Japan after Tokyo 2020: Back to power politics

The Tokyo 2020 Olympic games, although a resounding success, came at a tremendous cost. With Yoshihide Suga having resigned less than a year after taking office, the next prime minister of Japan will have to face Beijing’s increasingly aggressive stance in East Asia.

In a nutshell

- The Tokyo 2020 Olympics were highly politicized

- Yoshihide Suga has resigned ahead of the leadership race

- Japan is in the midst of a crucial geopolitical realignment

The Tokyo 2020 Olympics were among the most successful games ever held. The performance of both organizers and athletes surpassed even the highest expectations. But what impact did this gigantic show have on Japan?

The official price tag stands at $15.4 billion, making them the most expensive games on record. The postponement from 2020 to 2021 added an additional $2.8 billion to the original price tag.

While politicians praise the games as a platform for peace, they are also a forum for intense national competition. The daily obsession with the medal scoreboard reflected political rivalries. During the Cold War, the United States competed against the Soviet Union. This time, the world watched to see if China would overtake the Americans.

Beijing’s shadow

The Tokyo Summer Olympics will be closely followed by the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing. While it is too early to speculate how the Covid-19 pandemic will affect the event, there will undoubtedly be intense scrutiny to assess whether China outperformed Japan as a host.

The Tokyo Olympics caused a lot of political commotion. A large majority of the Japanese electorate was in favor of canceling them altogether. The games also exacerbated the intense geopolitical rivalry between China and Japan.

During the pandemic, the Japanese turned against the games and Prime Minister Suga’s popularity plummeted.

In autumn 2013, Japan placed its bid to host the 2020 summer games to show the world it had overcome the Fukushima disaster. Nobody could imagine that a virus would derail the whole project and delay the games. During the pandemic, the Japanese turned against the games, calling for their cancellation. Consequently, Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga’s popularity plummeted.

Beijing kept a close eye on the Tokyo Olympics. Chinese nationalists see their country as a new superpower equal to the U.S., and the undisputed hegemon of Asia. They also see Tokyo as a power in decline. Once Japan had the second-largest economy in the world and the largest foreign exchange reserves in the world, only to be overtaken by China.

Under the leadership of Xi Jinping, the People’s Republic has become more assertive and more conscious of its soft power. Beijing wants to outdo Japan, and it will use all its influence to ensure there will be no boycotts or protests condemning human rights violations in Hong Kong or Xinjiang.

Strategic crossroads

In postwar Japan, socioeconomic development took place by leaps and bounds, a remarkable feat for a nation that puts so much emphasis on tradition and continuity. In 1964, Tokyo hosted the Olympic Games, showing the world that it had recuperated from the devastation of World War II. The launch of the bullet train served to emphasize that Japan was now among the most technologically advanced nations.

Tokyo 2020 did not provide the excitement and the optimism Prime Minister Shinzo Abe had hoped for when he launched the bid. Instead, Japan gained new insights into the power politics shaping a new era in East Asia.

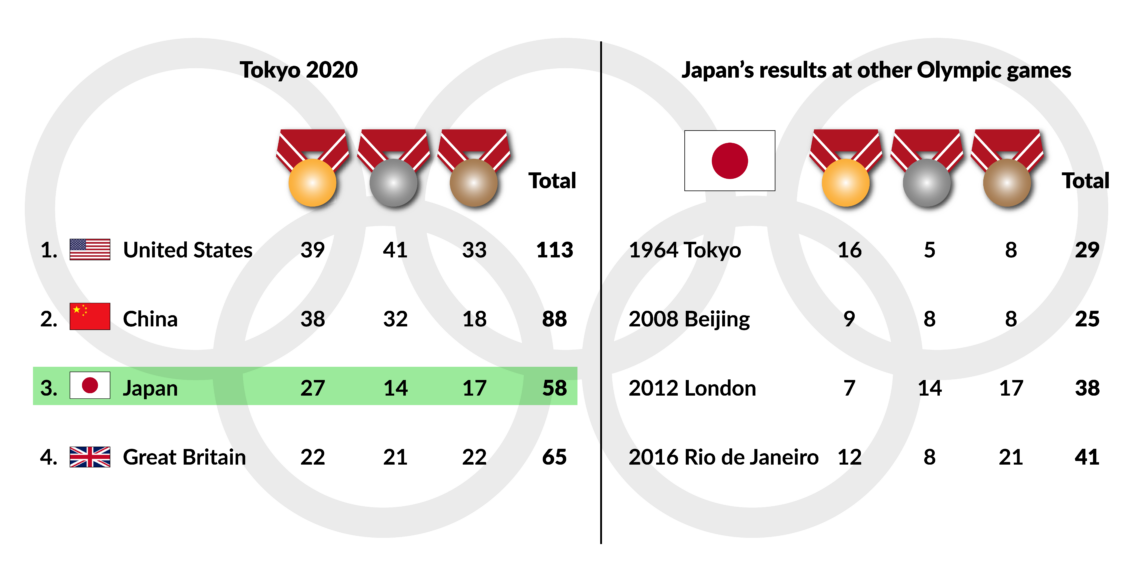

Looking at the medal tally, China stands out. Japan did not do badly, and Japanese athletes performed well overall. But the demeanor of the Chinese could not be mistaken: they were representing Asia’s new superpower.

Facts & figures

Sporting prowess does not define a nation’s geopolitical sway, but it can offer insight into a country’s general mood and self-confidence. Japan made tremendous efforts to show its best face to the world and achieved remarkable success. However, the massive health precautions required by the pandemic, including the decision to restrict attendance, cast a cloud over the event.

Now that the games are over, geopolitical realities take center stage once again. While international media focused on the Olympics, Tokyo published its annual defense white paper. The release went largely unnoticed, although the document contained a significant departure from past practices in mentioning, for the first time, Taiwan as a significant security concern.

Over the past five years, Japan has been reassessing its geostrategic orientation, partly of its own volition, partly because it has been forced to do so by external circumstances. The Taiwan question is a major pivot. For the past half-century, Tokyo did everything it could to avoid raising the issue for fear of irritating Beijing. Only very recently has the government begun to articulate its security interests in Taiwan. A number of Japanese politicians have made bold statements about how Japan should react in case of a military attack against the island, which the Chinese leadership describes as a “rebellious province.”

For Japan, a lot is at stake in how the Taiwan issue eventually will be resolved.

Taiwan is a thorny issue in Sino-Japanese relations. For 50 years, from 1895 to 1945, the island was a Japanese colony. For Beijing, reunification is an internal issue, which, if necessary, will be solved by force. Any Japanese support for the defense of Taiwan is therefore an interference in the internal affairs of the People’s Republic.

For Japan, a lot is at stake in how the Taiwan issue eventually will be resolved. While it is up to Washington to deter China from attacking, a military takeover would create a dangerous precedent. The Japanese archipelago of Okinawa, home to the largest American bases in Japan and one of the most important pillars for the Western presence and defense in Asia, could be targeted next.

Suga’s exit

With his ratings in free fall, on September 3 Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga threw in the towel. He had been in office less than a year. It had become evident that his prospects for reelection as leader of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) on September 29 were very dim. Already several potential candidates had openly defied him.

The LDP has an elaborate system of party factions. Mr. Suga had been able to claim the top spot after serving under Prime Minister Shinzo Abe as chief cabinet secretary, a position that had allowed him to muster backing from different groups. Most recently, with his ratings falling, his support within the LDP began to dwindle. The names of several other candidates were put forward and there was even a rumor that Mr. Abe himself might return.

It could benefit Japan and the Western world to avoid yet another string of short-term leaders.

Whoever emerges as the new leader of the LDP – and therefore as Japan’s new prime minister – will implement their own security strategy. Its impact will reverberate across Asia, especially now with rising uncertainty after the U.S.’s departure from Afghanistan.

Shinzo Abe’s eight-year tenure, the longest in postwar Japanese history, was both unusual and beneficial to the country’s foreign and security policy. Before him, there had been a period of revolving-door prime ministers lasting only a year or two.

In the longer term, the question now is whether the LDP will decide on a candidate who has farsighted ambitions, as well as the necessary power and stature to carry them out. In the present international climate, with important shifts in geopolitics taking place, it could benefit Japan and the Western world to avoid yet another string of short-term leaders.