The fate of the Russian Far East takes on greater urgency

Moscow’s dependence on China has deepened because of its war on Ukraine while Beijing is interested in ensuring the survival of the Russian state.

In a nutshell

- Russia’s war on Ukraine affects the U.S.-China standoff in the Far East

- China benefits from Russian resources and wants to prevent its defeat

- Scenarios include success, collapse or weakening of the Russian state

The outcome of Russia’s war on Ukraine will not only affect the security situation in Europe. At the far eastern end of the Russian Federation, it will also influence the geopolitical standoff between China and the United States. As the conflict over Taiwan’s situation intensifies, the question of who controls the Russian Far East will come into sharper focus. The reason is a combination of access to resources for the Chinese economy and the presence of the Russian Pacific Fleet.

In February 2012, as part of his campaign to return to the presidency, then Prime Minister Vladimir Putin spoke about “catching Chinese wind” in the sails of the Russian economy. To be competitive in the 21st century, Russia needed to be closer to Asia. In line with this “pivot to Asia,” in September of that year, he hosted the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Summit in Vladivostok.

Over the following decade, the Far East did play an increasingly important role in Sino-Russian relations. Together with Eastern Siberia, it supplied an important share of the resources needed to feed the fast-growing Chinese economy, to the point where some Chinese referred to Russia as the Middle Kingdom’s “northern resource territory.” This designation suggests that the benefits from increased trade have been heavily skewed in favor of the Chinese side.

More by Stefan Hedlund

Russia’s PMC Wagner dies, but its spirit lives on

Russian arms exports in a tailspin

The problem-ridden development of a Russia-Iran axis

Beijing has been happy to sign major contracts on energy supplies originating in Russia’s eastern regions, including a 25-year, $270 billion deal on oil with Russian Rosneft in 2013 and a 30-year, $400 billion deal on the Power of Siberia natural gas pipeline with Gazprom in 2014. Although prices in these contracts are commercial secrets, it is generally believed that hard-nosed bargaining has favored the Middle Kingdom.

Local Russian observers have begun complaining about how Moscow is selling out to Beijing. In the words of Professor Tatyana Zabortseva of the Siberian Institute of Geography, Eastern Siberia has become a “raw materials pantry” for China. In the Irkutsk region, which is home to the giant Kovytka gas field that feeds the Power of Siberia, locals derive no benefit from the gas, being forced to use firewood and coal for heating.

Beyond helping itself to Russian resources at rock-bottom prices, Beijing has little interest in making direct investments in Russian assets. The only exceptions have been projects that cause harmful environmental consequences. Nor has the Russian side been able to add much value to the resources it extracts. This leads to circumstances such as predatory Chinese logging of the Russian forest belt, which results in the export of round timber for processing in China. Russia does not operate a single pulp mill in the region.

Facts & figures

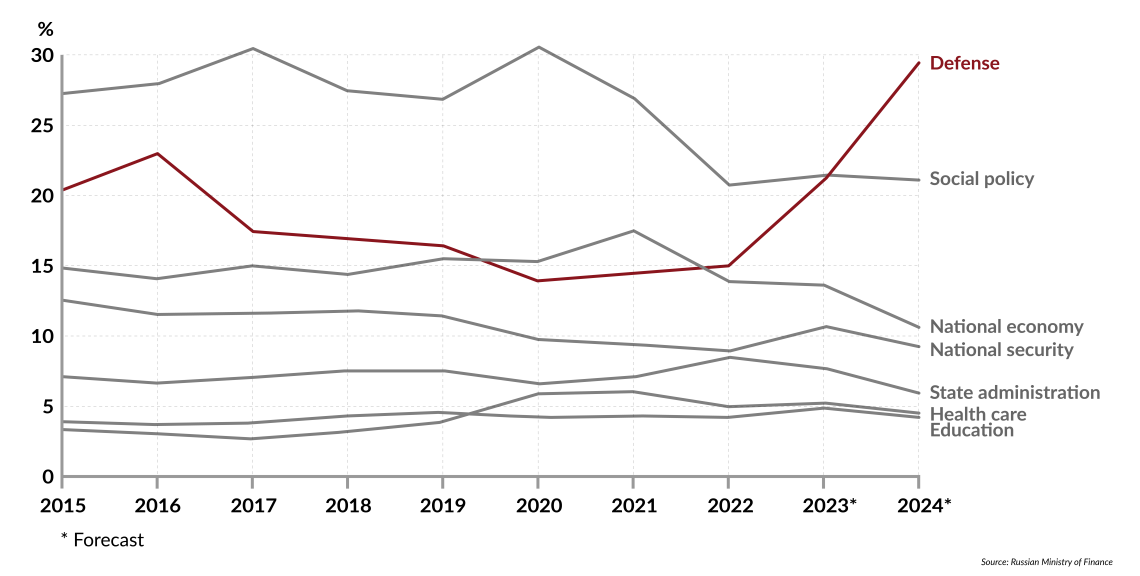

Russia shifts to war economy

Closer military cooperation

Beijing has also welcomed closer cooperation between the Russian Pacific Fleet and the Chinese Navy. Joint naval exercises have been held since 2013. In August this year, a convoy of six Chinese and five Russian warships sailed between Japan’s Okinawa and Miyako islands, proceeding into the East China Sea. Although the ships did not enter Japanese territorial waters, it was the first time that a joint Sino-Russian naval squadron made this passage. The message to the U.S. and its regional allies was loud and clear.

Following its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russia’s dependence on China has deepened. Although surging trade with the Middle Kingdom has made up for lost trade with the West, much of this trade is in Chinese renminbi. The result is a shortage of dollars that translates into a tailspin for the ruble and a spike in inflation. Chinese interest in concluding an agreement on a Power of Siberia II pipeline has been cool, and Russian hopes for open military support have been dashed.

While these developments have proven that there are serious limits to the “unlimited friendship” between the two allies, there are signs that clandestine Chinese support for the Russian military is increasing. A solid victory for Ukraine would remove a major distraction for NATO, allowing the U.S. to focus decisively on China. A collapse of the Russian Federation would bring even worse news, calling into question what role the Russian Far East would play in case of a major confrontation over Taiwan.

Would Beijing be able to count on continued access to critical fuel supplies and on passive or even active support by the Russian Pacific Fleet? The implication is that who will control the Russian Far East is of paramount importance.

Scenarios

Developments may proceed according to three different scenarios, including two unlikely extremes and a more likely middle of the road.

Unlikely scenario: Russia becomes a big North Korea

At one end, Russia emerges out of the war in Ukraine with an outcome it may tout as a win, allowing military planners to start accumulating resources in preparation for a second attempt at conquest and destruction of Ukraine. This scenario has three key elements, all of which are already being called for with some force by hardliners in the security establishment.

First and foremost, the state will be placed under martial law, allowing the Kremlin wide latitude for highly unpopular measures. Second is that borders to the outside world will be closed, allowing mass mobilization of manpower for the armed forces. Third is a return to what was known in Soviet times as “structural militarization,” meaning that the military will have top priority in all matters of resource allocation.

Russia would become increasingly like North Korea, with an outsized priority for the military and draconian powers of repression for internal security services. Foreign investment would come to a halt and the economy would slide into obsolescence, as modern systems start failing. The most striking parallel would be an intensified emphasis on patriotic education for schoolchildren, who would receive military training and be imbued with acrid hatred both for Ukraine and for the West in general.

Although it would remain a nominally sovereign state, Russia would be reduced to the status of a de facto vassal of China. While this would allow Beijing free access to the resources of the Russian Far East, and assurance of support from the Russian Pacific Fleet, the downside clearly dominates. Beijing already has access to Russian resources at rock-bottom prices, and the very last thing it needs in seeking to foster a multipolar world is another North Korea.

Also unlikely: Russia collapses after defeat in Ukraine

The opposite extreme is that Russia will suffer a devastating defeat in Ukraine. If Ukraine is successful in reclaiming Crimea with military force, the humiliation will be such that it could very well bring the final push that causes the Russian Federation to collapse. There is a strong historical precedent in which Russian losses in war led to precisely this outcome.

It happened in the wake of the Livonian war (1558-83) when Muscovy collapsed. History repeated itself in the wake of its defeat by Germany in World War I, which ushered in the end of the Russian Empire. And it took place at the end of the Cold War when the Soviet Union disintegrated and the Russian Federation came close to falling apart as well.

While such a legacy may be preordained, it does emphasize that Russia has failed, over the centuries, to build strong civic institutions that can step in and keep the ship afloat when the government fails.

Given how doggedly the Putin regime has worked on cementing autocratic rule, with no room for alternatives, it is highly likely that if the linchpin is removed then the whole edifice will come unstuck.

President Putin is showing increasing concern about this outcome. In early June, he called on the governor of Magadan, Sergei Nosov, and other regional leaders to secure Russian territorial integrity by developing programs to stem the outflow of ethnic Russians and to block secessionist moves.

Ukraine has begun encouraging unrest among ethnic minorities across the Russian Federation. Dating back to the 1890s, the ethnic Ukrainian minority in the Russian Far East is of particular interest, as it might spearhead secession. In January this year, the secretary of the Russian Security Council, hardliner Nikolai Patrushev, warned that since Ukrainians in the region have retained their Ukrainian identity, they constitute a threat to Russian territorial integrity.

From a Chinese perspective, a breakup of the Russian Federation would have strongly negative consequences. It would undermine its geopolitical agenda, casting doubt on Russian rights to retain a seat on the United Nations Security Council. It would raise questions concerning long-term contracts on resource extraction. And it would saddle Beijing with a need to step in to provide governance and maintain order, simply to protect its own interests.

An independent Far Eastern Republic would be rich in resources. Aside from hydrocarbons and forestry, it holds very large deposits of diamonds, and it has a large fishing industry. The downside is that it would have weak administrative resources, ranging from foreign trade and payment systems to infrastructure and social services.

A declaration of independence would also provoke a military outcome like what happened when Ukraine broke free from Russia, in the aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet Union. While most of the strategic assets that would carry nuclear weapons, like long-range bombers and Borei-class submarines, would follow orders to retire to Western Russia, to a truncated state resembling medieval Muscovy, some might defect and proclaim loyalty to the new state.

This would leave Beijing with two possible outcomes – either the Russian Pacific Fleet is gone altogether, or it is reduced to a minuscule force in conflict with Muscovy. Although the odds for this scenario are long indeed, the consequences are so dramatic that it must be assumed to form part of the calculus when Beijing considers the need to prevent the Russian Federation from breaking up.

More likely: With China’s help, a weakened Russia survives

The likelier middle-of-the-road scenario envisions the formal survival of the Russian Federation as an internationally recognized entity. From a Chinese perspective, this would be highly welcome. Moscow would be able to continue supporting its geopolitical agenda, at the Security Council and elsewhere. It would guarantee that long-term contracts remain valid, and it would ensure that critical financial and transport infrastructure is kept running.

The downside is that it would have strong elements of the classic Potemkin facade. Behind the scenes, a weakened federal center would be faced with fierce battles for access to resources, where resource-rich regions are tempted into playing hardball with Moscow and resource-poor regions are cast adrift. It would be a highly unstable situation, prone to eruptions of violent conflict. It could drag on for years, and it would gradually veer toward one of the two extreme scenarios.

Unless something drastic happens that triggers a collapse of the federal center, the likeliest scenario is that the Russian Federation will remain formally intact but becomes progressively weaker. It is possible that this will eventually provoke a military takeover that transforms Russia into a scaled-up version of North Korea, but this is unlikely. The likely outcome is that progressive erosion causes increasing paralysis of the federal government, to the point where vital government functions are eroded to the point of collapse.

The implication for China is that to protect its vital interests in critical Russian regions like the Far East it will have to be prepared to step in, ideally to prevent a collapse of the Russian Federation, or, if that fails, to ensure a modicum of governance that includes basic social order, a functioning payment system and the orderly conduct of foreign trade.

This adds an important dimension to speculation about the willingness of the Middle Kingdom to support Russia in its war against Ukraine. Although Beijing would prefer to stand aside, as Russia drifts toward disintegration and state collapse, the specter of spillover into the conflict over Taiwan will inevitably force it to step up its support.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.