Turkey’s balancing act on security

As the war in Ukraine drags on, Ankara is weighing its strategic interests in the region and the wishes of NATO partners.

In a nutshell

- Ankara hopes to reduce its reliance on the U.S. and NATO

- Conflicts along several Turkish borders are posing political risks

- Next year’s election season may shape Turkey’s security policy

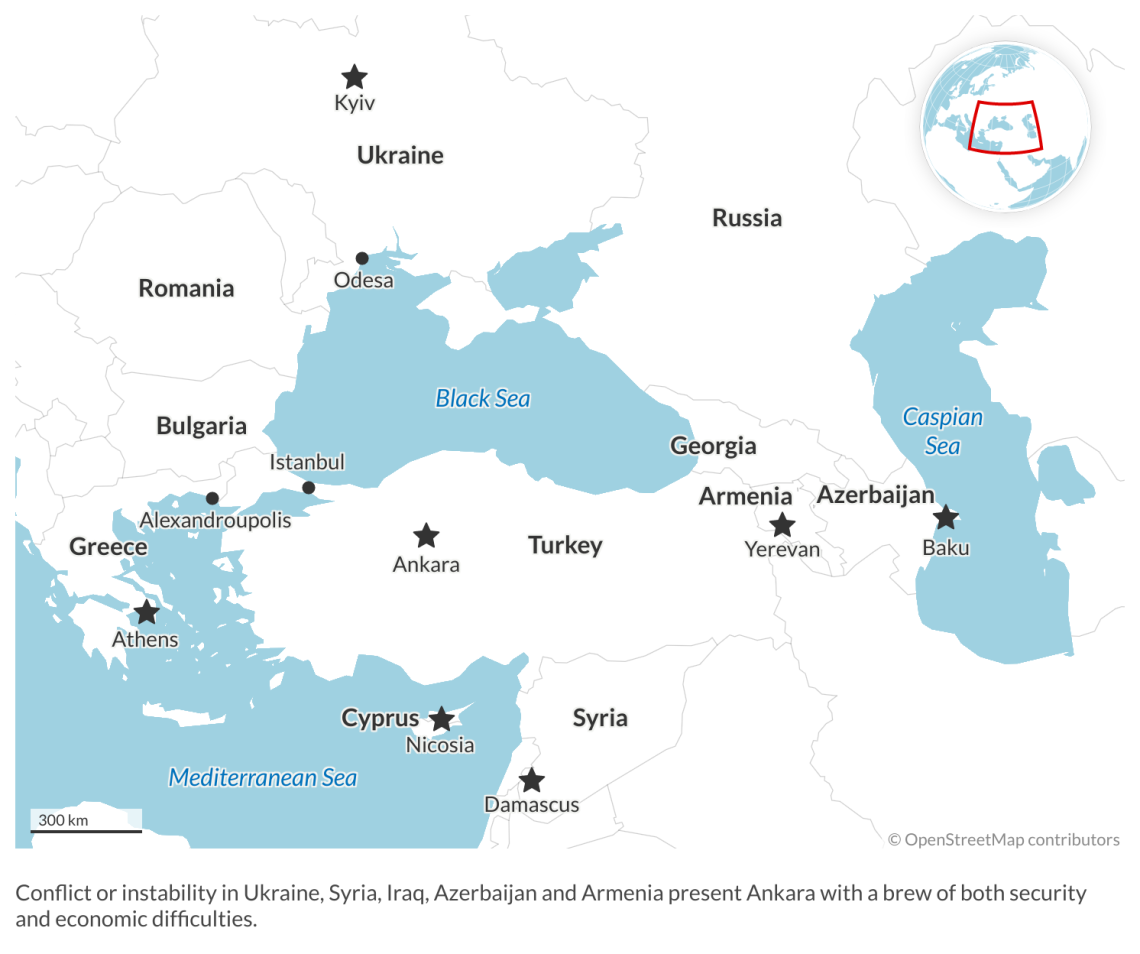

From Ankara’s viewpoint, the war in Ukraine has added yet another element to the mix of dangerous tensions along several of Turkey’s frontiers. In recent years and months, disputes in the eastern Mediterranean over gas drilling and sovereignty have intensified, raising the stakes from the Aegean islands to the waters around Cyprus.

At the same time, the fighting in Syria with its complicated international entanglements has hardly subsided. The same goes for parts of northern Iraq, where the United States remains a factor and where Turkey is going after supposed Kurdish militants. A mounting weariness among Turks over the millions of Syrian “guests” in the country, as well as poor harvests in regions to its south, have exacerbated migratory pressures both into and out of Turkey.

Meanwhile, with national elections next year set to coincide with the Republic of Turkey’s centennial, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan will have to weigh domestic political factors amid these precarious security concerns.

From Ottoman Empire to NATO bulwark

To understand Turkey’s likely security policies, it is worthwhile to cast a brief look back at its 20th century. In the aftermath of World War I, Austria-Hungary was totally dismembered, while Germany and its Central Powers allies were pressed to sign a number of harsh peace treaties in castles surrounding Paris (Versailles, Saint-Germain, Neuilly, Trianon, Sevres). The conditions imposed on the Ottoman Empire at Sevres were particularly devastating, practically ending viable statehood for the nation.

That led to a rebellion, led by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, against the dictates of the victors and the acquiescing sultan. The Turks’ military success led to the abolition of both the Treaty of Sevres and the sultanate, as well as a revised peace accord in Lausanne that roughly gave Turkey its present territorial shape.

The Republic of Turkey, founded in 1923, would later manage to skillfully weather the storms of World War II, staying neutral and avoiding getting drawn into the fight. However, Ankara joined with the West when the United Nations Security Council, with Russia’s seat empty in protest, voted to act militarily in the Korean conflict. Turkey lost many soldiers but was rewarded with NATO membership at the end of hostilities in 1952 alongside Greece.

NATO membership remains, in principle, the bedrock of Turkey’s military security. But looking after its own interests – without relying only on the U. S. and NATO partners – has become increasingly important for Ankara.

Oversized partner

Today, Turkey fields NATO’s biggest army in Europe, tapping into a reservoir of 85 million people, a population smaller than only Russia’s in Europe.

The country has increasingly found itself out of step with NATO and the U.S. That sentiment came to a head with the U.S.-led war against Iraq in 2003. Turkey’s populace has grown six times larger in the last century, but it perceives the surrounding security challenges as acutely as ever. These fears may seem unfounded or anachronistic to some in the West, but they are broadly shared in Turkey, from the top of government to the general public.

Ankara perceives its most important NATO partner as both a security supplier and a source of concern.

Political scientists have dubbed it the “Sevres Syndrome”: the old worry of having the state torn apart and virtually destroyed. Of course, it can sometimes be convenient to exaggerate these fears for tactical or domestic political purposes.

However, the hard reality is that the wars raging to its north, south and east – in Ukraine, Syria, Azerbaijan and Armenia – pose real headaches for Turkey. They weigh on the country in several respects, including economically, by bringing millions of refugees to care for. Ankara also now faces the challenge of navigating between Ukraine, a friend and prospective NATO peer, and Russia – the complicated yet indispensable antagonist, partner and energy provider.

U.S. ties

Now add the eternal worries about the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), the Kurdish militant group gnawing at Turkey’s southern borders, and top them with the Americans’ ambivalent presence in the Middle East. Ankara perceives its most important NATO partner as both a security supplier and a source of concern.

Just seven years ago, NATO support was highly welcome in securing Turkey’s southern border for as long as the Islamic State (also known as ISIS or Daesh) was infiltrating the country and occupying northern Syria. While the Islamic State was subsequently defeated, American support today for PKK-affiliated groups in Syria puts further strain on Turkey’s already fraught relationship with Washington.

Facts & figures

Meanwhile, Fethullah Gulen, the alleged mastermind behind the 2016 coup attempt against the regime of Turkish President Erdogan, operates freely from the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. Washington has refused to deliver the most advanced F-35 fighter jets to Turkey while offering them to Greece. A Patriot missile-defense deal with the U.S. has never materialized. At the same time, Washington later sanctioned Ankara for turning to the Russian S-400 alternative, citing risks to the security of NATO technology and personnel.

Greece and Cyprus

Adding further to Turkey’s laundry list of irritants is the unresolved Cyprus issue, which comes bound with the age-old conundrum of Greece. Relations with “the Greeks” have been a roller coaster for hundreds of years, with swapped territories, forced expulsions and population exchanges. But it has also seen an undeniable closeness, with much in common and episodes of genuine solidarity, such as in the face of natural disasters.

These days are again a period of saber-rattling, and upcoming elections in both Greece and Turkey are not relaxing tensions. Mr. Erdogan and his Justice and Development Party (AKP) urgently need a turnaround in popularity before next year’s ballot, which coincides with the much anticipated 100th birthday of the republic. Making the country again rally behind its leader – now in charge for nearly two decades – is the main challenge, and plans are now likely being weighed to somehow make it happen. For the time being, disunity among the opposition and the absence of a convincing opposition candidate play in Mr. Erdogan’s favor, but these by themselves are likely not enough to secure another term.

The EU’s granting of candidate status to Ukraine and Moldova deepened Turkish disillusionment about the body.

History helps understand the situation with Greece and when measuring the disappointment (especially in Turkey) triggered by 2004’s failed effort to solve the Cyprus issue. This author vividly remembers discussions among diplomats and pundits in Ankara, around 2015-2016, on the decline in Turkey-European Union relations from bad to worse.

The general belief was that the 2004 Cyprus referendum indeed marked a watershed. Ankara had high hopes for the implementation of the UN-proposed federal solution for Cyprus, drawn up under UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan (1938-2018). That was to be followed by the EU accepting a reunited Cyprus as a member, followed harmoniously by welcoming Turkey. The Greek Cypriot population rejected the so-called Annan Plan, yet a divided Cyprus was admitted as a full-fledged EU member state. The resulting shock in Ankara appears to have been profound and lasting.

The recent granting of EU candidate status to Ukraine and Moldova inevitably deepened Turkish disillusionment about the body. Before, EU leaders claimed to have learned from the Cyprus outcome and thus would not dream of letting in another candidate burdened by a bilateral conflict, such as Serbia or later Kosovo, without first sorting it out. And yet now, the EU has given an (albeit vague) promise of candidate status to Ukraine, a country engaged in a conflict of unpredictable scale and duration – although admittedly, not one of its own making.

Arms race

Turkey’s current disputes with Greece over the Eastern Mediterranean waters and expected natural gas deposits on the seabed, as well as the frantic efforts by both NATO partners to arm themselves, are products of a downward trajectory in the long-term Greece-Turkey saga. Ordinarily, one is tempted to say that such tensions tend to be diffused, ushering in calmer or even sunny periods. In the coming months, the attitudes of American, British and European partners toward their tug-of-war may prove to be decisive as economic rivalries and standing in the regional arms race come into focus.

As far as drones are concerned, Turkey has managed to develop its own and sell them worldwide, to significant success. It is safe to say that Ankara will not spare any effort to achieve a high degree of self-reliance in aeronautics as well.

In a famous 1964 letter, U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson warned Turkish leader Ismet Inonu not to use American weapons in the context of Cyprus. Similarly, the U.S. and several EU states are denying Turkey arms deliveries today, citing several factors. As in the past, such limits incentivize Turkey to intensify research and development on armaments. In 2016, I heard some Turkish industrialists relate a meeting with the minister of defense. He cited the case of Austria as an argument for why Turkey should accelerate its own arms production; at that time, the parliament in Vienna had adopted a (somewhat symbolic) declaration prohibiting Austrian arms sales to Turkey.

Scenarios

Ankara has little choice but to continue its balancing act on foreign and military policy. As in earlier eras, it wishes to associate and cooperate tightly with Europe (plus the U.S.) but struggles to find close and reliable partners there.

At the same time, with some other neutral or neutral-leaning nations, Turkey cultivates its other identities and alliances. It aims to be one of, if not the main, point of reference for the global Islamic community, as well as for Africa and the so-called “Turkic world” of Central Asia. It is already quite close to countries like Qatar, Libya and Somalia, entertaining a military presence in each, and is flirting with the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation.

In a volatile international context, with black swans seemingly ready to arise at any moment, the coming 2023 elections should nonetheless indicate what foreign and security policy direction the world can expect from Turkey. Four scenarios present themselves:

Muddling through

In the most probable scenario, in which the war in Ukraine drags on, Turkey may manage to continue muddling through. It would regularly (though only to a point) find itself at loggerheads with several NATO allies, particularly the U.S., Greece and France. Such a situation would mean relative, albeit fragile, stability. Turkey could play the migration card and take a harder line on the admission of Sweden and Finland to NATO. The threat could dissuade both the Europeans and the U.S. from attempting to punish Turkey, for a time.

Turkey’s strategic role as a bulwark against migratory pressures and as NATO’s firm southeastern cornerstone largely persists but may slowly be losing its unique importance. The U.S. has sought to build up the northeastern Greek city of Alexandroupolis as a military and liquified natural gas hub, possibly rivaling next-door Turkey.

The use of nuclear energy in Turkey has so far been entrusted to Russia, whose companies (together with Turkish partners) are expected to ready the country’s first nuclear power plant for the 2023 centennial year, thus further narrowing the country’s choices of energy provider. In the near term – before reactors being developed with Western partners are ready – Russia will remain the main player in the nuclear area.

In short, this scenario would bring more of the same, including unrestricted trade with Russia.

Escalation

The war in Ukraine and the underlying U.S.-Russia confrontation could escalate through 2022 and 2023, triggering NATO solidarity – in principle, forcing Turkey to play its part. This scenario could expose the country to major security risks and economic hardships, given its significant energy dependency on Russia and reliance on Russian trade and tourism. In a pre-election context, broad anti-American sentiment might play a more relevant role than usual, influencing government policy.

To secure Turkey’s allegiance, Western partners might thus wish to embrace Turkey, becoming more receptive to its requests and offering cooperation in fields from armaments to free trade, travel and visas. In theory, the West could try to bet on the Turkish political opposition, though such attempts could easily backfire given how unpopular both the opposition and the U.S. have been there.

Mediation

In a benign though a rather improbable scenario, Turkey may manage to help mediate a negotiated cease-fire between Ukraine and Russia. Ideally, from Ankara’s standpoint, this would lead to an “Istanbul Conference” (or a Congress of Vienna 2.0) aimed at returning peace and prosperity to Europe. While not currently on the horizon, this is Turkey’s optimal path and has already been pursued with some success, as with the July 2022 Istanbul settlements over grain and fertilizer exports from Ukraine and Russia via the Bosporus.

Course change

The least probable scenario could arise from a breakup of Western unity, owing to an intensification of the fighting in and around Ukraine, a full economic war between the West and Russia, and/or the consequences of energy, price and sociopolitical crises in the EU. This could prompt Turkey to reassess its posture.

A major change in Turkey’s security position could also be provoked by radical developments in the Middle East – such as destabilization following military escalation between Iran and Israel or a new series of domestic upheavals and their global ramifications. Turkey has already wisely taken up this thread with outreach to Israel, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia and even, via “technical communications,” Syria.