New Delhi contends with the Taliban regime

India expected a gradual departure of the US military from Afghanistan, and the rapid exit initially appeared like a serious setback. But the Taliban regime’s isolation on the world stage and its economic woes have made it less likely that they will pose a serious threat to India.

In a nutshell

- Taliban rule is a security concern for New Delhi

- The new Afghan leaders face serious difficulties

- India hopes a lack of allies will hamstring Kabul

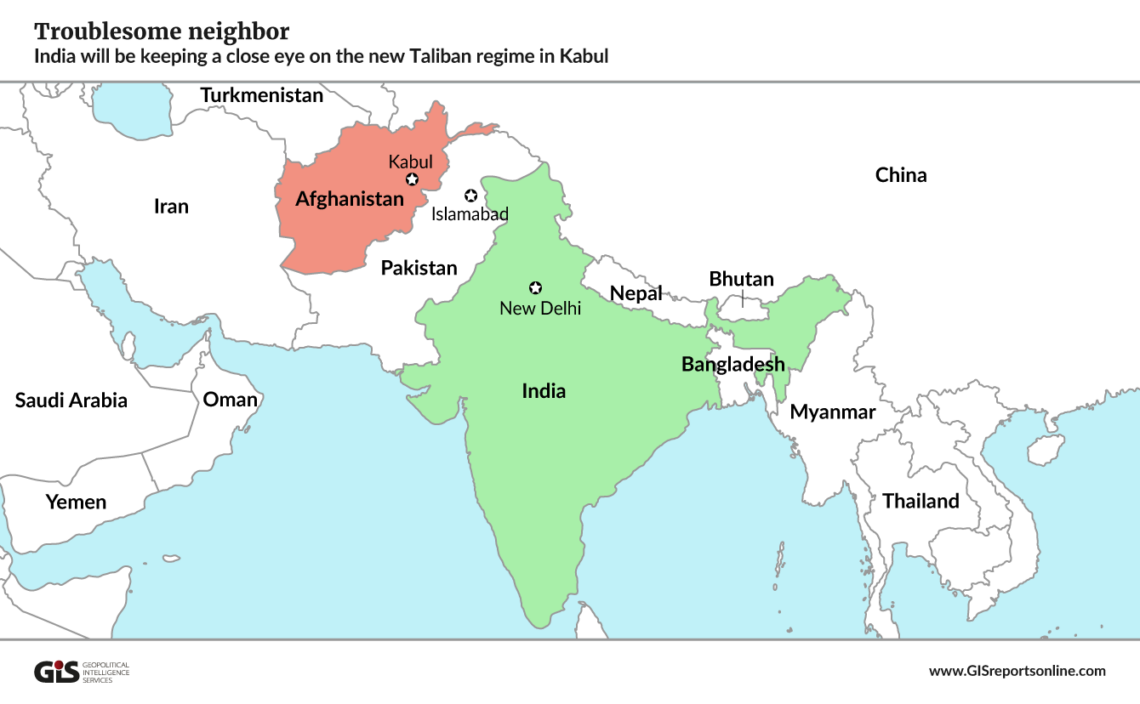

Like most governments, India was caught by surprise at the speed with which the Taliban recaptured Afghanistan. The new regime is dominated by the faction closest to the Pakistani military and has declared its desire to build a fruitful relationship with China. New Delhi initially accepted that it had suffered a major strategic setback. Three months later, the country is cautiously optimistic the fallout will be manageable.

International appetite for recognizing the Taliban regime is minimal. Concerns that Kabul’s fall would sharply skew the regional security balance in Pakistan’s favor have proven unfounded. But India accepts the present uncertainty in Southwest and Central Asia means it will have to invest more diplomatic resources in the region than it has in the recent past.

The U.S. withdrawal

Over the past decade, successive Indian governments had braced themselves for a withdrawal of the United States military from Afghanistan. In the wider neighborhood, India was almost alone in supporting U.S. military presence and the Afghan democratic polity. From 1992 onward, New Delhi spent $3 billion on Afghan assistance, its largest aid program ever. For several years, it quietly deployed several thousand paramilitary troops and provided arms and training to the Afghan National Army. All of this was underpinned by a geopolitical desire to minimize Pakistani influence in Afghanistan, and an awareness that the most violent years of the insurgency in Indian Kashmir coincided with the first Taliban regime.

India’s policy in the short run is to isolate the Taliban.

India had assumed a phased U.S. departure followed by years of bloody stalemate between Kabul and the Taliban. In expectation of increased violence, it began evacuating its nationals, along with Afghan Sikhs and Hindus, starting in late 2020. Only a few hundred citizens still had to fly out when the Taliban took over.

After it closed its embassy, India announced an electronic visa program for Afghans who wished to leave. But between Afghan preference for emigration to the West and the Modi government’s worries about Islamic terrorism, only a few hundred such visas were issued. More usefully, the 14,000 Afghans studying in India were given stay extensions and limited work rights.

Isolating the Taliban

India’s policy in the short run is to isolate the Taliban, make Afghanistan an economic migraine for its new external patrons and hope to persuade the new rulers not to support resident terrorist groups like Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammed, which target India. Knowing it has few aces to play when it comes to the Taliban, New Delhi has sought to capitalize on the concerns of various regional and international players.

The Taliban’s strongest supporters are Pakistan, China and Qatar. Pakistan was initially ecstatic. Other than defeating India, overthrowing the Kabul regime was its foremost strategic desire. However, Taliban infighting, international recognition problems and a slow-motion Afghan economic collapse have made Islamabad more subdued. China has also wooed the Taliban, positioning itself as their natural economic partner and diplomatic patron going forward. But the Taliban’s refusal to act against resident Uighur militants has tested Beijing’s patience. Qatar is quieter in its support for the Taliban but has a preference for a different set of factions. All of them have pulled their hair out about the Taliban’s unwillingness to modify their domestic behavior to secure international support.

Facts & figures

India also belongs to a loose coalition of foreign governments set on forcing the Taliban to suppress the estimated 5,000 to 7,000 terrorists living in Afghan territory. Iran and Russia, who worked hard to push out the U.S., have reached out to others to pressure the Taliban on this issue. The Central Asian republics that, like India, have been past recipients of Taliban-exported terrorism have been the most alarmed. Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, two countries that recognized the original Taliban regime, have publicly declared opposition to its present incarnation.

The West wavers on whether engagement or isolation is the best means to influence the Taliban on a range of issues that include terrorism, refugees and women’s education. The U.S. has signaled that it has washed its hands of the country, no matter the consequences. It is prepared to engage with the Taliban at some point, but only for the purposes of suppressing al-Qaeda and Islamic State fighters based in Afghanistan and, secondarily, reducing Russian and Iranian influence. European interests are more heavily weighted in favor of humanitarian and refugee issues, and governments assume engagement will be inevitable. The United Kingdom is particularly vocal in arguing against isolation.

India’s attempts at isolating the regime receive their greatest assistance from the Taliban themselves. The Haqqani faction of the Taliban, extremely conservative and joined at the hip to the Pakistani military, marginalized the leaders who had negotiated the U.S. withdrawal. The imposition of a medieval-style Islamic rule has made it difficult for any government to support them. Most damaging has been the Taliban’s inclination to view most Islamic fighters as brothers in arms. Even Islamabad has failed to get the Taliban to change their view. The Taliban have been reluctant to act against an affiliate, the Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan, which has begun carrying out attacks against Islamabad.

Scenarios

India is not unhappy with the present state of affairs. The Taliban are isolated and bankrupt. Pakistan and China face the prospect of having to financially and politically support a difficult and expensive international pariah. The Taliban have shown little coalition-building skills. Petty intimidation and repeated acts of domestic terrorism indicate a weakness of central authority. The economy is imploding without the huge injections of U.S. funds to which it was used. The passage of UN Security Council Resolution 2593 under India’s chairmanship is a further barrier as it ties recognition to human rights and security requirements that the Taliban will find hard to fulfill.

The Taliban have not been overly hostile to India. While they have made cursory comments about Kashmir, they have been eager for New Delhi to resume trade relations and wish to take up a long-standing and potentially lucrative gas pipeline project connecting Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India. India has seen an uptick in violence in Kashmir, but this is more about an emboldened Pakistan than any tangible link to the Taliban. An Afghanistan steadily sliding into humanitarian and political chaos would pin down Pakistan as much as the U.S. military did. But this present limbo is unlikely to last.

The most unlikely development would be what the Taliban hope to see: full-fledged international recognition without strings attached. The West could yet buckle as the humanitarian crisis that will take place this winter unfolds. The Taliban have waved other sticks, including increased opium production and refugees. But with the United Nations, the G20 and other conclaves insisting on conditionalities like women’s education and tough action on terrorism, recognition will remain a tortuous road. Notably, neither Pakistan nor China have extended full recognition, largely over the terrorism issue.

In the next few years, assuming the Taliban do not fall apart from internal fissures, New Delhi believes there will be a slow shift in much of the international community to some form of engagement. To woo the West, the Taliban are expected to make symbolic improvements on women’s rights and take more substantive action when it comes to opium production and refugees.

The thorniest issue will be terrorism. The Taliban will probably seek to split the international community. Washington will be offered the neutralization of al-Qaeda and the Islamic State (also known as ISIS or Daesh). No action will be taken against groups that target India, Iran or Central Asia. A similar sliding scale of recognition would probably see China, Pakistan, Russia, Qatar and Turkey move first and the Western governments coming through next. It will be the other neighbors – Iran and Central Asia – that will prove the most recalcitrant about accepting the Taliban.

It is these latter governments that India will court the most. For its part, New Delhi will adopt a simple policy in regard to terrorism with Afghan characteristics. Since Pakistan is the Taliban’s primary sponsor, Islamabad will be held responsible for any terror atrocity. New Delhi has already sent a reminder that a standing policy of punitive military retaliation remains in place.