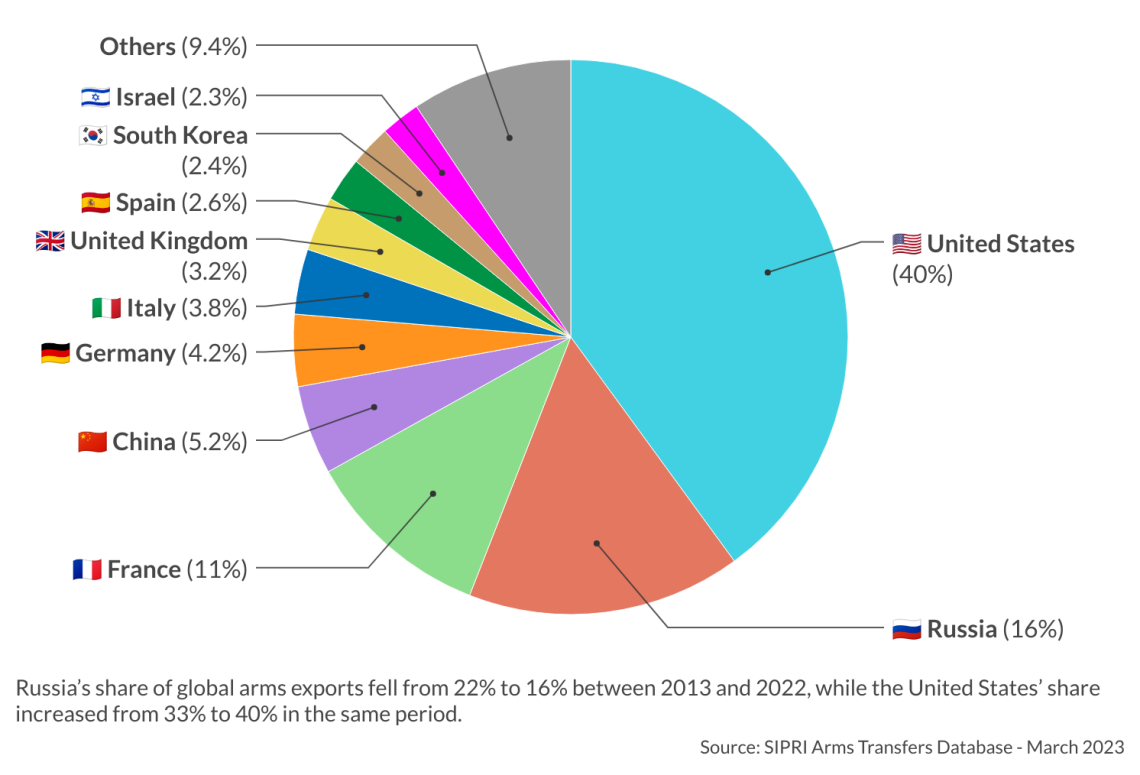

According to data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), Russia’s share of global arms exports fell from 22 percent from 2013-17 to 16 percent from 2018-22. Meanwhile, the United States cemented its position as the global leader, increasing its share from 33 to 40 percent.

While these numbers present a clear downward trend for Russian arms exports over the decade preceding the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, they hardly scratch the consequences of that aggression. When numbers are published for 2023-2027, they will likely show an outright tailspin.

Big decline among some top customers

A closer look at the SIPRI numbers provides important insights into how the Russian export market is being transformed. For eight of its 10 largest customers, Russian arms sales declined and, in some cases, the decline was catastrophic. The biggest news item was that sales to India, long the largest recipient of Russian weapons, dropped by 37 percent. Sales to the other seven fell by an average of 59 percent.

China (up 39 percent) and Egypt (up 44 percent) were the only countries that increased their purchases of Russian arms. That was enough to move the two nations to second and third, respectively, in destinations for Russian arms exports after India.

Recent months have brought a spate of important news suggesting how foreign markets for Russian arms may continue developing. The downside may be divided into three cases reflecting three different dimensions of Russia losing out.

More by Stefan Hedlund

The problem-ridden development of a Russia-Iran axis

Kazakhstan helps Russia evade Western sanctions

Georgia’s divide between Russia and the West

No. 1 customer India starts to look elsewhere

The first is India, which has gained notoriety as the only significant democracy not to take a stand against the Russian aggression. Like China, it has pounced on the opportunity to import large quantities of Russian oil at a heavy discount. While the leading Western powers have taken a dim view of these activities, India is also turning away from Russia as its primary arms supplier. In the longer term, this is more important.

Between the two periods measured by SIPRI, Russia’s share of Indian arms imports fell from 62 to 45 percent. That was a significant development because India remained the world’s largest arms importer. And it was not much of a surprise. The Indian experience of defense cooperation with Russia is not good. Its decision to purchase an old Russian aircraft carrier has been described as a “train wreck,” as contractors failed to complete the refurbishment. And its interest in continued purchases of Russian submarines was doused in 2013, when a Russian-built sub exploded and sank in Mumbai, killing 18 crew members.

In mid-June this year, it was announced that India was contracting with German Thyssen-Krupp for six new submarines. And in mid-July, in advance of a visit by Prime Minister Narendra Modi to Paris, it became official that it is looking at purchases that include three Scorpene-class submarines and 26 Dassault Rafale fighter jets.

The more likely scenario is that Russia is defeated in Ukraine and remains under sanctions for an extended period.

Iran seeks technology for arms

A second telling case is Iran, which supplies Russia with Shaheed attack drones for use against Ukraine. Rumors have it that Iran also considered supplying Russia with ballistic missiles in return for advanced Russian fighter jets. Under a deal signed with former Iranian President Hassan Rouhani, Moscow has agreed to provide 50 Su-35 fighter jets. But Iran is not expecting delivery any time soon. Brigadier General Vahedi, the commander of the Iranian Air Force, admitted he did not know when the Russian jets would arrive in his squadrons.

Serbian leader prefers France for some weapons

A third politically important case is Serbia, long considered Russia’s friend and staunch ally. In mid-April of 2023, President Aleksandar Vucic said his country planned to purchase 12 new Dassault Rafale jets from France, and possibly an additional dozen used planes from another Western country. This was not the first instance of Serbia preferring France over Russia. In 2016, it bought helicopters from Airbus and in 2019, it acquired Mistral surface-to-air missiles. These developments indicate that Belgrade may be moving away from its traditional friend and arms purveyor.

These three cases illustrate how geopolitical trends are working against Russia. In the critical case of India, mounting frustration over sloth and incompetence in Russian arms deliveries is combined with concern over the ongoing transformation of the security architecture in the Indo-Pacific. As the major Western powers are building alliances to counter China, India has reason to question the wisdom of being aligned with Russia, which is becoming more dependent on China.

The case of Iran shows how the Middle East’s complex security situation presents Russia with some tough choices. It needs good relations with Tehran, but if it were to supply advanced weapons like the Su-35, it would have to expect a severe response from Israel, which thus far has kept a low profile in supporting Ukraine. That would be terrible news for Moscow.

The case of Serbia, finally, shows how the lure of membership in the European Union also undermines Russian clout in the Balkans. Despite its long tradition of “Slavic brotherhood” with Russia, Belgrade is now a candidate to join the 27-nation EU and is under pressure to scale back its links to Moscow. Although President Vucic has lingering sympathies for Russia, he is not only increasing weapons purchases from the West: he has joined Western powers at the United Nations in condemning Russian aggression against Ukraine.

That leaves the more profound question of whether countries like China and Egypt will remain good customers. The answer hinges on demand and supply, precisely whether Russian arms producers can deliver.

Any present assessment of the future role of Russia in the global arms trade depends on the outcome of the war in Ukraine. In the short term, Moscow will find appearing as a reliable supplier challenging. The biennial MAKS air show planned for July this year in Russia had to be canceled. Aside from the entertainment value, the MAKS has a long tradition as an essential venue for Russian arms makers to showcase their wares and sign contracts. This year, they had little to show and no expectations for serious business coming their way.

Long-term supply problems for Russia

For years to come, Russia will be focused on rebuilding its military forces, which will be an uphill struggle. In addition to the ongoing destruction of equipment on Ukraine’s battlefields, the stock of available equipment is steadily degraded by the need to cannibalize some to secure parts for others. Russian aviation is suffering very badly from this. Sanctions busting has helped ensure a flow of microprocessors that allows arms producers to maintain some output. However, that has mainly been done by modernizing old equipment long held in storage, often outdoors. It is hardly helpful to exports.

A significant obstacle in rebuilding military-industrial capabilities is that critical suppliers of military technology were located in presently unfriendly countries. The most important is Ukraine, which was the source not only of vital inputs like helicopter engines and naval diesel turbines. It was also home to the maker of the SS-18 intercontinental ballistic missile, the mainstay of the Russian ground-based nuclear deterrent. As relations with the manufacturer in Dnipro have now been severed, it is presently doubtful if the current stock of armed missiles deployed in silos is even being maintained.

Concern over the shrinking number of operational Su-25 ground attack aircraft is heightened by the fact that the main production facility was a factory in Georgia, which Russia bombed during the war in 2008. It ceased operating in 2010, and production inside Russia stopped in 2017.

In theory, these problems may be overcome, but they will require import substitution in practice, highlighting questions of domestic manufacturing performance. Corruption and nepotism are undermining the quality even of crucial weapons systems. A case in point is the Bulava missile developed for the new Borei class of nuclear submarines. Its performance is so erratic that it is said to be a graver threat to the Russian navy than its U.S. adversary.

Vladimir Putin’s not-so-invincible weapons

Before the full-scale invasion, Russian President Vladimir Putin made constant reference to new wonder weapons, like the Avangard hypersonic glide vehicle, the 9M730 Burevestnik nuclear-powered cruise missile, the 3M22 Zircon scramjet-powered hypersonic anti-ship cruise missile, the Kh-47M2 Kinzhal hypersonic air-launched ballistic missile and the Poseidon very long range, nuclear-armed “doomsday” torpedo. The Russian leader was especially fond of touting the hypersonic missiles as invincible weapons that no American air defense could counter.

As it turned out, one Ukrainian Patriot battery managed to defeat an incoming volley of no less than six Kinzhal missiles headed for Kyiv. While the maker of the Patriot system, the Raytheon Company, is now looking at a rise in demand, the maker of the Kinzhal missile may not find the same enthusiasm for its product.

The performance of Russian high-precision weapons used against Ukraine has been lacking. The kill ratio of incoming missiles has been devastatingly high, and those that have managed to penetrate Western-made air defenses have had limited impact on high-value military targets. As a result, the Russian high command has focused on hitting soft civilian targets. That is not a convincing sales argument for countries that anticipate having to go to war against opponents with Western arms suppliers.

The conclusion is that few if any, countries that have been allowed access to Western arms are willing to purchase from Russia. India has been a notable exception, but that may now be coming to an end. Looking beyond the war in Ukraine, two very different scenarios emerge.

Scenarios

If Russia manages to come out of the war with a negotiated solution and an easing of sanctions, the country may start shoring up its alliances and rebuilding its military industries. That would mean its continued cooperation with China and a focus on developing markets in countries that sided with Moscow during the war. But even in this case, the outlook will be grim.

The rapid rise of Egypt as a market was broken during 2021-2022 when it took no deliveries of Russian arms. In early 2022, Cairo canceled a large order for advanced Su-35 combat jets. Algeria and Indonesia did the same. Even more important is that the volume of Russian deliveries to China in 2020-2022 was much lower than in 2018-2019. Persuading these core markets that Russia may again be trusted will be a hard sell.

The alternative and more likely scenario is that Russia is defeated in Ukraine and remains under sanctions for an extended period. Although sanctions busting may prove helpful in rebuilding the Russian armed forces, it will be at a low technological level that is unattractive for export. Most importantly, China may phase out Russia altogether as it ramps up its domestic production of advanced weaponry and uses reverse engineering of Russian weapons to push the Kremlin out of other markets.