Singapore’s foreign policy under new leadership

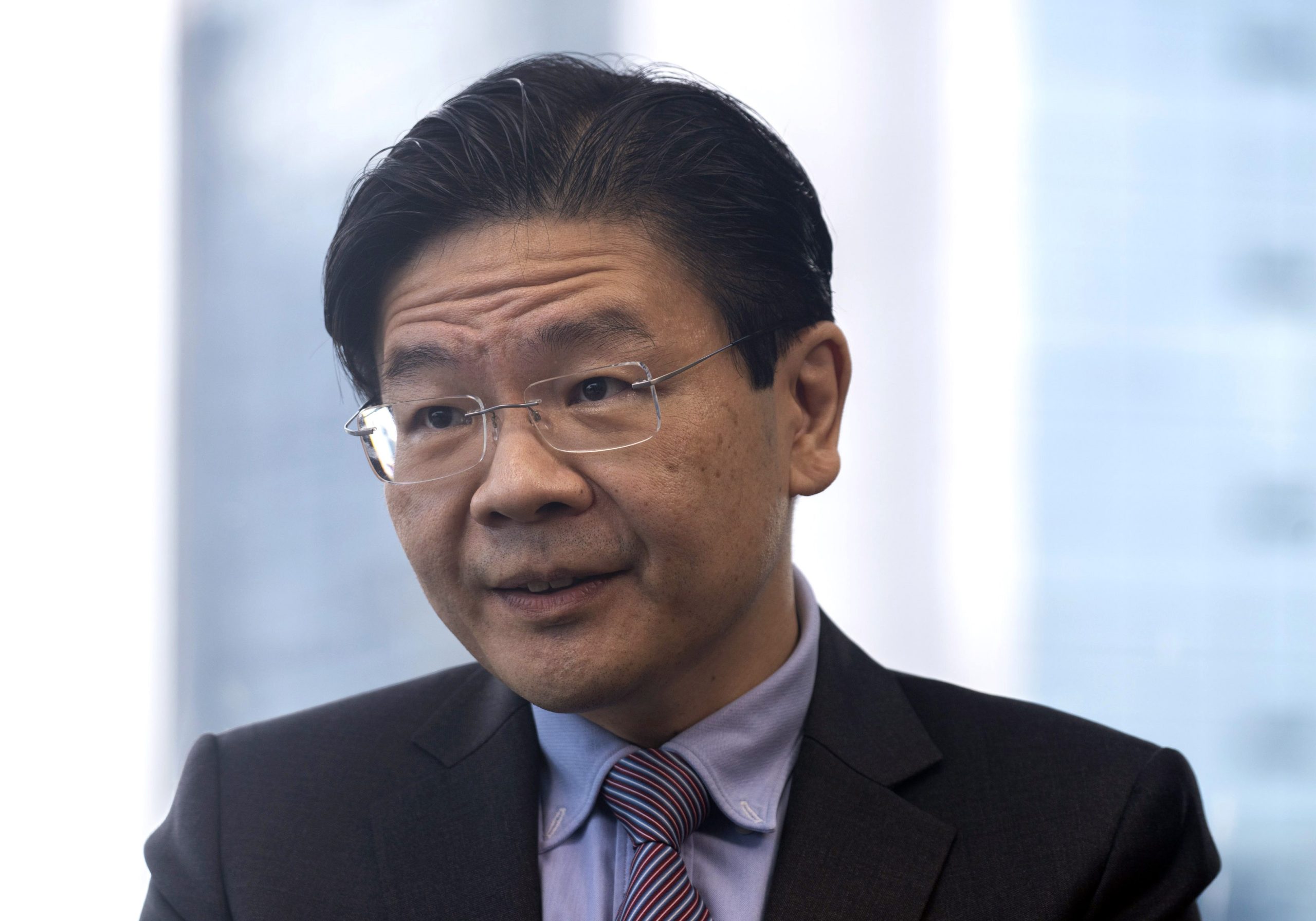

Lawrence Wong’s foreign policy approach as Singapore’s fourth premier will be rooted in the successes of his predecessors, but he faces extraordinary pressures.

In a nutshell

- Singapore has a consistent foreign policy approach based on diplomacy, as well as military strength and norms

- The country’s strategic position is challenged by U.S.-China competition, regional instability and domestic political shifts

- Future foreign policy will likely emphasize stability and continuity, and leverage existing partnerships

Lawrence Wong’s ascendancy as Singapore’s fourth prime minister has cast a spotlight on one of the region’s most diplomatically active countries. Few expect disruptive changes in foreign policy. Singapore’s international engagement is built on a decades-old foundation of political stability and economic growth. But the broader question remains how the country’s foreign policy engagement is likely to evolve amid regional and global challenges.

Mr. Wong enters his first term as prime minister – from May 15, 2024 – with no apparent plans to fundamentally alter Singapore’s foreign policy, which has been consistent under the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) that has governed the country since its separation from Malaysia in 1965. The country’s approach relies on actively cultivating diplomatic relationships, investing in military capabilities and supporting norms undergirding a rules-based order such as open trade.

These factors have been key to Singapore’s survival – and success – as a small but active state that has punched far above its weight. While occasional developments such as the so-called “small state debate” have highlighted some differences in views in the country, these are part of an enduring elite consensus. Mr. Wong has served decades in this system, including previous roles covering defense, education and energy. He is also part of a wider, years-long transition process to fourth-generation (4G) leadership.

Facts & figures

Singapore’s 4G leadership

Singapore’s use of the term “4G” refers to the “fourth-generation” group of leaders currently taking over governance from the previous, or third-generation, leaders.

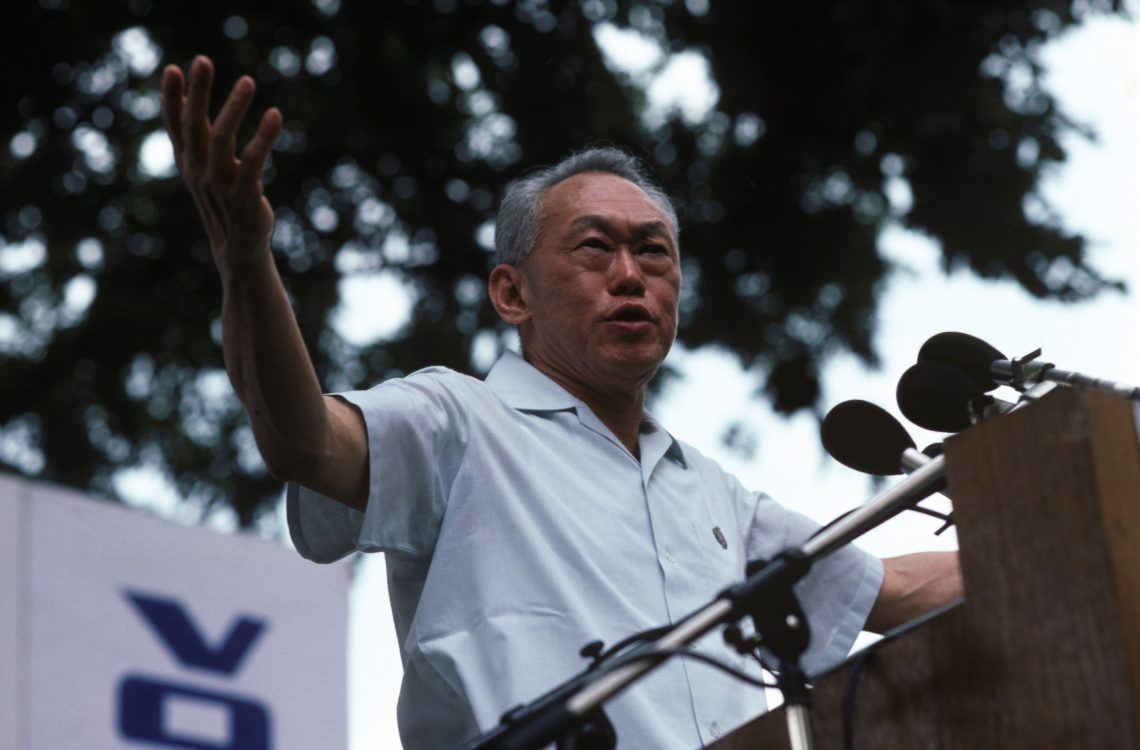

The concept of numbered generations of leadership has long been a part of Singapore’s political narrative, especially within the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP). The first generation was led by Lee Kuan Yew, who was the country’s founding prime minister and is widely credited with transforming Singapore from a developing colony into a prosperous global city-state. The second generation was led by Goh Chok Tong, followed by the third generation under Lee Hsien Loong, the son of Lee Kuan Yew.

The 4G leaders are expected to continue this legacy of prosperity, but they also face their own set of challenges, including managing economic restructuring, maintaining social cohesion and addressing strategic geopolitical shifts. This group is composed of younger politicians who, having been groomed through various ministerial roles, embody a generational shift in leadership as they are expected to bring new perspectives and policies to address Singapore’s future needs.

At the same time, his tenure will take place as Singapore faces a more challenging environment. Abroad, Mr. Wong himself has warned that trends such as the backlash against trade, strained institutions and U.S.-China competition suggest an external environment that is “less benign and hospitable for small states like Singapore.”

Singapore’s leaders also worry that these circumstances could affect the trajectories of not only major powers, but also its neighbors, Indonesia and Malaysia, which could in turn affect bilateral ties. At home, while the PAP retains political dominance, the opposition has made periodic inroads and the ruling party has seen more scrutiny at times.

Singapore’s leaders have also expressed concern about rising foreign interference, with divisive issues such as the Israel-Gaza war undermining the country’s social compact. The only ethnic Chinese-majority state in Southeast Asia, Singapore is also home to sizable Malay and Indian minorities, and lies between two Muslim-majority countries (Indonesia and Malaysia), which has at times resulted in tense episodes.

Scenarios

Most likely: Singapore remains an important player on the international scene

Here, while Singapore would still confront manifold challenges, its leaders would be able to ensure that it preserves its position as a key global hub, continuing to play an active role internationally building on longstanding foreign policy fundamentals.

Globally, this would include continuing to craft sectoral agreements in the digital and green economy as well as taking a leadership role in shaping standards in areas like artificial intelligence.

Regionally, Singapore would also remain actively engaged as Southeast Asia struggles to manage flashpoints such as the Myanmar civil war, the South China Sea disputes and intensifying U.S.-China competition. It would also be a key node in bilateral cooperation or regional integration even amid geopolitical headwinds. This could include realizing ambitious cross-border projects with Malaysia and improving regional energy connectivity, even if this falls short of an explicit ASEAN-wide power grid. This trend would continue in the coming years, including when Singapore next holds the annually rotating chairmanship of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 2027.

Less likely: Contestation hits Singapore’s foreign engagement

Singapore, faced with a fragmenting world, could see fierce divisions at home. This could strain the country’s internal harmony, increase tensions among the ruling elite, and affect aspects of the PAP’s performance amid opposition inroads.

These dynamics could in turn affect some of Singapore’s foreign policy decisions. Growing pressure and coercion from China (as seen previously) may affect Singapore’s delicate balance between valuing Beijing’s economic significance and maintaining its role as a key U.S. security partner.

Closer to home, growing nationalism or rising identity politics in neighboring Indonesia and Malaysia could spill over and upset the country’s social compact. Contestation could also erode Singapore’s competitiveness as a regional and global hub, which rests on its reputation for political stability. These concerns are not merely hypothetical. As Lee Kuan Yew noted in a key foreign policy speech in 2009, Singapore’s success in staying competitive rests on its ability to “remain a cohesive, multi-racial, multi-religious nation based on meritocracy.”

Least likely: A more constrained Singapore internationally

Here, Singapore would see a decline in its status as one of the region’s most diplomatically active and militarily proficient countries. This would in turn begin to impose constraints on the ability of the ruling regime to be as active internationally as it would like.

In one version of this scenario, slowing economic growth could erode the ruling regime’s popularity, raising questions about defense spending and strengthening resistance to foreign workers despite the country’s aging population. If Singapore’s leaders find that they have to respond to these pressures by cutting defense budgets and severely restricting immigration, this risks eroding Singapore’s deterrence and its foundation as a regional talent hub. This could in turn complicate Singapore’s relationships with its Southeast Asian neighbors and make it more vulnerable to threats from foreign powers.

Given Singapore’s global relevance, these dynamics will be closely scrutinized by international observers. In the major 2009 speech, Lee Kuan Yew noted with his characteristic bluntness that Singapore will survive and prosper as long as future generations of Singaporeans “do not forget the fundamentals of our vulnerabilities, and not delude themselves that we can behave as if our neighbors are Europeans or North Americans, and remain alert, cohesive and realistic.” That is likely to remain a generational foreign policy test for Mr. Wong and Singapore’s 4G leaders in the coming years.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.