Peacekeeping without the UN

A new African security architecture is emerging in the wake of the United Nations’ peacekeeping failures.

In a nutshell

- UN peacekeeping missions have mostly failed to stabilize Africa

- Many African governments are considering alternative security options

- Private companies and regional forces will likely gain prominence

Since its inception in 1948, the modern concept of peacekeeping has been a cornerstone of the international liberal order. At the end of the Cold War, peacekeeping gained new momentum, embracing a broader human security framework, in line with the post-Westphalian model.

This new approach reflected the United Nations’ growing ambitions and its expanding framework. The UN Security Council began to authorize “second-generation” peace operations to not only monitor cease-fire agreements but also tackle the underlying causes of conflicts through “peacebuilding.” However, in Africa, UN multidimensional missions have struggled to achieve their goals, stoking increasing resentment among local populations.

Changing security landscape

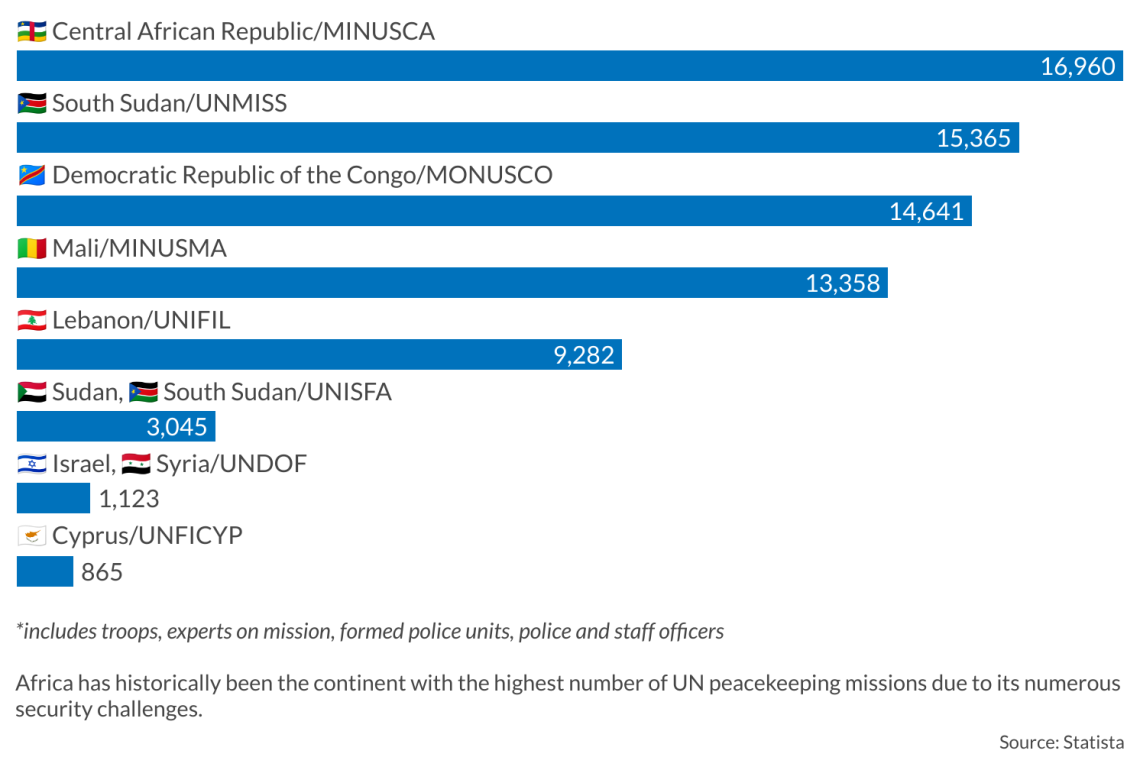

Amid shifts in global geopolitical dynamics, the future of peacebuilding is increasingly influenced by developments in Africa – where over 80 percent of the 90,000 UN field personnel is deployed. There have been 13 African UN missions since 2000. The continent hosts four of the largest UN operations, which together command most of the $6.1 billion budget allocated for the 2023-2024 fiscal year.

The security landscape of the continent has changed substantially in the past 15 years. The fragmentation of Libya following Muammar Qaddafi’s fall precipitated instability across the Sahel region. The 2023 Global Terrorism Index highlights a dramatic surge in terrorist attack fatalities in the Sahel, with an increase of over 2,000 percent since 2008. Jihadism has also spread in both Western and Eastern Africa.

More recently, there has been an increase in military coups in West Africa and the Sahel. Civil war broke out in Ethiopia (where a peace process is now under way) and Sudan. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the east of the country remains ravaged by violence.

The UN’s struggle to effectively tackle these developments has led to backlash against peacekeeping operations. In July 2023, the government of Mali requested that the UN Security Council terminate the UN stabilization mission in the country. And in September, recently reelected Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) President Felix Tshisekedi asked for an anticipated and “accelerated” withdrawal of the United Nations stabilization mission in his country, referred to as MONUSCO.

Major UN peacekeeping failures

Since its early days, the history of post-Cold War peace operations in Africa is marked by some successes (Liberia, for example) and several failures. Among the most dramatic was Rwanda in 1994, when UN troops failed to prevent the genocide against the Tutsis, and 800,000 Rwandans were killed.

Mali. The United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) was established in 2013 following a coup in 2012 and the emergence of separatist rebel movements in the north. After two additional coups in 2021 and 2022, and following the withdrawal of the French Operation Barkhane and the European Union’s Takuba Task Force, MINUSMA forces left the country in April 2023. Meanwhile, the Wagner group, a Russian private military company, has become a significant security presence on the ground, leaving Mali in a precarious position.

Amid continuous clashes involving the military, jihadist factions and separatists, there have been numerous protests against the UN in Bamako. Critics have accused MINUSMA of failing to safeguard civilians, and the ruling military junta has argued that UN forces have exacerbated local tensions, becoming part of the problem. The departure of MINUSMA, one of the most funded UN missions with a 13,000-strong force, is anticipated to result in financial shortfalls for other ongoing missions, further complicating the peacekeeping landscape in Africa.

Facts & figures

Democratic Republic of the Congo. In the DRC, UN peacekeeping has been present since 1999. In 2022, there were several violent protests against MONUSCO, leading to casualties among civilians and UN personnel. Protesters accused the mission of failing to protect the population, as several armed groups still carry out violent attacks in eastern Congo. Recently, the UN and the DRC reached an agreement for the withdrawal of MONUSCO. Two regional coalition forces – one led by the East African Community and the other by the South African Development Company – will remain active.

Central African Republic. The UN also has a multidimensional integrated stabilization mission in the Central African Republic. MINUSCA, as it is known, was deployed in 2014 and has more than 17,000 uniformed personnel. After a period of improvement, the country’s security outlook started to deteriorate in 2017 due to rising violence and political fragmentation.

Since 2018, Russia has been supporting President Faustin-Archange Touadera in his effort to regain control of territory lost to rebel groups. The president’s security is guaranteed by members of the Wagner group, who in exchange for training the army were granted access to mines under state control. Rwanda, the main contributor of troops to MINUSCA, has also signed a bilateral agreement with the government to deploy additional troops. Like in the DRC and in Mali, there were violent popular protests against MINUSCA. The UN Security Council renewed the MINUSCA mandate until November 2024.

Alternative security approaches

Large-scale peacekeeping operations are complex and require significant funding from several stakeholders. For countries that contribute troops, the missions offer a chance to receive financial support, boost their regional and international influence and enhance their military capabilities.

One of the unintended effects, however, is corruption, which can occur in various spheres of activities – for example in contracting mission personnel, or through privileged access to natural resources. In 2008, UN troops in the DRC were accused of trading gold and arms with rebel groups. Peacekeeping personnel and humanitarian workers in Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone, the Central African Republic and the DRC have also been accused of sexual abuse and exploitation of civilians, including refugees.

Besides the challenges posed by the recent wave of instability in Africa, the future of peacekeeping operations on the continent is also dependent on the evolution of the international system. The UN system is struggling to adapt to a more fragmented international order. The war in Ukraine and the conflict between Israel and Hamas have highlighted the organization’s limits; the decision process is paralyzed by opposing views in the Security Council and its operational capacity is hampered by an expanding bureaucracy.

More on UN peacekeeping

Peacekeeping sunset

The future of MONUSCO

At the same time, China has consolidated its role as a key player in several UN agencies. Previously doubtful about the value of peacekeeping operations, China has shifted its stance to become the second-largest financial contributor to the United Nations’ budget and peacekeeping efforts. Additionally, it is now the foremost troop contributor among Security Council members.

In contrast to the approach of Western liberal democracies, China has focused on the principles of sovereignty and impartiality. Echoing the wishes expressed by several African countries, Beijing has called for African actors to lead security efforts on the continent. Faced with funding shortages and the systematic failure of multidimensional and ambitious UN-led missions, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres has also expressed support for this alternative approach, under which the African Union or regional bodies oversee peace and stabilization initiatives. Under this model, the number of peace operations has increased over the past decade, with mixed results.

Scenarios

The UN is facing multiple challenges. The Security Council does not reflect the balance of power in the international system. The organization is under mounting pressure to fulfill an increasingly ambitious, if vague, agenda through a large, inefficient bureaucratic structure. By and large, UN forces have not solved security issues in Africa.

These shortcomings have led to escalating skepticism. In the Middle East, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) has come under fire for its alleged support for Hamas. Four out of the five permanent members of the Security Council did not participate in the UNGA annual meeting which took place last September in New York. Moreover, as the operational costs of peacekeeping operations increase (especially costs with civilian personnel), states seem less willing to pay for them.

Considering this, two main scenarios should be considered.

Somewhat likely: Regional multilateral agreements

Under a first scenario, UN-led multidimensional missions in Africa are gradually replaced by regional frameworks under the leadership of the African Union or regional organizations. However, these will remain dependent on UN financing since most African countries are not able or willing to pay for their cost. This alternative approach would be justified on the grounds that challenges to security in Africa – which are directly or indirectly connected to refugee and migrant flows, organized crime, terrorism and piracy – constitute challenges to global security.

Under this scenario, countries like Rwanda, which have both the will and the capacity to provide security support, will gain additional leverage. In the long term, the rise of China in the UN system will likely lead to substantial changes in the principles of peacekeeping.

More likely: Bilateral agreements with a broad range of security actors

Under a second, slightly more likely scenario, the security architecture in Africa will see several new actors, like paramilitary groups, private security companies or states acting under bilateral – rather than multilateral – agreements.

Two main factors suggest that this may be the most likely scenario. First, the decision-making body within the UN – the Security Council – is expected to become more ineffective. There seems to be no alternative to the current status quo, especially considering the current challenges to multilateralism.

Second, if Donald Trump returns to the White House, the UN will face additional funding and political challenges. A Trump administration would – perhaps even more than in 2016-2020 – cut UN financing and withdraw U.S. support for global initiatives. Under this scenario, UN peacekeeping would face additional cash shortfalls. Bilateral agreements with great or regional powers and non-state actors would then fill the security vacuum in Africa.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.