Venezuela’s endless endgame

Bankrupt and in economic freefall, Venezuela has become the scene of a humanitarian crisis. The opposition is finally unified and appears close to being able to push the die-hard Chavista regime out. Much of the outside world, including Latin America, Europe, and the United States, is eager to help, but the devil, is in the detail.

In a nutshell

- In two years, the Venezuelan economy has shrunk by half and inflation has exploded to more than 2.5 million percent

- The Chavista regime that caused all this suffering may be on its last legs, with no income to run the country and few friends

- The endgame is complicated by outside actors, including Cuba and Russia, aiding the regime, and the U.S., threatening to use force

The pressure on Nicolas Maduro to resign as president of Venezuela grows more intense by the day. Since January, he must contend with a direct challenger who has laid claim to the office. As one member of the opposition put it, “The table is set for Maduro to resign.” A part of the problem, however, is that the table has been set as much by international actors, led by the United States, as by the internal opposition.

Curiously, the catastrophic living conditions in Venezuela are playing an asymmetrical role in the endgame: Mr. Maduro is oblivious to it, blaming the humanitarian disaster on the U.S., while the opposition, finally united after a year of internecine bickering, makes the promise to deal with the crisis a central part of its claim to legitimacy. Also, the economic calamity is a bridge to outside actors who might or might not intervene. Those external actors, in Latin America especially, are torn between their desire to defend democracy in Venezuela while easing the crisis there, and their intense opposition to the saber rattling by the administration of U.S. President Donald Trump.

Struggle to survive

Without belaboring the point, it is critical to understand just how bad the situation in Venezuela has become. For the past two years, its economy has been in free fall, losing almost 50 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP). Hyperinflation has reached staggering levels – 1 million percent for all 2018, according to the International Monetary Fund. In January 2019, the yearly consumer price index soared to 2.69 million percent. Daily life for citizens has turned into a constant struggle to survive. Venezuelan medical personnel estimate that at least one-third of all children under 10 years of age suffer from malnutrition whose effects will linger for the rest of their lives.

Venezuela’s dire straits are as much a function of corrupt management as of economic collapse.

The crime rate, at 80 murders per 100,000 people, is the highest in the world for countries not at war. At least 3 million Venezuelans have emigrated in the past two years, creating refugee problems in Colombia, Peru, Ecuador and Brazil. Shortages are so severe that the poor have trouble getting food to eat and the sick go without medicines or treatment. In short, today’s Venezuela represents the biggest humanitarian crisis Latin America has faced in decades.

Facts & figures

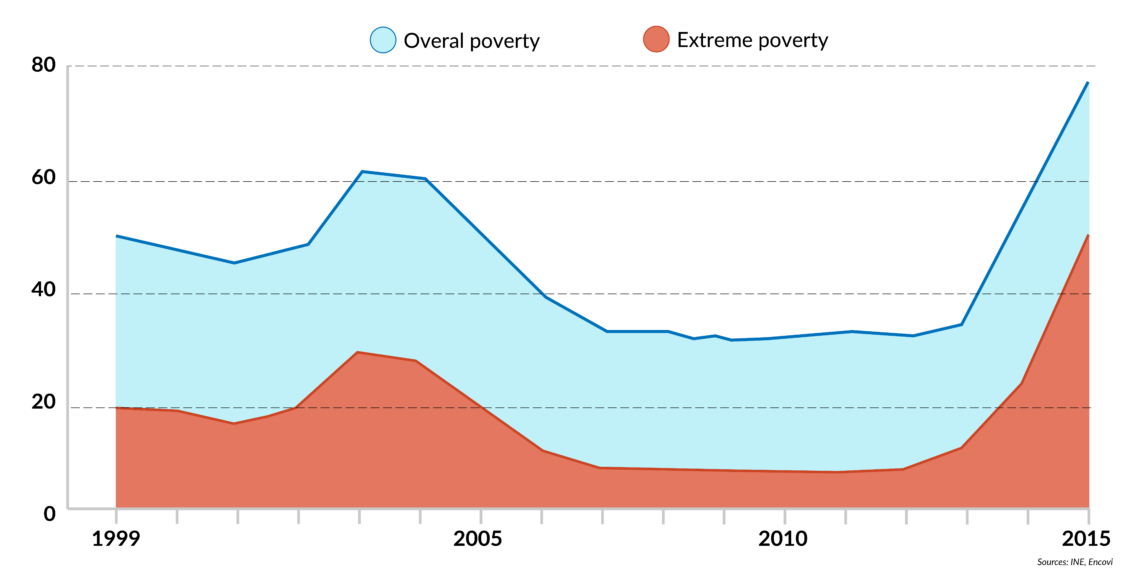

Poverty rates increased sharply under Maduro

Compounding these problems, the Maduro government is refusing all offers of aid – and there have been many, from European countries, the UN, and several Latin American states. The regime, though, denies that there is any crisis. In reality, Venezuela’s dire straits are as much a function of corrupt management as of economic collapse. Imports of food and medicine, for example, are supervised by military officers who enrich themselves by manipulating the government’s fanciful currency exchange rate policy.

Withering oil industry

Years of government mismanagement at the national petroleum company, PDVSA, have produced devastating results. The number of rigs pumping oil has declined for the past five years, bringing Venezuela’s oil industry to a cliff’s edge. In January 2019, only 27 rigs were working – down from a high of 120 in 1997. This attrition is the result of inadequate maintenance and investment.

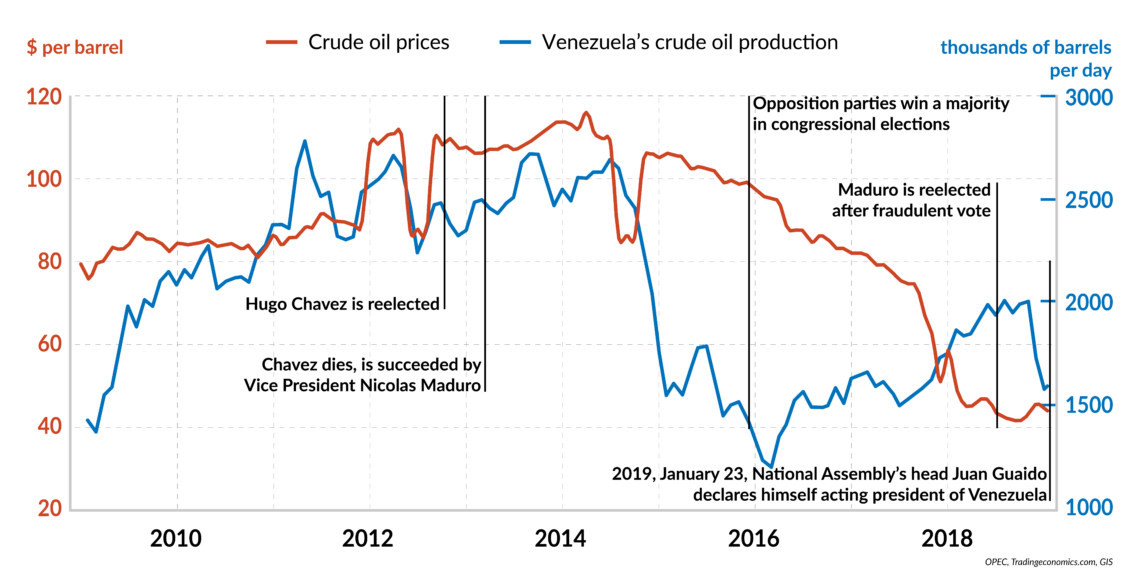

Oil production has dwindled over the past few years from more than 3 million barrels per day (bpd) to less than 1 million bpd. Moreover, this decline has coincided with a significant drop in oil prices since 2014. As a result, the Venezuelan government, which derives 90 percent of its revenue from oil exports, has been slowly starved into impotence.

Facts & figures

Venezuela's dwindling oil wealth under President Maduro

Interim president

Venezuela’s latest endgame (the regime has been on the ropes before) began on January 10, 2019, when Mr. Maduro had himself sworn in for another term as president after a brazenly stolen election. In doing that, he defied the verdict of at least 40 countries that had refused to recognize the legitimacy of the balloting. The pace of events accelerated on January 23, when the new president of the National Assembly, Juan Guaido, declared himself Venezuela’s interim president and demanded that Mr. Maduro resign. Since that day, the challenger has held almost daily rallies, calling on the military to abandon the Maduro regime and promising amnesty to senior officers who accept his offer.

The U.S. and dozens of other countries, mainly in Europe and Latin America, have recognized the self-appointed president as Venezuela’s legitimate ruler. The U.S., prodded by Republican Senator Marco Rubio of Florida, followed through by imposing a set of sanctions that make it very difficult for Venezuela to export oil to the U.S. or any other country that follows the American lead. The U.S. also has declared it would pass all revenues from Venezuelan oil over to the Guaido group, to be spent at its discretion.

While the sanctions seek to cut off the Maduro regime from its main source of funds, their immediate impact is to redirect the oil Venezuela exported to the U.S – about half of its current meager output – to other markets. Also, about 120,000 bpd of U.S. light crude shipped to Venezuela to be blended with its heavy Orinoco crude will now be stopped, making it harder still for Venezuela to export.

In the short term, China might be willing to increase its intake of Venezuelan oil, but that is not certain. The authorities in Beijing have been reluctant to pick another fight with the Trump administration by taking a high-profile position in support of the Maduro regime. Besides, shipping more oil to China would not help Mr. Maduro, as China takes the oil in payment for outstanding Venezuelan debt. It will not provide the regime with a desperately needed cash infusion.

External players

Beijing has other reasons to be cautious. China seems to have decided that the Maduro regime is beyond saving, and it does not want to alienate a successor government in Caracas. That could put at risk the $60 billion in Venezuela’s sovereign bonds that Chinese banks now hold. At some point soon, with or without a transition to a more democratic regime, Venezuela will have to renegotiate its external debt. China, which has the largest part of that debt, reportedly is prepared to bargain hard to keep its loss (“haircut”) on the bond holdings to a minimum.

Among the most formidable obstacles are the thousands of Cuban ‘advisors’ in Venezuela.

By contrast, Russia has spoken out vigorously in Mr. Maduro’s defense. Moscow is warning the U.S. not to step in, but without much cash to dispense itself and with a minimal regional presence, it has few cards to play – except for trying to block Washington through the United Nations where it has joined Iran, Nicaragua and Bolivia in condemning “U.S. intervention.” Aside from its holdings of Venezuelan debt (much smaller than China’s), Russia’s principal local asset is the 49 percent stake that its state-controlled oil company, Rosneft, holds in CITGO Petroleum Corporation (or CITGO). That U.S.-based refiner is majority-owned by Venezuela’s PDVSA.

Up to this point, neither President Trump nor Russian President Vladimir Putin has had anything to say publicly about CITGO. The company has been placing big ads in U.S. newspapers emphasizing that it is an American corporation working for Americans, a subtle distortion of the truth.

What is the next step in what most observers consider an inevitable transition in Venezuela? The governments of Uruguay and Mexico have offered to mediate between Mr. Maduro and the opposition. Pope Francis is ready to do the same. While mediation is clearly preferable to violence or a military invasion, it is by no means clear how it can be managed. The European Union has joined with Uruguay and Mexico to create an International Contact Group, tasked with monitoring the situation, but its capacity for action is not known. The Venezuelan opposition demands free, fair elections. The external actors want an end to repression and a return to democracy, as well as immediate relief for the humanitarian crisis. But there are big roadblocks, too.

Among the most formidable obstacles are the thousands of Cuban “advisors” in Venezuela who help run Mr. Maduro’s intelligence services and security forces. These formations have been used to contain street protests and have played a pivotal role in acts of violence against the opposition.

There is no evidence that the Cubans are getting ready to leave. Their presence, as well as Mr. Maduro’s personal ties with the political leadership in Havana, is what lies behind the “Cubanization” of the U.S.’s Venezuela policy. Senator Rubio wants to end the Chavista regime not only to help restore stability and democracy in Venezuela, but also to stop deliveries of cheap Venezuelan oil to Cuba. As a first step, he wants the Cubans out of Venezuela.

Follow the money

The Venezuelan military supports the regime and thus far has shown few signs of abandoning Mr. Maduro. Much of the military brass has prospered from being placed in charge of managing the nation’s food and energy supplies. Moreover, it is believed that a big part of the senior military cadre is involved with, or facilitates, the cocaine trade. Even if such officers were to consider Mr. Guaido’s offer of amnesty, they must be aware that the rewards they share under Mr. Maduro would shrink under his successors.

Another thorny question is what to do with those who have stolen huge sums from public coffers. Only a few months ago, a former national treasurer of Venezuela, Alejandro Andrade, was convicted in a Miami court of trying to launder over $1 billion on behalf of Mr. Maduro and his inner circle. How much more has been smuggled out? The regime sold some of the country’s gold reserves in 2018, supposedly for cash needed to run the country, but possibly also to stash money abroad for its functionaries’ retirement. A reported attempt to move 20 tons of the Venezuelan central bank’s gold into a Russian Boeing 777 that landed in Caracas in late January 2019 was canceled after the plan leaked to the international news media.

The opposition does not trust Mr. Maduro to honor any agreements that might result from mediation.

If not for the corruption and the ongoing violations of human rights in Venezuela, mediation would be relatively simple. The Maduro government – or some offshoot of it – would accept clean and fair elections after a relatively short interval, in exchange for the president and a few of his cronies being allowed to retire to Moscow or Havana. Even if both sides were willing to accept this solution, the road to elections would still be bumpy. The regime has corrupted voter registers, making it necessary to create new rolls under international supervision. Who will govern while this is done?

U.S. pressure

Meanwhile, the Trump administration is upping the ante. Private and public aid has poured into the Colombian city of Cucuta on the border with Venezuela. Mr. Maduro responded by ordering the road between the two countries blocked with large trucks and sent troops to seal the border. The presidents of Chile and Argentina have visited Cucuta to draw attention to the aid their governments are providing to the Venezuelan people. At his press conference on January 28, U.S. National Security Advisor John Bolton appeared to inadvertently disclose a confidential note that said, “5,000 troops to Colombia.” That fed more speculation about potential military action in Venezuela, even though Pentagon officials deny having received orders to prepare it. How the standoff at the Cucuta bridge unfolds could provide a good gauge of the likely speed of political transition in Venezuela.

The opposition does not trust Mr. Maduro to honor any agreements that might result from mediation. The Venezuelan strongman went through two rounds of mediation supervised by former Spanish Prime Minister Jose Luis Zapatero, but has failed to keep the promises he made then. At this writing, tons of aid are awaiting to enter Venezuela at the borders with Colombia, Brazil, and Curacao. Mr. Maduro, though, has ordered the borders closed. Only one truck with aid crossed into Venezuela from Brazil on February 23. At the same crossing point, Venezuelan forces killed two members of the local Pemon indigenous people who live along the border.

Mr. Guaido believes he will win this game. He has already published a Country Plan (Plan Pais in Spanish) that specifies the steps to be taken by a transitional government. Two prominent Venezuelan economists, now living in the U.S., have laid down comprehensive plans for the transition phase and economic recovery of the country. Mr. Guaido is ready to administer a transition focused on new elections. Can the International Contact Group act to facilitate a peaceful transition?

For Mr. Maduro, though, the pertinent question is different: Would he prefer to retire in Havana or sooner in Moscow?