Beyond Russia’s war against Ukraine

With irreconcilable war aims between the combatants, the conflict will drag into 2024 and inflict more damage to the global economy and long-standing security arrangements.

In a nutshell

- The fighting in Ukraine will last through 2023, but devolve into a frozen conflict

- The economic consequences will be long-lasting and restrict globalization

- Arms control, cooperative security and nonproliferation will be weakened

Russia’s war against Ukraine will be long, brutal, devastating and exhausting. It offers little prospect of a return to lasting peace. The likely result will be an uneasy truce along a disputed and heavily armed line of demarcation: Neither peace nor war, no winners or losers, no genuine negotiations and no trust in any agreement. Stability will have to come from strong deterrence.

Ukraine wants to expel Russian forces from occupied territories. Russia wants at least to shore up its claim to the four provinces annexed in September 2022. Russia hopes that Western resolve in supporting Ukraine will erode. The United States and probably the United Kingdom will have elections in 2024, when voters could return to more malleable governments. A general election in Germany is due in 2025. Russian President Vladimir Putin faces reelection in 2024. Therefore, there will be no decisive impulse to end fighting before 2024.

The war aims of the combatants are irreconcilable. Both sides will refuse to negotiate until they are convinced that military operations cannot improve their leverage. There is no common ground, no confidence and no spirit of compromise after Russia’s atrocities and its ruthless campaign of targeting civilian infrastructure.

The frontline battles will determine the outcome of negotiations. As the war grinds on, human, economic and financial resources will be crucial. A war of attrition is decided by the exhaustion of one party. Attrition is a matter of perseverance, collective willpower and individual morale. Ukraine faces greater material losses, while the loss of morale and political willpower could be a major threat to Russia.

Neither side can subjugate the other. Even if Ukraine were to give up territory, this would not lead to peace if Russia remains focused on eliminating supposed “Nazis,” demilitarizing Ukraine and peddling the myth of the smaller brother that has no claim to its own national identity or political independence.

This war is not only about Ukraine’s territory or governance. It is about Russia’s future, about a sense of its historical mission and its combination of jingoistic arrogance and paranoid victimization. Without a fundamental change in the Russian mentality, prospects for cooperation will remain elusive. President Putin has turned a “brother nation” into a hostile neighbor, full of suspicion, hatred and painful memories.

The bloodlands are bleeding again. The barbarous cruelty of the Kremlin’s soldiers recalls the worst images of World War I trench warfare in Flanders and of the inhuman atrocities of the Holodomor and the Holocaust.

The damage to Ukraine will be overcome with international assistance. The destruction of an antiquated Soviet infrastructure could turn into a blessing in disguise, presenting Ukraine with a chance of building a modern, competitive and environmentally friendly economy. Once the fighting is over, Ukraine could experience an economic miracle. Wartime destruction could evolve into peacetime modernization. Russia, on the other hand, is bound to progressively feel the full impact of economic and financial sanctions. Sanctions do not work like a heart attack; their effect is more like a slowly spreading cancer. Tackling long-term harm will prove more difficult. They will include fundamental shifts in trade patterns and geopolitical power relations.

Read a related report

The Russian economy mobilizes for war

Economic consequences

The dream that economic actors are rational individuals interested only in profits, efficiency and growth has been decisively shattered. Security, vulnerability and politically dictated strategic goals have become determining factors in economic equations. Political priorities are reasserting their primacy over economic calculations. Business leaders will pay more attention to geopolitical risks and opportunities as deep fault lines permeate the globalized world.

Supply chains

Supply chains are now reevaluated in terms of political threats. Ever since the oil shock of 1973, the world has had ample time to learn that supply lines convey political leverage. This applies not only to energy. It covers food, pharmaceuticals, computer chips (and the machines that make them) and components for batteries and smartphones (copper, nickel, cobalt, lithium and rare earths). The threat of politically denied access and the interruption of trade links are new risks. They can be mitigated through diversification and reshoring. But both approaches raise costs.

Protectionism

A return to protectionism is looming, at least in strategically important sectors. Protecting competitive edges in advanced technologies will become a dominant concern for governments. Securing the availability of vital inputs and protecting intellectual property rights will play a much greater role.

Protectionism is the instrumentalization of economic and financial leverage to achieve political ends. Most nations are presently subject to some sort of sanctions. Even the European Union and the U.S. have imposed mutual sanctions. Sanctions can inflict economic costs, yet their political impact remains highly doubtful. Tariffs and quotas, export controls and diversification of imports will work against free trade. The future will see a consolidation of privileged trade areas along political lines.

Economic affairs are becoming more politicized.

Subsidies

State interventions will become common and accepted. Most countries have resorted to generous subsidies during the Covid-19 crisis. Massive state aid has been doled out to cushion the effect of energy spikes and inflationary pressures. Looming climate change is adding to the temptation for governments to impose industrial policies. State planning is returning through the back door. Decisions on energy mixes, price ceilings and minimum wages, price tags on emissions, standards on car exhausts, housing insulation and heating technologies as well as environmental standards require political guidance and incentives – in other words, subsidies. Economic affairs are becoming more politicized. Business managers will have to devote much more attention to geopolitical risks and politically decided economic strategies.

Inflation

Inflationary pressures will stay high. Inflation is close to double-digit figures. In the U.S., it is around 8 percent, in the European Union close to 10 percent, but with a significant spread: in Estonia, it is above 20 percent, in Ireland and non-EU Switzerland it remains below 2.5 percent.

Energy prices may have been a decisive factor. But it would be premature to assume that a return of energy prices to normal would bring inflation down to precrisis levels. There are other factors contributing to inflation: food (including fertilizers), electric and electronic appliances, reshoring, protectionism, services (reflecting a global shortage of qualified workers) and climate change.

Inflationary pressures are only now starting to translate into demands for wage increases. Inflation will stay somewhere between 4 percent and 8 percent. Central banks are loath to raise interest rates since higher ones could cause trouble for governments. Italy and Greece spend more than 8 percent of government expenditures on debt servicing. If interest rates were to be sufficiently raised to force inflation back to 2 percent, both countries might have to spend about 20 percent of their budgets on debt servicing.

Facts & figures

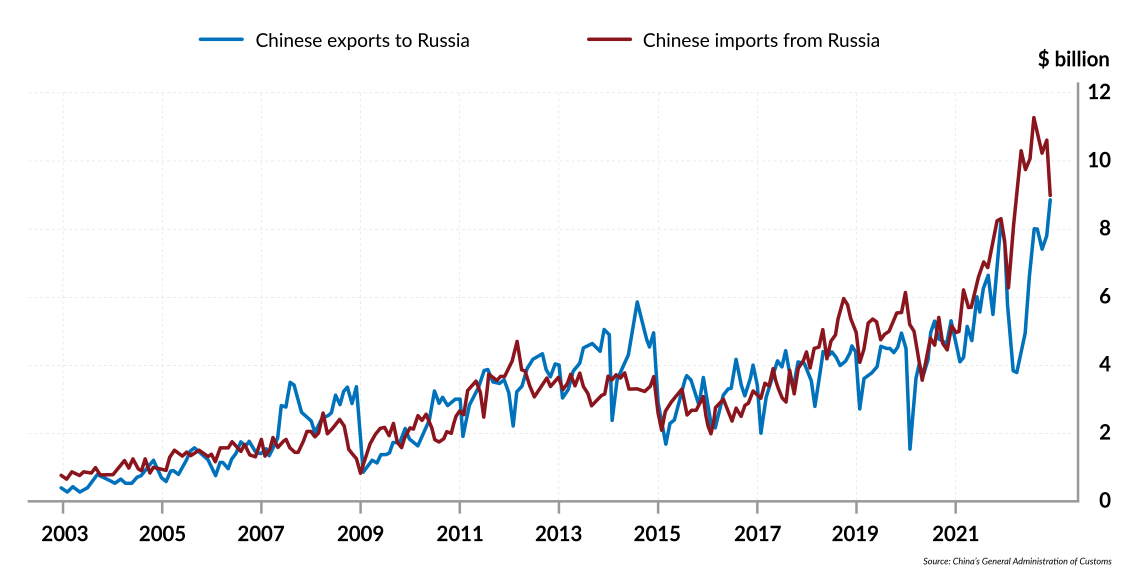

China capitalizes on war to boost trade with Russia

Geopolitical consequences

The geopolitical distribution of power will see a fundamental shift. Traditional political alignments will harden. The world will remain divided into three groups that face each other with suspicion and open hostility:

- Western liberal democracies (U.S., Canada, EU, UK, Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand)

- Russia, Belarus, Iran, Syria, Venezuela and North Korea, with China staying close. Regimes in these countries despise legal constraints both in dealing with other international actors or with their own subjects

- Developing nations of the South Asian subcontinent, the Arab world and South America

International institutions like the United Nations or the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) are paralyzed; regional associations will gather strength. Pressure for reform of the Security Council will rise but will have even lesser chances of success than 20 years ago.

The main beneficiaries of Russia’s war are China, India, Turkey, Iran and North Korea. They exploit trade opportunities that Western sanctions open for them. They profit from Russian oil at discount prices.

China’s bilateral trade with Russia grew to a record $190 billion in 2022, comparable to its trade with Germany. Last year’s China-U.S. trade, meanwhile, also grew to a record $691 billion. Chinese exports of finished industrial products rose by almost 40 percent. China (and to a lesser extent Turkey, India and Iran) serve as a convenient conduit for illegal transactions helping Russia to circumvent sanctions. Russia’s protracted war on its western front presents additional opportunities for China to improve its position vis-a-vis Russia’s Far East. China profits most as the two superpowers weaken each other and U.S. attention is diverted from the Pacific to the Atlantic.

India has been quick in buying cheap Russian fuel and in benefitting from supplying what Moscow can no longer obtain directly from the West.

Turkey is mediating in this war. Communication channels with both sides remain open. Russia’s entanglement in Ukraine has strengthened Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s hand in Syria. Turkey is the only NATO country that has shot down a Russian combat aircraft (in 2015) and is enjoying a privileged position vis-a-vis Moscow, having bought the Russian air defense system S-400 and having its first nuclear power station built by Rosatom.

The experience of Ukraine sends a message to the rest of the world: If you have nuclear weapons, never give them up. If you do not have them, spare no efforts in obtaining them.

Iran and North Korea have assumed a crucial role in weapon supplies. Russia is bound to honor their support at a critical juncture with political (and perhaps technological) support.

Oil-exporting Arab states will see their political influence strengthened in the short term. In the long run, they expect their influence to wane as a sustained turn to renewables will undermine their position as oligopolists of fossil fuels – a strong argument to maximize exploitation of their bargaining power as long as they still have it. OPEC’s recent decision not to expand oil production despite a formal U.S. request is a harbinger of things to come.

The energy crunch will accelerate a renaissance of nuclear power, with Russia, China, France and the U.S. as leading nations in building and servicing nuclear power plants.

Arms control and cooperative security

The war weakens nonproliferation. In 1991, Ukraine inherited a huge inventory of nuclear weapons after the Soviet Union’s demise. It handed them over to Russia in return for assurances of its territorial integrity and of the inviolability of its borders (1994 Budapest Memorandum). Three years later, Russia reaffirmed these obligations in the 1997 Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation. Specifically, the treaty stipulated that neither side would invade or declare war on the other. President Putin’s repeated nuclear threats have undermined assurances of no first use and the traditional role of nuclear weapons as a last resort in case of national survival.

The experience of Ukraine sends a message to the rest of the world: If you have nuclear weapons, never give them up. If you do not have them, spare no efforts in obtaining them.

This lesson will not be lost on Iran, Turkey and Arab and East Asian countries that have reason to doubt the U.S. nuclear commitment. South Korea is already openly musing about acquiring nuclear weapons. Like Japan, it would probably take less than two years to produce them. China and North Korea are expanding their nuclear arsenals; China in the hope of matching the arsenals of the nuclear superpowers, North Korea with the aim of developing a deterrence of a size somewhere between Pakistan and the UK.

The 21st century could become the century of rampant proliferation with more than 15 nuclear weapons states at the turn of the next century. If the war against Ukraine ends in a bitter standoff between Kyiv and Moscow, Ukraine must be fully included within the Western defense parameter, with NATO probably redeploying the bulk of its forces further east. Otherwise, Ukraine might feel impelled to go nuclear itself. The happy days of cooperative security are gone, and they are unlikely to return for a long time.

President Putin’s war against Ukraine has destroyed chances for agreements on arms control, disarmament and transparency. Russia has dropped out of the Council of Europe and of the European Court for Human Rights. Mr. Putin has put his country on a confrontational and belligerent trajectory. It will take years of painstaking, delicate and sober diplomacy to help Russia out of its present dead end.