U.S. economy awaits the next moves by Powell and Trump

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell worries that trade dispute with China is harming the U.S. economy, and President Donald Trump believes a more aggressive monetary policy is necessary. Both men want to burnish their image and consolidate their power.

In a nutshell

- President Trump wants a more active monetary policy

- Fed Chairman Powell blames slow growth on the trade dispute

- The Fed may act more aggressively, despite the economic risks

- The key factor is whether a trade deal with China gets done

In recent reports, we have maintained that the global economic situation is characterized by features that are going to last for several years: slow growth in Europe, moderate growth in the United States and some sort of soft landing in China. There will be critical moments, but the long-term trend is clear. Monetary policies will depend on how policymakers react to that trend. It is apparent, however, that today’s monetary policy hardly influences the real economy. Rather than enhancing production, it redistributes wealth. For example, artificially low interest rates transform savings into subsidies to ailing companies and highly indebted governments.

The lesson that should have been drawn is simple. Economic performance will remain disappointing as long as policymakers keep tampering with the market and believe that they can fix the very problems they are creating by managing aggregate demand and feeding public expenditure. Indeed, over the past 50 years, Western economies have been living through a miracle that went almost unnoticed: technological progress has allowed them to grow despite policies that have done very little to promote competition and entrepreneurship.

Economic performance will remain disappointing as long as policymakers keep tampering with the market.

Policymakers seem to have drawn a different, self-serving conclusion. As long as technology compensates for the inefficiencies of heavy taxation and big government, they trust they will find little opposition to expanding their role and using the economy to enhance their power and prestige. This megalomaniac approach is an increasingly distinctive feature of American politics, with some followers in Western Europe as well, including in Italy and the United Kingdom. August 2019 offered some examples of what this means in the case of the U.S. and provided clues with regard to what we may expect in the next few months.

Blame game

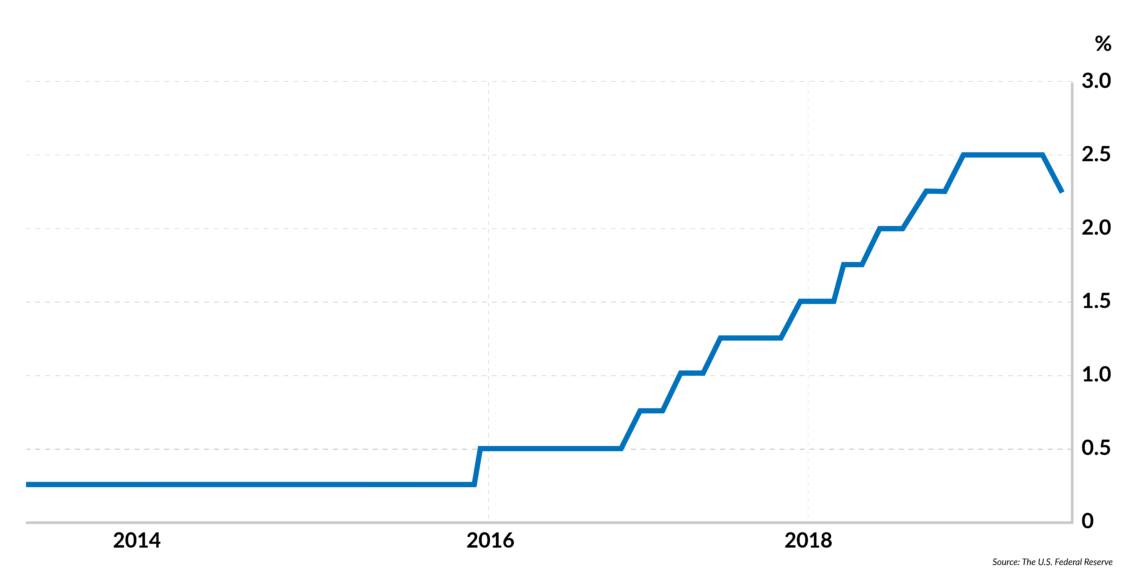

Federal Reserve Board Chairman Jerome Powell and President Donald Trump are the leading economic policymakers in the U.S. This summer, they both took the world by surprise. On July 31, the Fed reduced the funds rate target to 2.25 percent (the funds rate influences short-term interest rates, including those charged on credit cards). Doing so sent the message that the economy is not meeting expectations and a temporary boost in aggregate demand (and consumption, in particular) will take the economy back to its long-term path. Two important comments accompanied this move.

Facts & figures

United States federal funds target rate: upper limit

2014-2019

In accordance with the view that the long-term outlook for the economy is encouraging, Chairman Powell made clear that this reduction was not the beginning of a new period of loose monetary policy. However, he also blamed the Trump administration for having rocked the boat by engaging in a trade dispute with China that put world economic growth in jeopardy.

For his part, President Trump was hoping for a more substantial cut, and showed his disappointment at the Fed’s move, tweeting: “As usual, Powell let us down.” In the president’s view, the economy is a battlefield: retaliation against what is perceived as an aggressive move by the opponent is an essential part of the game and necessarily coincides with national interest. In this case, he expected Mr. Powell to cut interest rates significantly, because China and the eurozone had cut theirs.

Next, possibly intending to show his resolve, President Trump broke the commercial truce with China in early August and slapped a new round of tariffs on U.S. imports from that country (starting in September a new 15 percent tariff hit some $125 billion worth of imports from China). According to elementary economics, other things being equal, a drop in the demand for exports leads to a weakening of the exchange rate of the exporting country. Not surprisingly, the Chinese yuan weakened in the hours following Trump’s announcement. However, Mr. Trump jumped at the opportunity to create additional tension and painted the drop as hostile exchange-rate manipulation.

By and large, this is the legacy of the summer of 2019. Is this going to change the outlook for the rest of the year? There are two main scenarios worth considering.

Aiming for growth

One assumes the Fed believes that the key variable affecting growth is currently the trade standoff with China and that the central bank should enhance growth through loose monetary policy – as long as inflation remains under control (today, it is 1.6 percent). Under such circumstances, therefore, future moves depend on what the Fed and its chairman mean by satisfactory growth.

Since the annualized growth rate of U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) was 2.9 percent in 2018, 3.1 percent in the first quarter of 2019 and 2.1 percent in the second quarter of 2019 and since the Fed’s previous move was in December 2018 (it raised the funds rate target to 2.5 percent), one may guess that 3.1 percent is considered acceptable growth, but that 2.1 percent is not.

Growth depends on productivity, and it is not clear that lower interest rates raise productivity or encourage entrepreneurship.

Let us assume that satisfactory growth for the Fed is somewhere between 2.5 percent and 3.5 percent. Now, if the annualized growth rate in Q3 does not climb to 2.5 percent or more, and if President Trump does not find a quick way of easing the tensions with China, then we may expect the Fed to cut the funds rate to 2 percent before the end of the year. This will make nobody happy; it will be useless and perhaps even counterproductive.

Growth depends on productivity, and it is by no means obvious that lower interest rates raise productivity and encourage entrepreneurial talents. In fact, the opposite may be true.

Cheap loans often end up supporting questionable business ventures that under normal circumstances would be discarded outright. Furthermore, low interest rates discourage savings, which in turn are an essential element of sustained and healthy growth. And Wall Street will not celebrate, either. Stock markets have already benefited from low interest rates inducing investors to move their funds away from bonds to stocks. Lower interest rates are unlikely to bring more money to Wall Street because most of the money is already there.

Instead, the opposite might happen, as investors worry that their portfolios have become too unbalanced, and that something might go wrong as the economy sputters and public debt soars. It is telling that the interest rate on inflation-indexed 10-year bonds in the U.S. is 0.06 percent: investors have started looking for safe financial assets, regardless of the fact they offer zero returns in real terms.

The only exception to widespread discontent will be President Trump, who will be more than happy to blame the Fed for the disappointing economic performance (the president has promised a 3 percent growth rate through his term).

Priority: prestige

A second scenario could materialize if Mr. Trump transformed the simmering tensions with the Fed and the stalemate with China into a chance to boost his personal prestige and an excuse for having failed to honor his promises: the 3 percent growth, low taxation and balanced public accounts. Of course, in this case, concerns for one’s own image and prestige – this applies both to Mr. Powell and Mr. Trump – will prevail upon the concerns about the economy. What could happen then?

Maintaining President Trump’s image requires fresh ammunition, and he can hardly let Mr. Powell take the front seat.

Much depends on the president’s reelection strategy. He has two options. One is to intensify his warlike attitude and try to rally the country behind him, against America’s enemies – mainly China, but also the EU. He will then maintain that high public indebtedness and perhaps a “global recession” (a term that, according to Morgan Stanley, corresponds to worldwide growth of 2.5 percent or less) will be the price to pay to win the war under his firm presidential leadership.

On the other hand, Mr. Trump could try to strengthen his position by making a deal with China in early 2020, before the economic slowdown transforms an allegedly victorious agreement into what the American public could perceive as a botched, face-saving compromise.

We are moderately optimistic. Maintaining President Trump’s image requires fresh ammunition, and he can hardly let Mr. Powell take the front seat. Therefore, the resident of the White House will be looking for some kind of a coup de theatre to complete his first term and start another as “the Credible Leader who Tamed China.” A rapprochement with China would serve the purpose much better than a ferocious trade war that is losing support among Americans.

Beijing will ultimately decide whether to offer an opportunity for a reasonable settlement. We believe that it will. After all, the Chinese economy is in relatively bad shape. President Xi Jinping might think it is better to settle the trade dispute in the next six months rather than face President Trump fresh off a sweeping victory in November 2020.