Turkey’s strategy for Africa

Since the 1990s, Turkey has been ramping up its activity in Africa, forging a comprehensive strategy that includes active diplomacy, social outreach and economic partnership. It also offers a “third way” for countries that don’t want to be a pawn in the U.S.-China power play.

In a nutshell

- Turkey is increasing its influence in Africa

- The initiative is mainly driven by domestic politics

- It offers countries an alternative in the U.S.-China rivalry

Since the 1990s, Turkey has been implementing a comprehensive, long-term strategy for engaging with Africa. Its approach is oriented more toward achieving domestic goals than foreign policy ambitions. Anchored in nationalism and increasingly authoritarian rule, Turkey also presents itself as an alternative to the Western model of liberal democracy and secularism.

Turkey unveiled its first “Action Plan for Africa” in 1998, when it was becoming clear that there might ultimately be no room for Turkey in the European project. The Africa policy gained strength in 2005 with the start of the “Opening to Africa” strategy. That same year, Turkey secured the observer status at the African Union. As Ankara became more ambitious, a new narrative emerged around the revival of the Ottoman Empire and Pan-Islamism. Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who after serving as prime minister for 11 years became president in 2014, presented the country as a growing regional power and an “Afro-Eurasian state.”

Domestic imperatives

To understand Turkey’s strategy in Africa, it helps to consider how the country’s internal dynamics influence its foreign policy.

Starting in the late 1990s, a transnational collection of Islamic associations, media outlets and schools known as the Gulen movement played a leading role in Turkey’s ventures into the African continent. The government, led by the Justice and Development Party (AKP), used the movement to project soft power across Africa, namely through cooperation in education and social initiatives. By 2013, there were over 100 Gulen-sponsored schools operating across the continent.

The coup attempt in 2016 upended the relationship between the AKP and its Gulenist allies.

The coup attempt in 2016 upended the relationship between the AKP and its Gulenist allies. President Erdogan blamed the failed coup on what he called a parallel state – a small faction in the army led remotely by his rival, Fethullah Gulen, the movement’s namesake. The Turkish government designated the group a terrorist organization, calling it the Fethullahist Terrorist Organization (FETO).

Ankara pressured African countries to crack down on the movement. Governments across the continent responded differently, but most granted Ankara’s requests. Many Gulen-backed schools were replaced by ones run by the Maarif Foundation, created by Turkey’s government in June 2016. Recently, Mr. Gulen’s nephew was arrested in Kenya.

Economic and security cooperation

Ankara also knows that the continent has become a vital stage for competition between global and regional powers, and believes it is crucial to secure an advantageous position in the scramble for opportunities on the economic and security fronts.

Turkey’s economic footprint in Africa has grown rapidly. Its foreign direct investment (FDI) in the continent recently passed the $6 billion mark, with more than 1,150 projects underway. Trade increased fivefold between 2003 and 2019, from $5.5 billion to more than $26 billion. Air travel has played a crucial role in this growing partnership: there are now 52 African cities served by Turkish Airlines, and that number is expected to increase.

Facts & figures

Like Russia, Turkey sees Africa as a key customer for its defense industry. It has signed a series of arms deals with African countries, including Kenya, Uganda and Tunisia. Again, this international strategy bolsters domestic goals, as Ankara wants to strengthen its defense manufacturers and become self-sufficient in the sector by 2023, the Republic of Turkey’s centenary. Commercial deals have been accompanied by increasing diplomatic activity: Ankara has established at least 37 military offices across the continent and signed agreements for military cooperation with several countries, including Chad, Niger and Somalia.

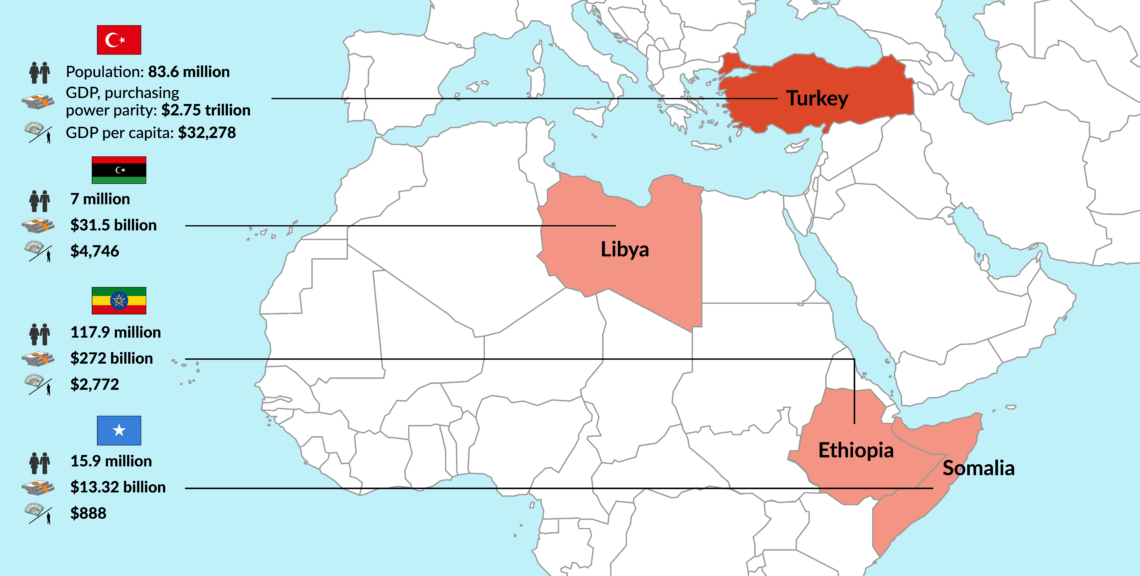

From a geopolitical perspective, three countries are particularly relevant in Ankara’s African ambitions.

The first is Somalia, which offers a gateway to the Indian Ocean and provides strategic access to the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden. Along with Djibouti, Somalia is a key point for competition – and tension – between Arab states. In 2011, as the country was going through a dramatic crisis, President Erdogan visited Mogadishu and offered humanitarian aid. Since then, Ankara has provided Somalia with more than $1 billion in aid and investments, including the construction of roads, hospitals and schools. In 2017, Ankara opened a military base in Mogadishu, Camp TURKSOM, which also includes a military training center. One year later, allegedly at the request of the Somali authorities, the United Arab Emirates ended its military training program in the country. Recently, Ankara paid off $2.4 million of Somalia’s debt to the International Monetary Fund.

Libya also plays a critical role in Turkey’s strategy for Africa, due to Ankara’s ambitions over disputed waters and resources in the East Mediterranean, as well as its rivalries with other powers. Following an agreement between Turkey and the United Nations-backed Tripoli government, Turkish forces have been providing training and support to the Libyan Armed Forces. Turkey’s rivals – the UAE, Egypt, and France – had all supported, either implicitly or explicitly, a competing Libyan government based in Tobruk that was backed by the forces of Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar. Ankara’s prominent role in Libya has been accompanied by intensifying military and economic cooperation with Tunisia and Algeria – the latter now being Turkey’s second largest trading partner on the continent.

Turkey’s strategy for Africa is comprehensive in both its priorities and geographic reach.

Ethiopia is another strategic ally for Ankara. Turkey is the country’s second main investor after China, with Ethiopia accounting for more than a third (around $2.4 billion) of overall Turkish FDI in Africa. Besides its strategic location in the Horn of Africa, Ethiopia is also a gateway to East Africa where Turkey has been increasing its economic activity, namely through major investments in Rwanda in the energy, health and construction sectors.

Comprehensive strategy

These examples show that Turkey’s strategy for Africa is comprehensive in both its priorities and geographic reach. It includes not only military cooperation, trade, investment and airline diplomacy, but also cultural tools. Turkish soap operas, for example, have conquered millions of viewers in large markets like Nigeria and Ethiopia. Moreover – as with China but unlike the European Union or the United States – it is a highly coordinated strategy. The expansion of trade links goes hand in hand with the establishment of diplomatic missions (the number of Turkish embassies on the continent increased from 12 in 2003 to 43 by 2021) and military cooperation.

Turkey also benefits from some competitive advantages that it will likely retain in the medium and long term. Unlike its European competitors, Turkey has no colonial past haunting its relations with Africa. And in contrast with China, Turkey cannot – at least for now – be accused of predatory policies, neocolonialism, creating debt traps, or providing low-quality goods and services to African countries.

Turkish influence will grow in the Sahel and West Africa.

Moreover, Turkey has several attributes that resonate with African countries averse to becoming pawns in the global U.S.-China competition: its status as a regional power trying to consolidate its position in the global arena, its nationalist and pro-sovereignty narrative, and President Erdogan’s mantra that “the world is bigger than five” (referring to the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council).

Scenarios

The future of Turkey-Africa relations will hinge on three factors: the evolution of Turkey’s economic and political circumstances; the political and security prospects in places that are critical for Ankara’s Africa strategy (including North Africa, Ethiopia and Sudan), and the competition between global and regional powers on the continent.

With President Erdogan and the AKP set to remain in power, it is likely that Turkey will see through its long-term strategy for Africa. African countries’ increasing willingness to test out new alliances with powers will bolster its goals and have political consequences in the region. A recent example occurred in Somalia, where troops trained at Camp TURKSOM were deployed to suppress protests against election delays.

Turkish influence will grow in the Sahel and West Africa now that France has decided to reduce its military presence there, while the U.S. may also pull back. Ankara’s efforts to engage with Senegal, Gambia, Guinea Bissau, Nigeria, Niger and Chad show how crucial it considers the region in containing the Gulen movement.

In the Horn of Africa, domestic events in Sudan and in Ethiopia will determine future scenarios. In Sudan, President Erdogan had signed important agreements with former President Omar al-Bashir. These agreements have lost strength, as the transitional coalition seems to favor engagement with the West. In Ethiopia, where the outlook for stability remains uncertain, the UAE and Saudi Arabia are challenging Ankara’s influence. In this context, the dispute over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam has become a crucial issue. Ankara continues to take Addis Ababa’s side against Egypt, which opposes the dam’s construction.

From a global perspective, the most important question will be whether Turkey’s strategy helps contain China’s influence on the continent. Though Ankara’s growing influence in Africa does not fit into U.S. President Joe Biden’s strategy of an “alliance of democracies,” the third way offered by Turkey and its need to retain its alliances with the EU and the U.S. will likely benefit Western interests.