Tigray conflict escalates

Addis Ababa maintains its forces have quelled the conflict in the Tigray region, but tensions endure. Should a full-blown, multiethnic civil war erupt in Ethiopia, the consequences for both the country and the region could be profound.

In a nutshell

- Ethiopia’s stability and unique federal system are under severe strain

- The country's leading ethnic groups feel threatened by reforms

- Nobel Peace Prize winner and Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed is hardening his policies

While Prime Minister of Ethiopia Abiy Ahmed claims to have secured control in the Tigray region, tensions will have profound and long-standing consequences at both the domestic and regional levels. A prolonged conflict involving multiple actors could destabilize the Horn of Africa. The failure of Ethiopia’s ethno-federal system could impact the political outlook in fragile states such as Somalia.

Ethno-federalism

After the defeat of the dictatorial regime of Mengistu Haile Mariam (1977-1991) at the hands of the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), Ethiopia gravitated toward ethnic federalism. This model crystallized in its constitution of 1995.

In the decades that followed, the country became an example of authoritarian development under a dominant-party system in which regional states maintained a measure of autonomy. Within the EPRDF – an armed movement that morphed into a coalition of parties formed along ethnic and regional lines – the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) was the most potent force.

The grievances and claims became broader than their initial trigger, and the protests increased in number and intensity.

That power translated into the disproportionate role of Tigrayans (who account for about 7 percent of Ethiopia’s 110 million population) in the military and intelligence structures and an economy characterized by centralized patronage and rent-seeking. Nevertheless, under Prime Minister Meles Zenawi (1995-2012), Ethiopia – although far from being a democratic regime – became a symbol of the African renaissance. A key regional power, it scored remarkable gains on the economic and developmental fronts.

However, the prime minister’s sudden death in August 2012 marked the beginning of an end of this good run.

Tigray conflict

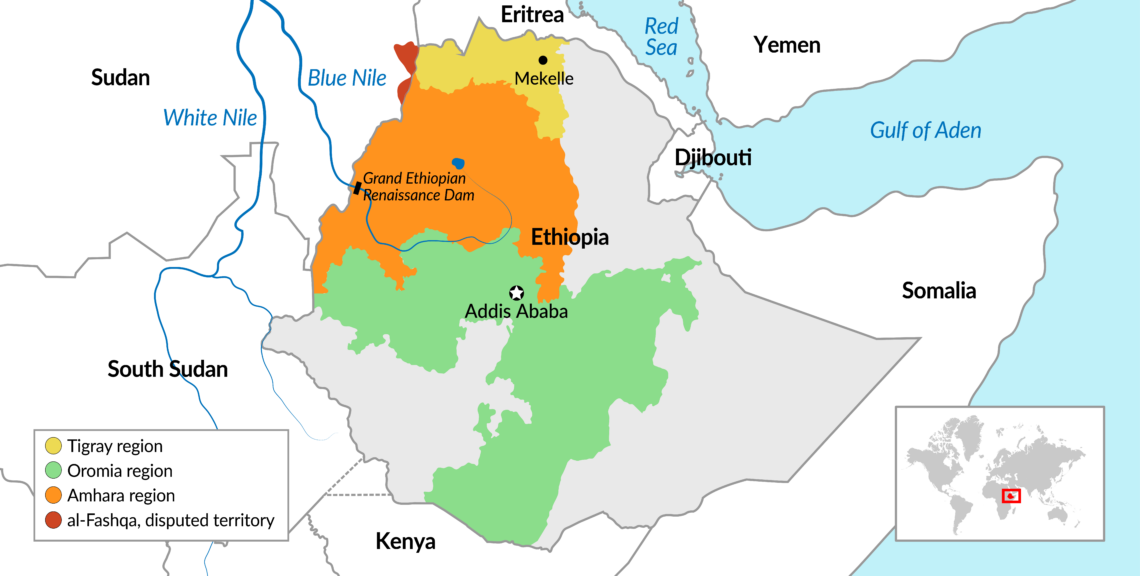

In 2014, the Oromo people began protesting a scheme to expand the boundaries of Ethiopia’s capital city into Oromia territory under the so-called Addis Ababa Master Plan. When the federal government eventually suspended the plan in 2016, it was too late. As sometimes happens, the grievances and claims became broader than their initial trigger, and the protests increased in number and intensity, spreading from the Oromo into the Amhara region. Oromo and Amhara are the two largest ethnic groups in Ethiopia, accounting for 34 and 27 percent of the population, respectively.

The protests led to a recalibration of power within the ruling EPRDF as Abiy Ahmed, the son of a Muslim Oromo father and a Christian Amhara mother, was appointed prime minister in 2018. Once in power, he implemented far-reaching reforms, including what was then seen by many in the domestic and international spheres as a process of political opening. The prime minister ordered the release of political prisoners, lifted bans on media outlets and reached out to opponents and long-standing enemies like Isaias Afwerki, president of neighboring Eritrea.

These moves, however, were seen by some political actors – especially in the TPLF party – as motivated by anti-federalist and centralizing impulses and biased against members of the Tigrayan ethnic group. Tigrayans were the leading targets of Mr. Abiy’s anti-corruption campaign.

Quick escalation

By 2019, the conflict reached a point of no return. Ethnic violence was escalating. When the prime minister merged the EPRDF coalition into a unified, pan-Ethiopian structure, the TPLF, which had been the dominant force within the ruling system for decades, refused the merger, arguing that it was unconstitutional.

The escalation of tensions was both quick and predictable. When, in 2020, the federal government unilaterally canceled elections due to the Covid-19 pandemic, Tigray defied the decision. Its balloting was held in September, granting the TPLF a landslide victory. The federal government announced that it would no longer recognize that state government and suspended the transfer of federal funds.

Armed conflict erupted on November 4, 2020, when the TPLF ordered attacks on the Northern Command of the Ethiopian National Defense Forces. Some weeks later, the federal government announced that its “law and order” operation had succeeded, and it had taken control of the regional capital, Mekelle. However, by then, the conflict was closer to a civil war, transcending regional states’ borders, than to a policing operation.

Facts & figures

Amhara militias and Eritrean troops intervened in the fight against the TPLF and other Tigrayan rebel groups. In the campaign, characterized by massive violence against civilians, sexual violence and the destruction of crops and livestock, parts of Tigray territory have allegedly been annexed. As a result, more than 45,000 refugees fled into Sudan, and the estimated number of internally displaced exceeds 500,000. According to the UN, more than 4.5 million people – or 80 percent of the region’s population – are now dependent on food assistance.

The regional dimension

The Horn of Africa, the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden have become vital locations for Africa’s security and competition between global powers. And in the region, Ethiopia – an ally of the United States – has become an economic and political powerhouse and an agent of stabilization, containing Eritrea, contributing to counterterrorism efforts in Somalia and mediating the Sudanese transitional process.

Tensions over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam are critically straining relations between Addis Ababa, Khartoum, and Cairo.

This position of regional strength started to change in 2018 after Ethiopian and Eritrean leaders signed a peace deal in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Then, over protestations from the U.S., the UN Security Council lifted its arms embargo on Eritrea, a personalized, totalitarian and heavily militarized regime. And now, that regime is accused of committing atrocities against civilians in Tigray.

At the same time, hostilities between Ethiopia and Sudan are increasing due to border disputes in al-Fashqa, Amhara region, while tensions over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam are also on the rise, putting relations between Addis Ababa, Khartoum, and Cairo in a critical situation. Egypt’s President Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi has already warned that he will not tolerate a scenario under which operations in the dam threaten water supply and livelihoods in Egypt. As the first round of talks failed, Moscow is now mediating the dispute.

In the region long tormented by violence, famine and displacement, the new refugee crisis triggered by the Tigray conflict is hugely disruptive. Tigrayan refugees are fleeing into neighboring Sudan, where the humanitarian and political situation also happens to be critical. Moreover, recent tribal clashes in West Darfur threaten a domino effect on the already fragile South Sudan.

Scenarios

Clash of two governance system

With legislative and regional elections scheduled for June, Ethiopia’s political and security situation is expected to remain tense throughout 2021. As he tries to consolidate his leadership, Prime Minister Abiy faces stiff challenges. Multiple tensions are forcing him to negotiate with different actors, and there are signs that he may have lost control over the Tigray situation.

The Amhara elite has supported President Abiy’s attempt to bring the mutinous state back under control. The support of Amhara constituencies will be critical for the Prosperity Party in the upcoming elections. However, following its forces’ offensive in Tigray, the Amhara civil administration has claimed control over the Western fertile lowlands. Moreover, clashes between the Sudanese Armed Forces and the Ethiopian National Defense Forces (ENDF) have undermined a long-standing compromise over the lands claimed by Sudan and tilled by Amhara farmers in the al-Fashqa Triangle. At the same time, the U.S. and the European Union have increased diplomatic pressure over Prime Minister Abiy, demanding the withdrawal of Eritrean troops and redeployment of Amhara forces from Tigray.

It is against this background that a more political dispute will take place next in Ethiopia. In the contest between the federalist system in effect until now and the centralized and pan-Ethiopian model pushed by Prime Minister Abiy, two base scenarios emerge.

A limited stabilization

Under this, slightly more likely script, the prime minister would win the June elections, and the Tigray region would remain the stage of a protracted conflict between multiple actors. Pressures exerted by the U.S. and the EU – including the suspension of foreign aid – would force Mr. Abiy to negotiate with Eritrea and the Amhara leadership their presence in the Tigray. However, the interference of these forces in the region and the atrocities committed against civilians will leave scars and resentment among Tigrayans, who will resist the federal state.

Therefore, a successful strategy of negotiation or co-optation is unlikely. A protracted, if localized, conflict remains the most likely outcome, one which will carry a high humanitarian cost. However, this scenario will not materialize if the Amhara leadership withdrew their political support for the Prosperity Party.

The outcome of the political and armed conflicts in Tigray will also shape the relational dynamics between the federal government and other regions.

Full-blown civil war

Under this less likely scenario, the conflict in Tigray would degenerate into a civil war and, eventually, a regional conflagration.

While the main actors involved, including Ethiopia’s prime minister, are keenly aware of the exorbitant human, political and economic costs associated with such a scenario, the fragile positions of Sudan and Eritrea may contribute to an escalation of tensions.

The Sudanese military could see an armed conflict with an external enemy as an opportunity to increase its internal leverage. For his part, Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki, who rules with an iron fist a country with a population of 3.5 million people, with a system of universal conscription and a 200,000-strong army, may see in a revival of war the only opportunity to remain in power.

A scenario of prolonged internal and (or) regional conflicts accompanied by the abrupt disintegration of Ethiopia’s ethno-federalist system would have far-reaching consequences. Besides its potential political effects in neighboring countries – including in Somalia, where President Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed makes a determined push for subordinating its federal states to the central authority – it would also lead to a dramatic deterioration of the security outlook of the Horn of Africa.