Venezuela desperately needs humanitarian assistance

President Maduro of Venezuela is surreptitiously selling off oil assets. The EU is trying to set up negotiations. The U.S. is pushing for regime change. All of these attempts to solve the Venezuelan crisis fail to address a crucial factor: the suffering of the country’s people.

In a nutshell

- The Maduro government, the U.S. and the EU are all pursuing different methods for solving the Venezuela crisis

- None of these actors have a viable plan for how to alleviate the tremendous suffering of the country’s people

- If the international community does not deliver humanitarian aid soon, the crisis could turn into a catastrophe

For the past year, GIS has been asking how long the crisis in Venezuela can last. Since the beginning of 2020, there have been three significant moves aimed at solving the political confrontation that has nearly paralyzed the country.

First, the government of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro has quietly been privatizing parts of the petroleum industry. Second, United States President Donald Trump declared with much public fanfare that Juan Guaido was the legitimate president of Venezuela. President Trump promised that soon the U.S. would act to topple Mr. Maduro and install Mr. Guaido as the country’s ruler. Third, and with less fanfare, the European Union announced that it had decided to resume its efforts to achieve a negotiated settlement between Mr. Maduro and the opposition led by Mr. Guaido.

The problem is that these three actions target very different endgames.

Disparate goals

President Maduro has quietly reversed 50 years’ worth of policies nationalizing the country’s principal source of wealth because his government desperately needs the money to maintain its hold on power and to sustain the allegiance of the armed forces. However aggressively Mr. Maduro searches for foreign private investment in state-owned oil firm PDVSA, the fruits of his policy, according to GIS guest expert Dr. Francisco J. Monaldi, will not be available for several months.

President Trump’s policy is to oust Mr. Maduro and replace him with Mr. Guaido as the country’s leader. The EU, on the other hand, wants to bring the opposition and government together to negotiate what the bloc calls a transition to democracy. President Trump’s policy undermines efforts by the EU and the Lima Group of 12 Western Hemisphere states to broker a compromise between Mr. Maduro and the opposition.

President Trump’s policy is to thwart Mr. Maduro’s hold on power, without saying what will follow his ouster.

Washington’s new sanctions on Russian oil giant Rosneft, which holds 49.9 percent of the U.S.-based oil company Citgo, would appear to complicate matters. Citgo is majority-owned by PDVSA, which handed over the 49.9 percent stake in Citgo as collateral for loans from Rosneft.

However, according to Dr. Monaldi, “because of U.S. sanctions, no creditor of Citgo, PDVSA or Venezuela can seize Citgo or its shares without a special license. And in the case of [Rosneft], they would have to get authorized anyway by the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC).” Rosneft, however, is only one part of Russia’s strategic ploy in Venezuela. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov has pledged his country’s complete support for President Maduro on several occasions.

President Trump’s policy is intended to thwart Mr. Maduro’s effort to hold onto power, without saying anything about what will follow his ouster. But expelling Mr. Maduro from office will not, by itself, solve the nation’s problems.

Facts & figures

Alarming crisis

Meanwhile, the humanitarian crisis in Venezuela grows increasingly troubling. Sadly, none of the recent moves by the EU, the U.S. or President Maduro are intended to alleviate the suffering of the Venezuelan people in the coming year.

More than 4 million Venezuelans, over 10 percent of the total population, have fled the country. The electrical grid is in alarming disrepair – most of the interior suffers daily blackouts – but the government in Caracas is doing nothing to fix it. Health specialists from the United Nations estimate that more than half of the country’s children under the age of six suffer from malnutrition.

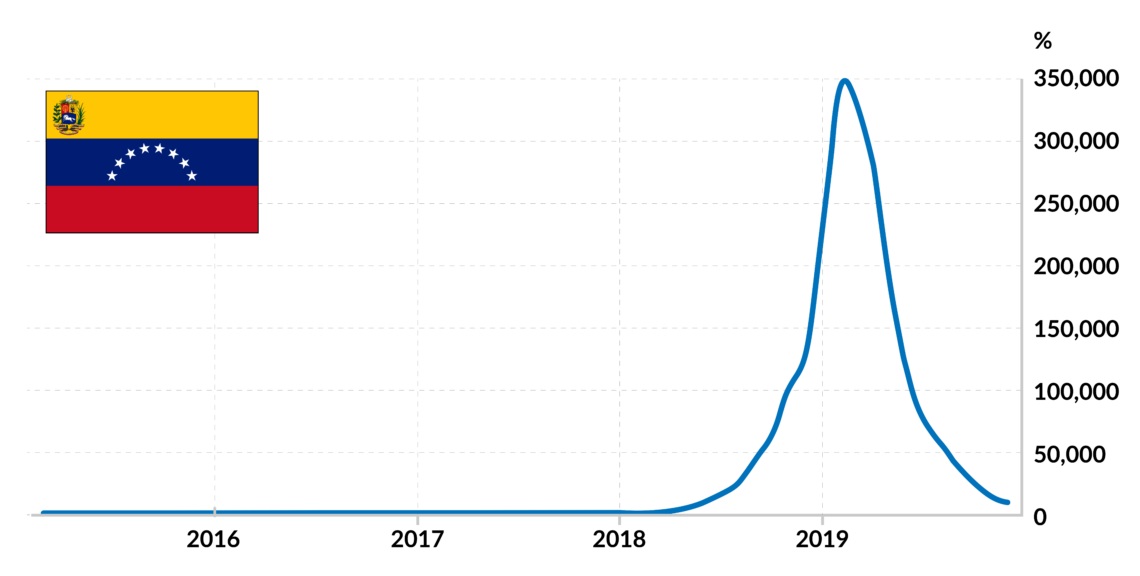

The death rate in Caracas, the capital, has soared – in part because of violence and in part because hospitals lack the personnel and equipment to deal with the sick. The economy continues to contract, having shrunk by more than a third in the past five years. Even before the coronavirus pandemic, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) predicted the Venezuelan economy would shrink by another 10 percent in 2020. The country’s international reserves have fallen by more than 50 percent in the past five years to $7.5 billion. Inflation runs rampant at thousands of percent per year.

The humanitarian crisis, together with the growing authoritarian bent of the Maduro regime, triggered massive, often violent upheavals in 2017 and again in 2019, when Mr. Guaido, as president of the National Assembly, first declared himself provisional president and the nation’s rightful leader.

Growing opposition

Public opinion polls make plain that opposition to the government continues to grow, even in the barrios, or poorest neighborhoods. The most vulnerable Venezuelans were once the staunchest supporters of the system and Mr. Maduro. Yet the political opposition that Mr. Guaido pretends to lead has fractured, divided by different strategies to achieve their goal and, in some cases, even different objectives.

The most radical among the opposition, many of whom live in Florida as part of the diaspora, want to encourage the Trump administration to invade and oust the ruling regime by force. Most Venezuelans reject that option but cannot agree whether to support efforts by the EU and the Lima Group to negotiate a transition. Another matter of deep disagreement is how severely to punish the government and its military allies once they have been removed from power.

The political opposition has done nothing to heal the wounds of inequality that have marked Venezuelan society for decades.

Volunteers and civil society groups in the barrios have found that, while many have lost faith in the government and with Chavismo – the social and political movement named after Mr. Maduro’s firebrand predecessor, Hugo Chavez (1999-2013) – that promised them so much over the past two decades, people survive by collective action. To deal with shortages and the lack of basics like water and electricity, groups have come together to form small communities in which people help one another.

What is striking in the reports of such work is the lack of linkage between these grassroots mini movements and the political parties that claim to represent the opposition. On the contrary, the political opposition has done nothing to heal the wounds of inequality that have marked Venezuelan society for decades.

The amount of available humanitarian aid is growing. However, the Maduro government is doing everything in its power to block it from entering the country, because enabling NGOs to carry out their work among the poor and vulnerable would strengthen the opposition to his government. Given that Mr. Guaido has access to Venezuelan dollar accounts in the U.S., this might be something he could do to ease the crisis and strengthen his opposition force.

President Maduro has eased some of the state’s control over foreign exchange and allowed partial dollarization of the economy. He appears to have negotiated some form of truce with the country’s largest private company, the food conglomerate Empresas Polar, which is now free to import goods and to bring in foreign exchange. However, these concessions eased the daily plight only of the relatively wealthy, those with access to dollars either overseas or under the proverbial mattress. It is easier now for a few Venezuelans to import goods that otherwise would not be available and enjoy the rejuvenated nightlife in the capital when the lights are on.

None of these measures have ameliorated the lot of the poorest, on whose behalf Mr. Maduro’s socialist government claims to govern. Inequality in Venezuela is greater now than it was five years ago, and the gap widens each day.

Clinging to power

Without external pressure, President Maduro can continue to cling to power, even without much help from PDVSA, as long as the military stands behind him. For the moment, armed intervention by the U.S. is unlikely, even in an election year with the votes of Florida at stake. With the departure of John Bolton from the National Security Council, no one close to President Trump is advocating that step.

The only effective intervention can come from the international community.

To complicate matters further, President Trump’s lawyer, Rudolph Giuliani, has taken on a wealthy businessman close to the Maduro regime as a client. The businessman faces criminal charges in a case in Florida where authorities say he was part of an effort to launder more than $1 billion. Mr. Giuliani is part of his defense team.

President Trump’s policy of sanctions is dulled further by the Treasury Department’s willingness to grant exemptions to those sanctions to U.S. oil companies so they can take advantage of the opportunities in the partial privatization of PDVSA.

The only effective intervention in Venezuela can come from the organized international community in support of holding verifiable parliamentary elections this year. That will not be easy. It would be easier if the Trump administration declared its support for such a peaceful course and focused its sanctions strategy on achieving that goal. Even if that were to happen, making sure the elections are free and fair will be a herculean task. A huge number of observers would be required to monitor such elections.

Coronavirus worsens the plight

Now, the COVID-19 pandemic has come into the picture. As of this writing, President Maduro has announced that there are 77 confirmed cases of the disease in Venezuela – this in a country whose health system already on the brink of collapse. Only a few major hospitals are still open and they were already short of critical supplies before the new threat.

The government has declared a quarantine and guaranteed all wages while suspending all payments of rent, loans and other such obligations. Given the existing poverty and informality of the economy for the poor, social distancing is impossible.

The extent of poverty and malnutrition in the country, combined with the fragility of the health system means some outside intervention will be necessary to forestall a national and regional crisis. The World Health Organization has announced it is ready to collaborate and the UN has called on all parties to suspend their hostilities to allow humanitarian aid to enter the country. Unless such measures are taken quickly, we will see a total collapse of the country in a very short time.

Against this backdrop, Mr. Guaido has made available to several hospitals and local NGOs some of the assets he controls in U.S. accounts. It is not clear how these groups can use the funds to acquire the necessary equipment on the international market. China has already delivered thousands of masks and test kits; Russia has delivered test kits and the Cubans have sent more than a hundred physicians. Still, the likelihood of a total collapse of the health system grows each day.

And it must be remembered that migrants escaping Venezuela – now well over 5 million and rising – will inevitably bring the disease with them as they cross the border into other countries. Whatever the endgame, something must be done this year to ameliorate the humanitarian crisis. If not, Venezuela’s population could collapse, as hunger, disease and deprivation escalate.