Mali and Mauritania: Instability in the Sahel

Mali and Mauritania are both politically and economically fragile. In both countries, social divides and the state’s inability to control its own territory have led to the rise of radicalized armed groups. These challenges highlight the instability that threatens the Sahel region – a state of affairs that could lead to a wave of migration toward Europe.

In a nutshell

- In Mali, a 2015 peace accord is falling apart

- In Mauritania, the number of armed groups is growing

- These examples highlight the instability across the Sahel region

- The situation could send another wave of migration to Europe

Recent events in Mali and Mauritania highlight the fragility of the Sahel’s political and security outlook. If states in the Sahel region were to begin to fail, it would have extremely negative consequences for both Africa and Europe, leading to a drastic reconfiguration of security and political perspectives.

A fragile state

In 2012, several armed groups challenged the Malian government’s control over the state. They were motivated by various (and sometimes overlapping) political, religious and economic ambitions. The Tuareg ethnic group has historical and identity-related claims to territory, while the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO) wants to spread jihad across the region. Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) is determined to impose Sharia law across the region.

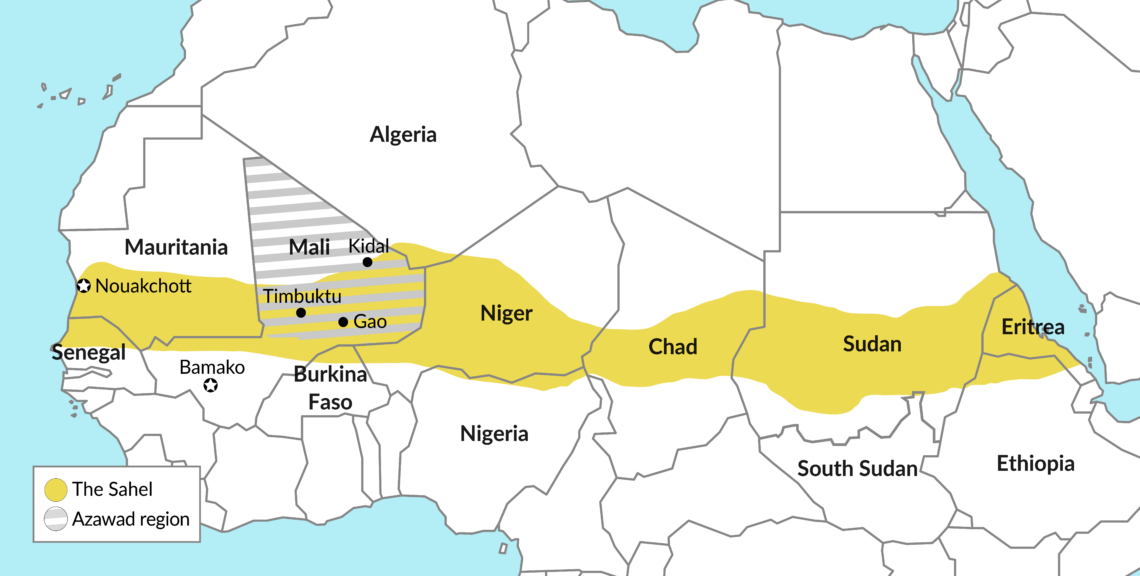

In January 2012, the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA) started an insurgency. Two months later, a coup by disaffected members of the military led to the fall of President Amadou Toumani Toure. Soon after, the MNLA unilaterally declared the independence of Azawad, a vast region in the country’s north. The power vacuum generated by Mr. Toure’s fall led to the emergence of Ansar Dine, a group allied with AQIM, which blended the MNLA’s independence aspirations with Islamic militancy. MUJAO, AQIM and Ansar Dine gained control of large swaths of territory, including the cities of Kidal, Gao and Timbuktu.

In 2013, the UN established MINUSMA to help secure Mali. The force now has 15,000 soldiers and police officers.

The speed at which these events took place and their potential consequences led to an unprecedented regional and international response. In 2013, the United Nations Security Council established the Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) to help secure the country. The force now has 15,000 soldiers and police officers, and its mandate has recently been extended for another year. In February 2014, Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania and Niger established the G5 Sahel, a regional platform for security cooperation.

In August 2014, the French launched Operation Barkhane, an anti-insurgent initiative throughout the G5. It is France’s largest overseas military operation, with 3,000 soldiers and an annual budget of some 600 million euros.

The United States and the European Union also have troops in Mali, through the Trans-Saharan Counterterrorism Initiative and the EU Training Mission. In 2017, the EU, France, Germany, the United Nations Development Programme, the World Bank and the African Development Bank created the Sahel Alliance, whose goal is to help stabilize the region through development programs.

Regional and international forces managed to recover the territories occupied by the MNLA and, for a time, limit the range in which the terrorist groups were able to operate. Seven years after the MNLA rebellion, however, the overall security situation is rapidly deteriorating.

Multiple threats

Ibrahim Boubacar Keita, president since 2013, was reelected in 2018 with 67 percent of the vote. International observers reported irregularities during the vote, but ultimately found that there was no fraud. Recently, the Constitutional Court has invoked force majeure (the unfavorable security situation) to extend the National Assembly’s mandate until May 2020. Two main factors are behind the country’s persistent instability.

First, the Malian government and two Arab-Tuareg rebel coalitions have failed to implement the 2015 Algiers agreement, which was supposed to end the conflict. The deal assumed that stabilization would result from a combination of integration (by co-opting key political actors and implementing disarmament and demobilization programs), decentralization (by devolving power to regional assemblies) and development. Distrust between the parties, excessive international intervention and unrealistic goals have prevented the agreement from being implemented.

Facts & figures

Instability in the Sahel

Northern Mali, with its power vacuum and porous borders, remains an attractive environment for terrorist and criminal groups. In 2017, elements of AQIM, Al-Mourabitoun (another jihadist organization) and Ansar Dine announced that they would merge into Jama’a Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin (the Group to Support Islam and Muslims). Over the past two years, the organization has attacked the Malian army, G5 Sahel forces, MINUSMA and elements of Operation Barkhane.

Having lost its “caliphate” in Iraq and Syria, the Islamic State has recently recognized the Islamic State in Greater Sahara (ISGS) as an affiliate. ISGS was created in 2015 and has been particularly successful in recruiting from Mali’s Fulani ethnic group.

The second factor is the upsurge of violence between seminomadic herders and sedentary communities in Mali’s central regions. The increasing scarcity of land and water, combined with the erosion of local authority, has fueled violence. So-called “self-defense” groups have cropped up, often mobilized along ethnic and occupational lines.

Development prospects are also weak: Mali ranks 182 out of 188 countries in the United Nations Human Development Index and demographic pressure is extremely high (the country has a fertility rate of six children per woman). For the most part, health and education services are inadequate or absent.

A militarized state

Mauritania, which shares a 2,237-kilometer border with Mali, is a state with no nation: it remains divided along ethnolinguistic and religious lines. With just over 4 million people, three-quarters of the country’s territory is desert or semi-desert. In a region marked by political and security turmoil, Mauritania’s apparent stability is the result of a highly militarized state and a deeply stratified society.

President Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz, a general who came to power in 2008, refrained from seeking a third term in the June 2019 elections. His successor, Mohamed Ould Ghazouani, also a high-ranking general and member of Mauritania’s political establishment, won the election with 52 percent of the vote, thus narrowly avoiding a runoff. While the opposition contested the results, the military remains the country’s ultimate decision-maker. In Mauritania, political change is treated cautiously both internally and internationally. This year’s elections marked the first transfer of power without a coup since the country gained independence in 1960.

This year’s elections marked the first transfer of power in Mauritania without a coup since independence in 1960.

The main opposition to Mauritania’s ruling party is the National Rally for Reform and Development (RNRD). The RNRD has an Islamist platform and is connected to the Muslim Brotherhood. The regime in Nouakchott alleges the opposition party receives support from Qatar. In 2018, President Abdel Aziz declared a political war against the RNRD, accusing it of extremism. He ordered the closure of Islamic universities and banned the Muslim Brotherhood. Not surprisingly, during the 2017 Gulf Cooperation Council crisis, Mauritania aligned with Egypt and Saudi Arabia against Qatar.

Besides these political and religious divides, Mauritania is also a rigidly stratified country (it was the last country in the world to abolish slavery, in 1981). Under President Abdel Aziz, slavery was designated a crime against humanity and special courts were established to address the matter. Still, between 1 and 20 percent of the population (international organizations’ findings vary widely) is affected by slavery. Moreover, there remains a deep divide between an elite largely composed of Arab-Berbers and the Haratine (former slaves).

Political and social cleavages are aggravated by an economy which encourages rent seeking and neopatrimonialism. The economy is extremely dependent on the mining sector, with iron ore and gold accounting for 46 and 11 percent of the country’s exports, respectively. Unemployment is estimated at 40 percent, and most people depend on agriculture for survival. However, arable land accounts for only 0.5 percent of the country’s territory.

A new Afghanistan?

UN aid agencies have recently announced that the Sahel crisis has reached unprecedented levels, marked by food shortages (an estimated 29.2 million people experience food insecurity, 9.4 million of which severely), forced displacement and escalating violence.

Faced with the potential of Mauritania becoming a new Afghanistan – a territory where crime and radicalism flourish thanks to porous borders, state failure, political fragmentation and chronic poverty – the EU has invested significant sums in stabilizing the Sahel region. Besides military and security cooperation, between 2014 and 2020, Brussels will have spent an estimated 8 billion euros in development aid. In December 2018, the EU announced additional funding of 125 million euros, including a 70 million-euro emergency stabilization program in Sahel border areas.

Violence will likely increase, as the number of armed non-state actors continues to grow.

Despite these considerable efforts, violence will likely rise, as the number of armed non-state actors continues to grow. These include local, regional and international terrorist groups, self-defense militias and criminal networks. The groups establish alliances with each other that are looser or stronger depending on the circumstances. Their operational capacity is likely to grow faster than states’ ability to control their own territory.

The number of terrorist attacks has risen, especially in countries going through transitions (such as Burkina Faso, which is still struggling to transition to democracy following the fall of former President Blaise Compaore), or where the state is fragile.

Scenarios

Considering the current political security and political context in Mali and Mauritania in particular, and in the Sahel region in general, two broad scenarios should be considered.

Long war on terror

Under this first, more likely scenario, the Sahel will remain the stage of a war on terror for decades. Though the number of terrorist groups is expected to increase, and their reach widen, key regional and international actors (including the U.S., the EU and France) will deploy enough hard power to confine them to a limited geographical area. The Sahel will become the new focal point for counterterrorism cooperation.

Security, rather than democracy, will remain the top priority, meaning militarized and “strongman” regimes will prevail. Despite successes on the military front, the road to development will be long and tortuous. Factors like demographic pressure and resource scarcity (especially water and land) will continue to compromise growth, as will high unemployment and underdeveloped economies.

Chronic insecurity in specific areas (northern Nigeria, northern and central Mali or the Lake Chad region) will make it harder to break the vicious cycle of violence, state weakness, underinvestment and extreme poverty. Poor development prospects mean that migration will remain a critical issue for Europe. Trafficking networks will remain strong.

The Hobbesian scenario

Under this somewhat less likely scenario, in the coming years, jihadist groups and transnational criminal networks would gain control of large portions of Sahel territory. This scenario would be triggered by chronic political instability or state failure. State failure could either include state collapse or the consistent inability of certain states to exercise power in certain regions, as both their legitimacy and monopoly on the use of force erode. Mali, Nigeria and Niger are particularly vulnerable. Political destabilization in key security actors in the region (like Algeria or Chad) could also trigger this outcome.

Past months have seen an increase in jihadist violence in Burkina Faso, Mali and Nigeria. There are strong indicators that, following defeats in Iraq and Syria, terrorist groups with territorial ambitions are shifting their attention to the Sahel.

Given the growing number of armed groups, the disintegration of state power in the Sahel would initially lead to a Hobbesian “war of each against all.” Power here has historically been diffuse and informal trade particularly profitable. Under this scenario, jihadist groups, transnational criminal networks and nomadic and seminomadic tribes would fight (and establish strategic allegiances when suitable) to control territory and key trade routes. Trafficking in humans, weapons and drugs would likely rise.

The increase in criminal activity, violence and instability would negatively impact countries in West Africa and the Maghreb, as well as those states which are already in fragile positions, such as South Sudan and the Central African Republic. This scenario would also have significant security and political consequences for European countries, especially if instability befalls one of the Maghreb buffer states.

With today’s global uncertainty, weak growth and political polarization, EU countries are particularly vulnerable to external shocks. The emergence of a major and potentially uncontrollable security threat across the Mediterranean would test the limits of the European project.