Russia’s Middle East resurgence: Here to stay?

In the Middle East, Moscow is seeking to reclaim its Soviet-era influence to advance the global ambitions of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

In a nutshell

- Russia’s military intervention in Syria enhanced perceptions of its power

- As a major oil producer, Russia seeks influence with Middle East competitors

- Arms sales in the region provide the Kremlin with revenue and influence

Despite the significant challenges the Russian Federation faces in its war against Ukraine, Moscow is still extraordinarily active diplomatically around the globe, including growing ties with North Korea and China.

Another region of renewed Russian strategic interest is the Middle East, where for nearly a decade it has been attempting to challenge the United States and others for influence, hoping to return Moscow to a position of power in the region not seen since the Soviet era.

Supporting this revival is Russia’s ambition to play an outsized role internationally, emblematic of President Vladimir Putin’s desire to return his country to its former “glory” as a global, rather than just a regional, power.

Mr. Putin infamously remarked that the Soviet Union’s demise was “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe” of the 20th century. He is taking his grievances about how the Cold War ended into the 21st century. His dictatorial rule is driven by fervent nationalism as well as by attempting to create a lasting legacy among the most widely known Russian or Soviet leaders.

With the war in Ukraine a burning issue for the Kremlin and Russian foreign policy, a key question is whether this Russian renaissance in Middle East relations will last.

Read more by Peter Brookes

Instability 2024: Hotspots and flash points to watch

Russia and North Korea: Similar bed, different dreams

Ukraine’s long path to victory and NATO

Russia’s Middle East interests

Russia sees itself as a great power with global interests. Its current involvement in the Middle East is no surprise, considering its geography and history in the region, especially its involvement from the Soviet era. Russia became immersed significantly in Middle East matters in 2015, when it stepped up to support the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad in Syria during its bloody civil war. Russia (and Iran) likely rescued the Assad regime from the dustbin of history.

While Russian interests have and will continue to vary from country to country in the Middle East, several themes are central to current Russian national interests in the region under Mr. Putin, including:

Great power competition: Russia is contesting for political, economic, informational and military influence in the Middle East not only with the U.S. but also with China, as part of the new global great power competition.

Influence in Middle Eastern disputes, such as Arab-Israeli troubles and the Syrian civil war, and transnational security issues, such as Iran’s nuclear (weapons) program, enhances Moscow’s real and perceived power internationally, for better or worse.

Energy frenemies: Russia is a major global energy producer and a competitor of many of the energy-rich countries of the Middle East such as oil powerhouse Saudi Arabia and natural gas giant Qatar.

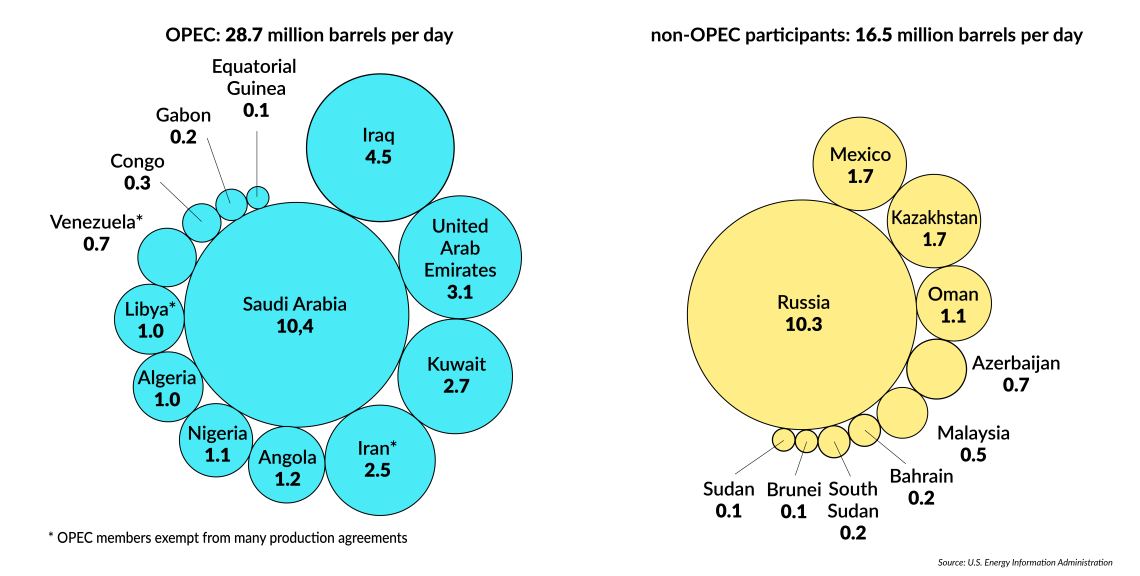

While not a member of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), the powerful oil cartel, Russia is a member of OPEC+, an affiliated group of 10 other major oil-producing countries.

Since OPEC is dominated by Middle Eastern countries that set oil production levels and, consequently, global prices, Moscow seeks cooperation and influence within it to benefit Russia’s government coffers.

Profitable partnerships: While Moscow avoids formal alliances in the Middle East, it does work to gather and develop strategic friendships that advance its interests, including mitigating its international isolation over the Ukraine war.

Today, in Syria, Russia makes use of an air base (Latakia) and a naval base (Tartus). These bases give Russia access not only to the Middle East, but an ability to project power into the Eastern Mediterranean, including sea lanes to, and from, the Black Sea – not to mention against NATO’s southern flank.

Moscow has also infamously developed ties with Tehran, especially on defense matters. Iran has been providing Moscow with impactful unmanned combat aerial vehicles (both armed and surveillance drones) for use in the Ukraine war.

Lastly, with Russia laboring under significant punitive Western international economic sanctions due to the war in Ukraine, willing Middle Eastern nations can give Moscow access to commercial and financial markets to secure critical materiel (such as microchips) and limit Russia’s economic exile.

Arms trade: Russia is the world’s number-two arms exporter behind the U.S. Those export rankings apply to defense transfers to the Middle East, too. Arms sales are an important element of the Kremlin’s international engagement. Egypt, Syria, Iraq and Iran are all major Russian defense clients.

Russian arms sales, especially high-end systems such as fighter aircraft and air defenses, provide Moscow with revenue as well as political access and leverage in those countries that purchase its systems.

While arms transfers are likely to see a drop because of battlefield losses in the Ukrainian campaign, production capacity and questions about the quality of Russian arms, the Middle East market will continue to be significant to Moscow.

Violent extremism: Russia is not immune from Islamist terrorism and separatism. It has suffered several significant attacks from terrorists and other internal groups. A few thousand Russians were reported to have traveled abroad to become foreign fighters among al-Qaeda, Islamic State and their affiliates. Accordingly, counterterrorism cooperation with Middle Eastern countries is a consequential internal security issue for Moscow.

The Middle East’s Russian interests

Big power plays: The Middle East has long been an unsettled region. The region is rife with rivalry and animus based on history, geography, ethnicity and sectarianism, among other issues, and has weathered its share of military conflict as a result.

As such, Middle Eastern countries often seek an extra-regional “balancer” such as the U.S. or Russia – and increasingly China – for support in protecting and advancing their national interests and undermining unwanted regional or external pressures.

Besides signaling that Middle Eastern countries have choices among competing great powers, these suitors can also be played off one another to maximize support and benefits, including economic aid and other assistance.

Energy competition: Russia produces nearly as much oil as Saudi Arabia. As such, the petrostates of the Middle East have a mutual interest with Russia in preserving and protecting beneficial global energy market conditions.

Beyond OPEC+, Middle Eastern natural gas-producing nations engage with Russia in the Gas Exporting Countries Forum (GECF). While not currently analogous to OPEC, GECF could become a natural gas cartel at some point.

International assistance: Russia is also valuable to Middle Eastern countries through its participation in international organizations such as the United Nations, where Moscow is a veto-wielding member of the UN Security Council. With this power, Russia can work to punish – or protect – member nations.

Beyond international organizations, influence may also apply to international agreements such as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (the Iran nuclear deal). Russia is one of the members of the mostly moribund agreement, which at some point may be revived in part or whole, or replaced completely, with Moscow’s involvement.

Defense collusion: Western arms, often preferred by nations for their quality (especially their capabilities and maintainability), are not always available for sale to Middle Eastern countries due to economic sanctions or restrictions based on human rights or political concerns.

Moscow is generally willing to overlook the objectionable domestic policies and practices of potential Middle East arms buyers, making Russian arms more available to these countries. (Russian arms are also relatively cheaper than the American alternatives.)

For instance, the Iranian military and its Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps will likely receive advanced Russian weapons despite concerns about Tehran’s bad behavior. Possible arms transfers to Iran include fighter aircraft and technical assistance to its ballistic/cruise missile and space/satellite programs.

Moscow will also likely provide feedback to Tehran on the record of its combat drones, and share intelligence and materiel gathered from recovered Western weapons used by Ukrainian forces.

Of course, the actual – and perceived – performance of Russian weapons on the battlefields of Ukraine will help determine how attractive Moscow’s arms are to Middle East customers in the coming years.

Facts & figures

Total oil production from OPEC+ (OPEC and non-OPEC members)

Scenarios

Russia is currently entrenched in the Middle East. But the looming question is whether policymakers, analysts and businesspeople should plan for a short-term or long-term Russian stay in the Middle East, and which factors may affect that decision?

Less likely: Short-term stay

Moscow could decide that it needs to focus on issues closer to home such as the war in Ukraine and domestic political, social and economic problems. Consequently, Russia may decide to reduce the time and resources devoted to Middle East engagement.

This scenario is possible should the Ukraine war slog on and the conflict become particularly troublesome at home due to the blood and treasure expended. While Russia is repressive and authoritarian, the Kremlin is cognizant of public opinion – and must take it into account.

For obvious reasons, the last thing President Putin wants is a so-called “color revolution” that overthrows the regime in a popular uprising, reprising the dissolution of the Soviet Union at the end of the Cold War.

Leaving the Middle East would not prevent a domestic rebellion over Ukraine policy, economic malaise or political frustration, but limiting engagement abroad to focus on issues at home could salve some of the numerous cuts and abrasions that the Kremlin has inflicted on the Russian people.

More likely: Long-term stay

Driven by a combination of nationalism and concern for his legacy, President Putin is committed to restoring Russia’s imperial grandeur. The Middle East might be the one key geographic area where Moscow can effectively play an outsized role.

Its existing influence with Syria and Iran, energy prowess, a powerful position in international organizations and arms sales give it significant standing. Playing a role in this pivotal region allows Russia to burnish its image not only at home, but abroad.

Moscow likely sees the Middle East as fertile ground for future Russian engagement as well, including competing with other great powers such as the U.S. and China for position and influence in the region.

For example, Russia is a major food producer, especially of wheat, and the Middle East is a major destination. Due to the region’s food insecurity, countries, especially Egypt, would welcome increased agricultural trade – especially while Ukrainian grain exports are stunted.

In addition, as a major exporter of nuclear reactors and fuel, Russia would also like to take advantage of the growing interest in (climate-friendly) atomic energy, including in the Middle East, where some countries are considering big-ticket projects.

In an environment of punitive international economic sanctions for Russia, access to friendly markets is critical.

Moscow’s influence in the Middle East may grow as well due to Russian migration to the region. According to some reports, there has been an expanding Russian diaspora in the Middle East, especially since the Ukraine war began.

For as long as Mr. Putin runs the Kremlin, the Middle East will likely be central to his strategy for Russia to be perceived – once again – as a great global power, and how he will be remembered for returning her to that exalted station.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.