India’s stake in the Afghanistan conflict

India is happy that the United States has recommitted to fighting the Taliban in Afghanistan. Keeping them out of power will limit the influence of India’s longtime rival, Pakistan. But the U.S. commitment is tenuous, and President Donald Trump is a known skeptic of the war.

In a nutshell

- India wants to limit Pakistan’s influence in Afghanistan

- A continued U.S. military presence there is uncertain

- Russia and Iran are using the Taliban to undermine the U.S.

- India will continue to support the Kabul government through nonmilitary means

India’s government was among those most pleased when United States President Donald Trump announced in August last year that his country was recommitting itself to fighting the Taliban in Afghanistan. Preventing the restoration of Taliban rule in Kabul has been the cornerstone of India’s Afghanistan policy for the past 16 years. Its unspoken goal is reducing the influence of Pakistan, India’s regional rival and the Taliban’s main external supporter.

However, the latest chapter in Afghanistan’s ongoing conflict is geopolitically fuzzier than before. The U.S. military commitment to Afghanistan remains weak – President Trump is the leading skeptic in his administration. Iran and Russia, because of their problems with the U.S., have moved closer to the Taliban. While Washington has publicly urged New Delhi to do more to support the regime in Kabul, it will only do so through nonmilitary means. The shifting sands on which the geopolitical game in Afghanistan is being played have moved in India’s favor. Nevertheless, New Delhi is assuming this is a short-term development, and will limit its Afghan role accordingly.

India

New Delhi believes the original Taliban regime helped Pakistan sustain the surge in Kashmiri secessionist violence that troubled India in the 1990s and cheered when the U.S. drove the Taliban from Kabul in 2001. It has since repeatedly called for a “united, sovereign Afghanistan,” defined as a Kabul-based government without the Taliban and, therefore, Pakistani influence.

Yet India’s influence in Afghanistan after 2001 has been greatly limited. The U.S.’s geographical dependence on Pakistan for its military operations in Afghanistan gave Islamabad a de facto veto over the scope of Indian activities. India contented itself with launching its largest-ever foreign aid program in Afghanistan. It also developed strong personal relationships with various Afghan leaders, most notably former President Hamid Karzai (2004-2014), in part because of their problems with Pakistan and its support for the Taliban.

Indian officials accepted that what they did in Afghanistan was at the forbearance of the U.S. They trimmed their policy sails according to Washington’s mood, resisting only the idea of political reconciliation with the Taliban. A senior Indian diplomat who oversaw Afghan affairs for years said that in Afghanistan, “it is largely true to say India reacts to conditions created by external players.”

While India’s political fortunes in Afghanistan fluctuated, it remained extremely popular among the Afghan public. Opinion polls consistently showed India earning approval ratings of 75 to 85 percent with Afghans, well above any other country. Many Afghan leaders keep their families in New Delhi and even the Taliban has publicly said it has nothing against India.

It is largely true to say that in Afghanistan, India reacts to conditions created by external players.

Under President Barack Obama, reconciliation with the Taliban and eventual U.S. military withdrawal took center stage. This meant wooing Islamabad and sidelining New Delhi. By 2010, India was not even invited to the annual international conference on Afghanistan. India reluctantly endorsed reconciliation but asked that it be “Afghan-owned and Afghan-led” – code for minimizing Pakistan’s say in the process. As the U.S. began winding down its military presence, India increased support for Kabul. India shipped four Russian-made helicopter gunships to the Afghan government in 2015, the first time India had provided lethal weapons to Kabul.

Trump

India’s plans to increase its military involvement have been put on hold thanks to the Trump administration’s announcement that it would send 3,000 U.S. soldiers and commit large amounts of air power to support the Afghan army. President Trump did not abandon reconciliation with the Taliban, but did insist that Kabul should hold talks from a position of strength. India was especially impressed by the U.S. president’s strong denunciation of Pakistan. In an August 2017 speech, Mr. Trump accused Pakistan of “sheltering” the Taliban and demanded this policy “change immediately.” He also invited India to play a larger role in Afghanistan.

A few weeks after that speech, U.S. Defense Secretary James Mattis traveled to New Delhi. Secretary Mattis told the Indian government that Washington did not expect or want Indian troops in Afghanistan. India was asked to do more of what it was already doing: development assistance, diplomatic support and military training. Afghanistan informed India that, given the U.S.’s plans on the air power front, more helicopters from India would no longer be needed. Secretary Mattis underlined that the U.S. depended on the port in Karachi for only about 17 percent of its logistics needs. In Washington’s new Afghan policy, Pakistan would be treated as an adversary rather than an ally.

Russia, China and Iran

The complication New Delhi faces in Afghanistan is Washington’s deteriorating relations with Moscow and Tehran, both of whom are angry about American economic sanctions. Afghanistan is becoming a proxy for their desire to inflict pain on the U.S.

Russia has given up its Pakistan card, but not its Afghan bet.

According to Indian, Afghan and American sources, Russia is now supplying weapons to the Taliban. Moscow has also begun expanding its military relations with Pakistan. Indian officials say Russia is “obsessed” with a desire to undermine the U.S. This introduced tensions in the Indo-Russian relationship, where differences had recently been patched up. Russia has given up its Pakistan card, but not its Afghan bet.

Iran has flirted with the Taliban in previous attempts to drive the U.S. out of Afghanistan. Nonetheless, it nearly went to war with the original Taliban regime and has testy relations with Pakistan. For now, its anger over what it sees as U.S. backtracking on sanctions has trumped its dislike for the Taliban. General John W. Nicholson Jr., commander of the Resolute Support Mission in Afghanistan, told Indian audiences late last year that his three primary foreign concerns were “Pakistan, Russia and Iran.”

China, Pakistan’s closest international partner, emerged as the last major advocate of a negotiated Afghan settlement with all regional players, including India. China has sponsored or proposed several regional and bilateral agreements on Afghanistan, some of them including India, from 2006 onward. Beijing fears continued fighting in Afghanistan will endanger its nearby Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects and terrorist spillover from Afghanistan would enter its Muslim-dominated provinces. With the U.S. gearing up for another round of conflict, China has since fallen silent.

Scenarios

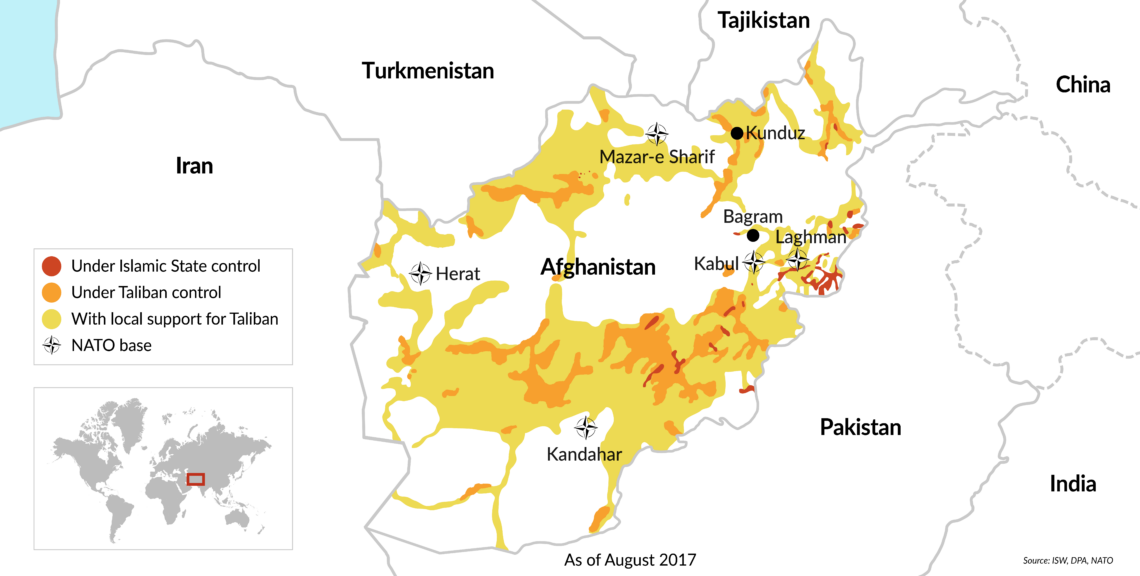

The key factor for Afghanistan’s future, and therefore for India’s policy, is the U.S. military effort over the next two years. The Trump administration’s goal is to bring 80 percent of Afghanistan under Kabul’s control by the end of 2019. It will also begin providing helicopter gunships and deploying drones to support the Afghan army while increasing the American troop presence to 16,000. The first military test will be the next Taliban spring offensive. Politically, the U.S. wants to help Afghanistan hold parliamentary and presidential elections this year and hope they produce a stable Kabul government. Then there is the question of President Trump’s own political future, though he seems to have handed Afghan policy to a trio of generals (including Mr. Mattis) who handle much of his foreign and security policy.

The most likely scenario is a round of fierce fighting as the Taliban seek to shake the Kabul government before the U.S. military buildup picks up steam. Though senior Afghan leaders express apprehension about President Trump keeping his promises, the first U.S. troop deployments have already commenced. It is unlikely much will come of Taliban reconciliation efforts as all sides will wait to see the results on the battlefield. The political landscape will also be uncertain as elections in Afghanistan, Pakistan and even the U.S. will take place this year. The external players are already adjusting their stances: Pakistan distancing itself from the Taliban, India coming out more in favor of Kabul, and China waiting to see how successful the U.S. will be.

The most important variable will be the Trump administration’s stance. A surge in U.S. casualties or costs next year could see the president override his advisors and demand a rollback. This would put American policy back into reverse gear and embolden the Taliban and Pakistan. The political character of the fighting would change: the purpose would be to determine how long it would take for the Taliban to be able to dictate terms.

The most unlikely scenario would be a sweeping U.S. military victory over the Taliban, forcing them into talks on Kabul’s terms. Whatever the outcome, India will attempt to reduce Afghanistan’s dependency on Pakistan by pursuing its construction of a container route through the Iranian port of Chabahar into northwest Afghanistan and developing Afghanistan’s largely untapped hydroelectric potential. New Delhi has also begun undermining Kabul’s earlier support for China’s BRI plans as part of a separate geopolitical game.