Why U.S.-China ‘soybean diplomacy’ is overhyped

Despite resurgent trade in the vital commodity, soybean sales between Washington and Beijing have more to do with markets than geopolitics.

In a nutshell

- The soybean trade is less geopolitically relevant than some claim

- Sales have usually only been affected by periods of trade tension

- U.S. and Chinese officials continue to regularly engage one another

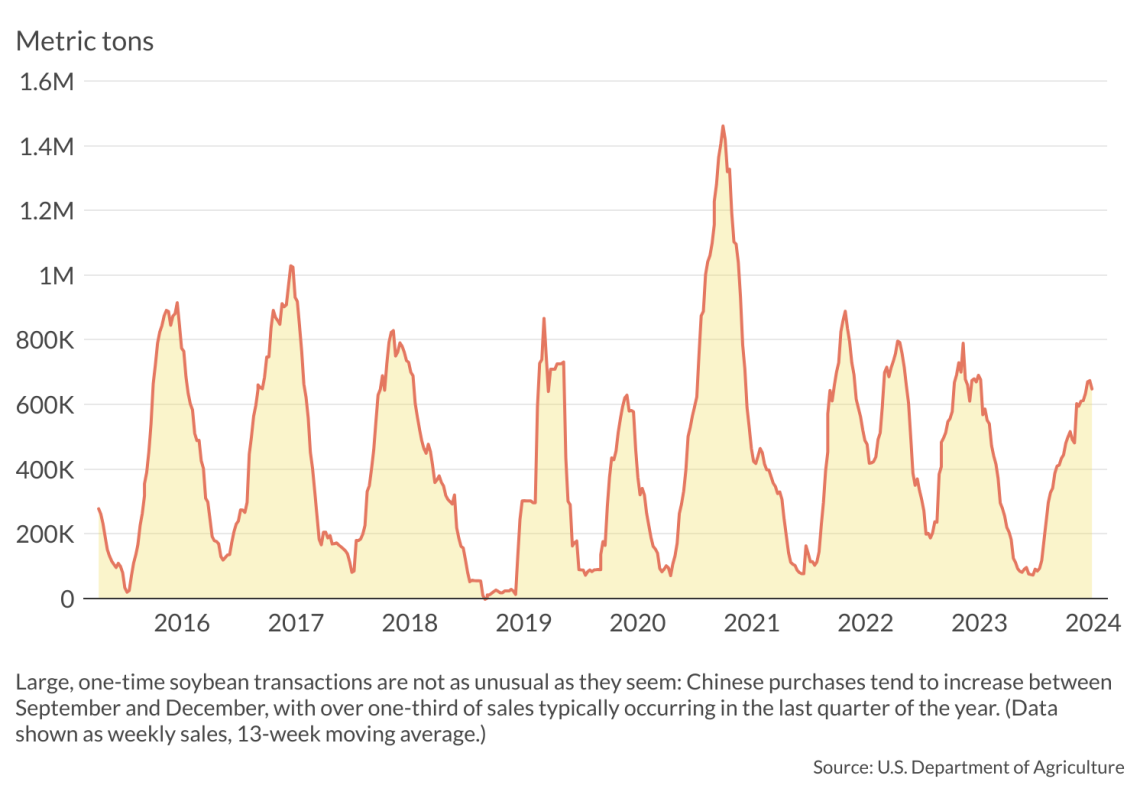

Just ahead of a November 2023 summit between United States President Joe Biden and Chinese President Xi Jinping, news broke that Beijing would buy roughly 3 million metric tons of American soybeans. According to data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the deal became the single largest weekly purchase of U.S. soybeans by Chinese buyers since a 3.9 million metric ton transaction in February 2019.

The story was covered as a possible return of “soybean diplomacy” – whereby U.S.-China tensions are eased through the sale of massive amounts of American soybeans to China. Soybeans are often at the center of trade relations between the two countries, and buying large quantities of American soybeans was a condition of the Phase One trade agreement struck in 2020.

While American and Chinese officials are indeed starting to talk more frequently again after a prolonged chill, the soybean trade may be less of a factor in bilateral relations than it seems. Chinese demand for American soybeans remains robust as Beijing’s domestic production continues to fail to meet demand. However, the recent uptick in purchases likely has less to do with geopolitics than with changes in market conditions and seasonal demand for the crop.

The status of U.S.-China relations is up for some debate, but it certainly seems calmer than during the 2018 to 2020 period, the peak of trade tensions. U.S. soybean exports to China suffered then, but they have since improved. So long as there are no significant disruptions to the relationship this year, one can expect American soybean exports to China to remain about the same as they were in 2023.

The global soybean trade

Nearly $100 billion worth of soybeans are sold around the world every year, with Brazilian and American farmers dominating global production. Of the $93.4 billion in soybeans sold in 2022, half was exported from Brazil and 37 percent from the U.S. Combined, the next largest producers – Argentina, Canada, Uruguay and Paraguay – sell only about 10 percent of global exports.

China, meanwhile, is by far the world’s largest importer of soybeans, accounting for some $61.2 billion, or 58 percent, of global imports in 2022. The second-largest buyer, the European Union, imports only 8 percent.

One problem facing China is that its demand for soybeans far outweighs its ability to produce enough at home. Of the country’s supply of 147 million tons of soybean in 2022, 69 percent was imported. Only about 13 percent was grown in China, with the rest stockpiled from the year before.

China’s soybean imports favor Brazilian sources, with roughly 60 percent coming from that country and 30 percent from the U.S. China’s large demand for soybeans, including its high ratio of imports to domestic production, is expected to continue through 2024, assuming there are no unforeseen disruptions.

Facts & figures

The impact of trade tensions

Chinese demand for American soybeans remains strong. On average, Chinese buyers purchase over 20 million metric tons of the crop every year. But these exports suffered during the U.S.-China trade tensions of 2018 to 2020: In 2018, American sales of the commodity to China were half their usual amount, falling from the 2022 figure of $18 billion all the way to $3 billion. Part of this had to do with a dip in soybean prices at the time, but geopolitics was a primary culprit.

U.S. soybean exports to China have since bounced back. However, the share of China’s soybean imports coming from America is slowly decreasing. The U.S. share of Beijing’s imports shrunk from 39 percent in 2016 to just 13 percent in 2018 as Chinese buyers sought more purchases from Brazil, and this trend is continuing today.

Similar diversification is taking place for U.S. soybean exporters. Between 2013 and 2017, 57 percent of U.S. soybean exports went to China, a share that fell to 51 percent in 2022.

Last November’s splashy, one-time purchase of some 3 million tons of U.S. soybeans might have made the headlines, but it was not that unusual considering the seasonality of soybean sales. Sales are recorded on a weekly basis by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and tend to ebb and flow throughout a given year. Chinese purchases of soybeans tend to increase significantly between September and December, with over one-third of sales typically occurring in the last quarter of the year. Other examples of large single purchases include deals for 2.3 million metric tons in September 2020, 1.5 million metric tons in September 2021 and 1.8 million metric tons in October 2022.

A sizeable one-time purchase of U.S. soybeans is also less significant given the gradual shift by Chinese buyers from American to Brazilian soybeans. In parallel, American farmers are expanding sales to markets like Mexico, Egypt and Taiwan.

U.S.-China relations under Biden

Even if the November soybean deal proves not to have had much of a meaningful effect on U.S.-China trade, what did it mean for high-level government interactions between the two powers?

The Biden-Xi relationship appears complicated. Obviously, officials in both capitals share a strong desire to maintain open diplomatic channels. But the White House continues to view China as America’s greatest security challenge. And President Joe Biden’s branding of Chinese leader Xi Jinping as a “dictator” will not be soon forgotten in Beijing.

At the same time, the relationship between Washington and Beijing has been relatively steady over the last few years – even as tariffs levied on Chinese imports during the peak of trade tensions remain in effect. President Biden and President Xi have regularly engaged one another, including in a 2021 video call, a 2022 in-person meeting in Indonesia and another in-person meeting in California last year.

Read more by Riley Walters

- Managing global supply chains in a turbulent world

- The difficulties in creating an Asian NATO

- China’s military puts Indo-Pacific on edge

Other senior government officials have also been in regular contact. In September 2023, U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen and Chinese Vice Premier He Lifeng launched two new working groups around financial and economic issues, which have already held several sessions. The two officials have agreed to speak more regularly, holding another in-person meeting just days before the Biden-Xi confab in California.

At the California summit, the two leaders exchanged their usual views on the relationship. They also announced the resumption of military-to-military communications and the establishment of a working group for counter-narcotic issues, including the scourge of fentanyl, that launched in January.

Also in January, U.S. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan met with Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi in Thailand. The visit was partly meant to foster regular communication between Washington and Beijing and to prepare for another phone call between the American and Chinese leaders.

Such diplomatic efforts between Washington and Beijing under the Biden administration have been consistent – making it unlikely that the occasional large purchase of soybeans will have much of an influence on high-level relations.

Scenarios

More likely: Stable trade

Over the last decade, soybean sales to China have only been affected by periods of increased trade tensions. During periods of stability, sales are more consistent with global demand. That means soybean sales in 2024 are likely to remain consistent with what we saw in 2023, as long as relations between Washington and Beijing continue as they have been on President Biden’s watch.

Chinese purchases of soybeans are seasonal, with demand increasing in the fall – coinciding this year with the U.S. presidential election. That means we can expect to see Chinese purchases of American soybeans increase before November’s election, but we should not attribute this rise to electoral politics.

Less likely: Political disruption

However, there is some evidence that Chinese buyers are increasing their stockpiles of soybeans – with the American product being easier to store than the Brazilian alternative. For now, this is only a slight increase. But there could be any number of factors behind it: changes in soybean prices, shifts in demand, or even uncertainty about what U.S. politics has in store.

As for the bilateral relationship, American and Chinese representatives seem likely to continue holding frequent meetings. The new working groups on finance, economics and counter-narcotics will keep high-level officials busy. Another Biden-Xi phone call has yet to materialize, but if it does happen, it may be one of the last times the two leaders speak before Washington fully enters election season this summer.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.