Supranational bodies do not thrive in Africa

Supranational organizations play a role in some regions of Africa. However, they inherently oppose the notion of state supremacy, meaning they face resistance in a continent largely made up of postcolonial states founded on the ideals of independence and sovereignty.

In a nutshell

- Africa is not a very integrated continent by most criteria

- The African Union and regional organization play a limited role

- The continent’s main challenges remain national in nature

In Africa, accelerated globalization and attempts at continental and regional integration have been accompanied by the creation of some supranational and interstate organizations. Such organizations represent a challenge to the idea of state sovereignty. They face additional difficulties on a continent of postcolonial states, where identity divides and armed conflicts persist.

Without a doubt, cooperation and integration have contributed to economic advances in some regions of Africa, and, in several instances, help maintain peace. However, to the extent that they are oriented toward integration rather than interstate cooperation, supranational organizations do not help advance African states’ maturation process. In many cases, they even erode governmental responsibility, claiming more authority and decision-making power, broadening their own agendas and trying to impose their rules.

Multiple organizations

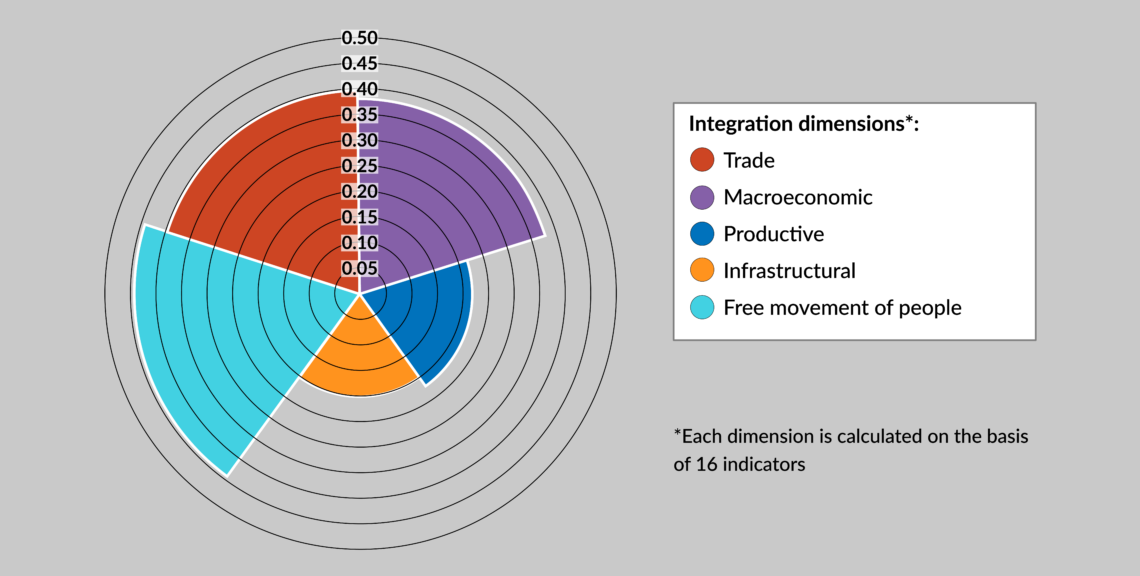

According to the Africa Regional Integration Index (ARII), which measures levels of integration on a scale of 0 to 1, based on five “dimensions” and 16 indicators, South Africa is the most integrated country on the continent with a score of 0.625. The region with the highest levels of integration is West Africa, followed by East Africa. Trade and other macroeconomic factors, as well as the free movement of people, are the biggest drivers of integration. On the other hand, infrastructure and production remain relatively unintegrated among countries.

Paul Kagame led an ambitious reform program for the African Union, but its weaknesses remain.

The leading supranational organization on the continent is the African Union (AU), which succeeded the Organization of African Unity. Headquartered in Addis Ababa, the self-styled capital of “the African Renaissance,” the AU aims at “promoting unity and solidarity of African states,” spurring economic development and promoting international cooperation. Its 2002 constitution embodies the idea that sovereignty is not an absolute prerogative and must be balanced with the responsibility to protect. Also, it has allowed the creation of more powerful political institutions and security mechanisms, such as the Pan-African parliament and the African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA). However, the role of the AU in solving African crises has fallen short of expectations, mainly due to inefficiency and poor coordination, financial dependency and lack of political will.

The AU is now at a crossroads, as it gained momentum in 2018, under the chairmanship of Rwanda’s charismatic President Paul Kagame. He was responsible for launching a highly ambitious reform program for the organization. However, in practice, the Assembly of Heads of State and Government and the Peace and Security Council remain highly politicized and unable to implement decisions on the ground. As for regional organizations, the most relevant are the Economic Community of Western African States (ECOWAS), created in 1975, and the Southern African Development Community (SADC), established in the present form in 1992.

Facts & figures

Aside from leading a reasonably successful process of economic integration (through the promotion of the free movement of people, capital, services and goods, and the harmonization of development policies), ECOWAS plays a vital role in political and security matters in West Africa. The organization, through its zero-tolerance policy regarding irregular changes of power and robust peace and security mechanisms, was pivotal in restoring peace in Liberia, ending the conflict between Laurent Gbagbo and Alassane Ouattara in Ivory Coast, guaranteeing the return to civilian rule after the 2014 ouster of Blaise Compaore in Burkina Faso and securing a peaceful leadership transition in Gambia in 2017.

Even though it has been the most effective regional organization on the continent, ECOWAS remains hostage to rivalries between anglophone and francophone countries. It finds it increasingly difficult to maintain its zero-tolerance policy and remains dominated by Nigeria. Its headquarters is in Abuja, and Nigeria contributes more than 40 percent of the payments made by member states.

A strengthened African Union provides countries on the continent with more leverage at the global level.

Another key actor in Africa’s geopolitics is the SADC. Its origins go back to the 1960s and the so-called Frontline States’ struggle against minority rule in Southern Africa. After the end of apartheid in 1994, South Africa became the natural leader of the organization. Given the specific legacy of settler colonialism, especially in South Africa and in Zimbabwe, the overarching value of the SADC was the fight against imperialism. However, that lofty claim increasingly served to legitimize the perpetuation of authoritarian regimes, as was the case with Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe until 2017.

Steps forward and obstacles

Regional integration in Africa, stemming from the creation of Regional Economic Communities (RECs), has helped economic performance and development, even if the benefits are not spread evenly across the continent. The RECs increased intraregional trade flows, stimulated economies of scale, and aided the free movement of people, knowledge and technology.

On top of that, supranational and interstate organizations bolstered order and peace by instituting security mechanisms and platforms for dialogue in a continent pummeled by conflict. In a diverse continent where countries are experiencing different stages of development and undergoing an ambitious, accelerating process of continental integration, the “building blocks” logic – according to which regional blocks are the cornerstones of integration – brings several advantages. At the same time, a strengthened African Union provides countries on the continent with more leverage at the global level, as shown by the current debate on debt repaying terms.

However, the roots of Africa’s main challenges – state fragility, authoritarianism, identity rifts and high unemployment rates – remain national in nature. They are often neglected by the supranational organizations, which – pressured by global organizations – increasingly tend to focus on “global causes” such as climate change.

Also, the proliferation of regional organizations with increasingly comprehensive mandates has been used by African politicians, including authoritarian leaders, as channels to access international funding, increase their domestic leverage and project their image in the international arena.

Multilateralism does not always improve African countries’ prospects.

Such dynamics, often amid overlapping jurisdictions and competencies, contribute to inefficiency by multiplying costs and reinforcing complex decision-making processes. There is a gap between official discourse calling for democratization and good governance and the practices of organizations like the EAC, the SADC or the AU, which on numerous occasions have favored incumbent (and authoritarian) leaders.

Finally, and from a global perspective, these organizations are particularly vulnerable, as donor dependency makes them a potential Trojan horse to the ambitions of great powers – particularly China. Aside from its network of bilateral arrangements, Beijing has been trying to extend its influence in Africa through United Nations agencies and African supranational organizations.

Scenarios

Events in Africa suggest that multilateralism and supranationalism do not always improve the countries’ political and security prospects. In the Sahel, for example, security remains a tremendous problem despite multiple interventions led by regional and international actors. Moreover, despite the dominant discourse, there are signs – going well beyond the effects of the Covid pandemic – that the world may have entered a phase in which globalization is slowing down, if not outright reversing. This process is driven by realpolitik, not internationalism.

In this context, two scenarios emerge.

Under the more likely one, economic integration in Africa will be accompanied by attempts at political integration through multilateralism and supranationalism. Given the high levels of financial dependency that characterize these organizations, and their overall inability to address security crises, Africa will remain overexposed to the influence of global agencies and China. The attempts at political integration will probably fail in the medium to longer term, given the absence of a common set of values and identity, the essentially national nature of security and political obstacles and their spillover effects.

Moreover, several African countries are expected to experience either political change or armed conflicts. Instability is a tremendous obstacle to the projects of political integration and supranationalism. Under this scenario, despite the official rhetoric, most African regional and subregional powers will likely focus on reaping the benefits of economic integration while selectively engaging in security cooperation through mechanisms such as the G5 Sahel or the Accra Initiative. They will not cede more sovereignty to supranational organizations.

Under the second, less likely scenario, Africa would follow the ASEAN model. Regional and continental integration would focus on trade, investment and specialization through the progressive elimination of tariffs and barriers to the free movement of people, goods and services, and the development of economies of scale, as envisaged in the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA).

In this context, African countries could benefit from higher levels of investment because competitor regions – such as Latin America – present higher risks. This approach, however, would encounter two critical obstacles. The first is the absence of regional leaders, since the two continental giants cannot lead. Nigeria seems determined to maintain its protectionist impulses on the economic front and its hegemonic ambitions on the political front. And South Africa is going through a deep political and economic crisis.

Although other regional players are emerging – as evidenced, for example, by the increasingly visible role of Ghana in West Africa or Rwanda in East Africa – there is no substitute for these giants in the short to medium term. Secondly, to be successful, economic integration requires processes of productive integration and adequate infrastructures. Whereas recent efforts to include the private sector in regional and continental dynamics may help, the infrastructure gap in Africa remains significant, and mobility levels are low, especially in central Africa.