East-West conflict 2.0 brings a paradigm shift

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is the latest challenge to hopes that globalized trade will prevent wars. Instead, conflicts between democracies and autocracies are hardening.

In a nutshell

- Russia’s invasion threatens the rules-based international order

- The West is rediscovering the need for economic and military power

- China could play a major role in easing or exacerbating conflicts

On February 1, 1970, the first natural gas pipeline contract between West Germany and the Soviet Union was signed in Essen, after similar projects had previously failed due to an American pipe embargo. The Soviet Union undertook to supply 52 billion cubic meters of natural gas. In return, industrial giants Mannesmann and Thyssen supplied 2,000 kilometers of gas pipelines.

The barter deal was financed by a contract between Deutsche Bank and the Foreign Trade Bank of the Soviet Union. Starting in October 1973, the first gas flowed into the Ruhrgas AG network via Ukraine and Czechoslovakia.

Four more contracts followed this pattern until January 1978, with the result that East-West integration via pipelines in Europe became ever closer and the Soviet market share in German gas supply ever greater. The Committee on Eastern European Economic Relations celebrated the agreements as late as 2020 with an anniversary brochure.

Trade overrides American objections

Against American criticism, proponents of cooperation justified their stance with the argument, espoused by German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt and others, that “those who trade with each other do not shoot at each other.” The theory fits well with a new Eastern policy launched by a German social-liberal coalition, identified with Chancellor Willy Brandt, under the motto of “change through rapprochement.” Moreover, the replacement of the more toxic and expensive gas produced through coal gasification could be justified by its comparative cost advantages.

Whether the 1991 implosion of the Soviet Union and the dissolution of the Eastern Bloc can be attributed more to its imperial overstretch, which could no longer keep up the arms race, or to the softening from within because of the trade agreements with the West, is a matter of dispute to this day.

From the conservative side, the argument in the West was that trade with the East extended the life of the Soviet Union because its revenues fed the arms sector. Conversely, it was argued that the Soviet Union had proven to be a reliable supplier of gas, oil, coal, timber, grain and metal ores and had contributed to Europe’s security of supply in raw materials. This camp views geopolitics as an instrument for peace and prosperity.

Soviet acquiescence to reunification

A secondary aspect of domestic policy since the West German governments of Brandt (1969-1974) and Schmidt (1974-1982) was the establishment of a special relationship between the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and the Soviet leadership, which paid off in the Mikhail Gorbachev years and was continued by Gerhard Schroeder.

The United Kingdom and France were reserved about German reunification during the 2 + 4 negotiations, while the United States was more sympathetic. Ultimately, the agreement of the Soviet Union played a decisive role in making it happen. Moscow agreed on the condition that there would be monetary compensation for the withdrawal of its troops from the German Democratic Republic and that the Bundeswehr, Germany’s army, would not be stationed east of the Elbe River.

It remains disputed whether these talks included an agreement on the renunciation of the eastward expansion of NATO, as claimed today by the Russian side. Contemporary witnesses gave contradictory recollections.

Soviet collapse and peace dividend

The dissolution of the Soviet empire marked the end of the old bipolar world order. The U.S. became the only superpower, creating a “unipolar moment” in which Washington could establish a “New World Order.’’ The world happily collected a peace dividend of butter instead of guns, with rising social spending and declining defense spending. In the case of the Bundeswehr, the number of personnel was reduced from nearly 500,000 soldiers to about 180,000, from 10 to two divisions. The budget of the Ministry of Defense, long on a par with that of the Ministry of Social Affairs, fell to only one-third of the spending of the social ministry.

Russia was so weakened in the Boris Yeltsin era that it was unable to oppose the eastward expansion of NATO and the European Union. The Kalashnikovs and machine guns of the Red Army ended up on markets in Arab and African countries or in the hands of soldiers hired by private military companies. The U.S. even had to step in financially to prevent Soviet nuclear experts from leaving for Iran or other nations with ambitions of nuclear weapons.

9/11 and ‘War on Terror’

9/11 marked a new turning point. The “War on Terror” became the top priority. The U.S. military budget ramped up to take on the global responsibility of world policeman. Hybrid warfare tactics – including disinformation and cyberattacks – took the place of the classic interstate war. Countries such as Germany did not make much more than a symbolic contribution, with any change in the Bundeswehr slowed by lack of equipment and training.

The division of labor in this era went as follows: The U.S. took responsibility for the international “dirty work,” while middle powers such as Germany acted as free- or cheap-riders of U.S. hegemony and drew criticism by expanding the welfare state.

China’s rise and Putin’s takeover

Since China replaced the Soviet Union as the main challenge to Western alliances, pressure grew on NATO members to spend 2 percent of their economic output on the military. The Soviet Union tried but failed to challenge the U.S. militarily on a weak economic foundation. China took the opposite approach: once Beijing created a strong economic and technological foundation, it started catching up militarily.

Since Russian President Vladimir Putin took power in 2000, Moscow began restoring its ailing military sector, financed largely by the export of raw materials, just as during the Soviet days. Mr. Putin preferred to continue relying on this way of doing business, rather than committing to the restructuring of the economy. By then, oligarchs had taken the place of state-owned corporations.

The Russian leader does not have much time left to pursue his real goal.

The unrestructured economy is one reason why the Russian leader does not have much time left to pursue his real goal, the restoration of the Soviet or, better for him, the tsarist empire. Mr. Putin is almost a septuagenarian. There is the assumption that the Russian leader is suffering from a malignant tumor that is being treated with cortisone. Since this treatment causes water retention, this would explain his slightly swollen features.

Yet the end of fossil fuels, the economic basis of his imperial policy, is foreseeable in his lifetime.

Opposition was manifold to the Russia-to-Germany Nord Stream 2 pipeline, which would double the capacity of the existing Nord Stream 1 for a combined transport potential of 110 billion cubic meters of natural gas annually. Critics included the U. S., which wanted to sell liquefied natural gas to Europe. Eastern European countries feared losing their status as pipeline land-transit countries between Russia and Western Europe. Domestically, Germans opposed the second pipeline because it meant continued reliance on fossil energy at the expense of environmental goals.

Putin’s war on Ukraine

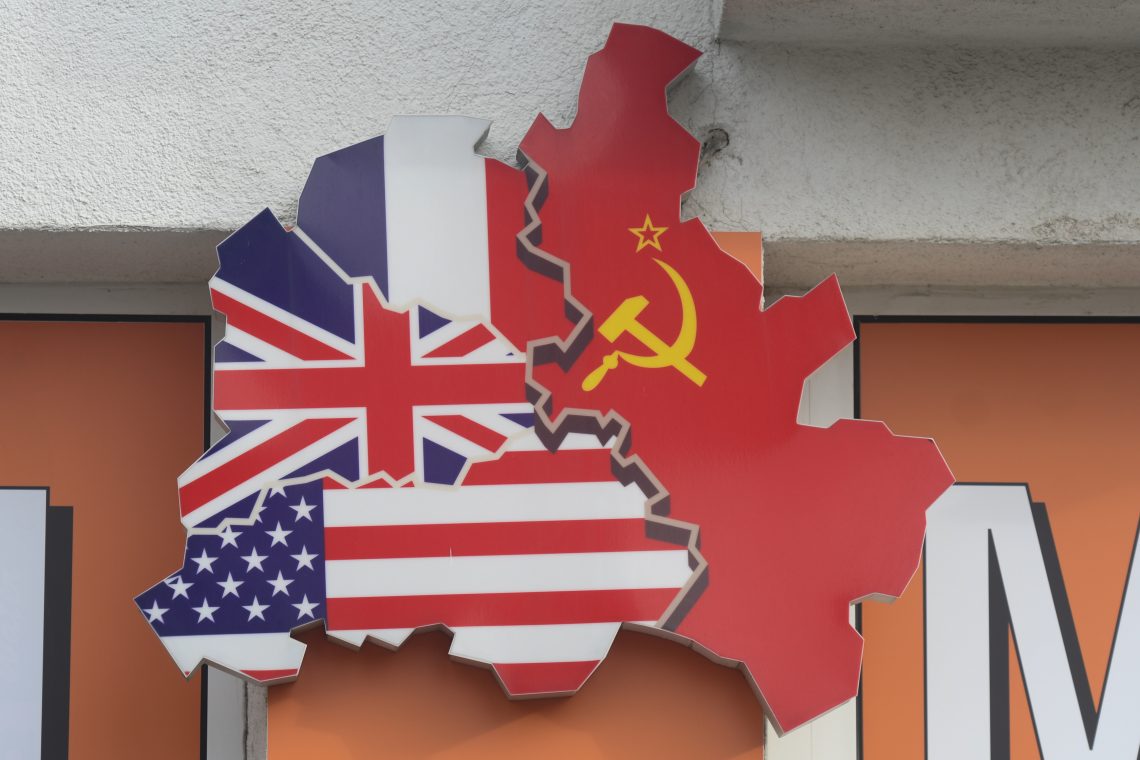

Early on February 24, 2022, another turning point for the world dawned with Mr. Putin’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The war rivaled the importance of the 1989 fall of the Berlin Wall and the 2001 attack on the twin towers of the World Trade Center. Russia’s attack came after a string of crises, from the 2009 global financial meltdown to the 2019 Covid-19 pandemic and many others in between – from refugees to climate change and rising populism.

Mr. Putin’s all-out war on Ukraine, which began in 2014, overturned the cherished peace order in Europe. After more than three months of the conflict in Ukraine, the consequences are not yet foreseeable.

Movements such as Fridays for Future, started in 2018 to spur action to stop global warming, may have pushed Mr. Putin to act more quickly in achieving his imperial ambitions while he was flush with oil and gas revenue.

How will America lead?

As the need for a stronger international order has increased, the U.S. willingness to lead it has waned, with the rise of populist ex-U.S. President Donald J. Trump’s “America First” mantra. U.S. President Joe Biden has sought to restore America’s standing abroad and reverse many of his predecessor’s policies. But he does so at a time when the U.S. has arguably lost its status as the sole global superpower. How it resolves its domestic political dilemmas will affect the world. Should the U.S. become more protectionist to counter China or continue to champion a free-trading international liberal order?

The new paradigm

The cascade of crises has triggered a paradigm shift in many respects. Idealistic cooperation of states relies on the premise that humankind is reasonable and capable of learning, particularly from lessons from history.

This notion has been shaken.

The rules of international law and norm-based action were supposed to reconcile differing interests using compromise, agreements and multinational organizations. But despots like Mr. Putin are neither reasonable nor rational. They live in a world of myths. Such dictators are why classic realist thinking has returned in the West, which again must rely on the logic of deterrence and, if this fails, on the logic of sanctions.

Conflicts cannot be eliminated, but they can be contained.

Conflicts cannot be eliminated, but they can be contained. For this logic to work, economic and military power is required – accompanied by the need to exercise it effectively when needed. The limits must be determined not by the ethics of conscience but also by the ethics of responsibility, which must consider the results of any action. President Biden can impose sanctions and even supply weapons but must not directly intervene militarily with U.S. forces because he would risk a third and possibly nuclear world war. Mr. Putin has threatened to use his vast military capabilities, including nuclear weapons, if he believes the survival of Russia is at stake. He can threaten openly because despots, unlike democrats, are less constrained by public opinion at home and are willing to suppress critics.

Europe is pulling together again, giving fresh oxygen to the expansion of the European Union and NATO, with previously neutral nations seeking to join. More Brexit-style votes are less likely in today’s climate.

Germany’s double shift

In Germany, there has even been a double paradigm shift.

The fulfillment of the 2 percent of GDP defense spending target is suddenly possible along with the structural reform of the Bundeswehr, leading to more troops and modern weapons. If realized, Germany as the largest economy in Europe, would also become the largest military power. Another change: even the ban on supplying armaments to conflict areas has been lifted.

Just as radical is the strategic rethinking of energy. It may lead to liquified natural gas replacing gas delivered through pipelines, as well as the possibility of extended lives for coal-fired and nuclear power plants.

Geopolitics is guided no longer by the expectation of peace, but rather by the preparation for emergencies so as not to be blackmailed.

Scenarios

Taken together, the world has entered East-West conflict 2.0, pitting the liberal world against the authoritarian one.

What has been brewing for years became evident in the vote of the United Nations General Assembly voted on March 2, 2022, to condemn the Kremlin’s war on Ukraine and demand the withdrawal of Russian troops. The Western press celebrated the 141-5 vote as proof that Russia is isolated. But 34 nations abstained, and 12 countries did not participate in the vote. This means that 51 nations, more than a quarter of the UN, did not condemn Mr. Putin’s war. If we consider the percentage of the world population that these countries represent, it was more than half because of the abstentions of China, India, Pakistan, Iran, Vietnam and others. Half of the African countries did not go along. Central Asian nations and Iran abstained or stayed away from the vote. Turkey voted in favor but does not take part in sanctions.

The cartographic image of the vote marks the New Silk Road. The contours of a China-directed bloc appear. Until China is militarily capable of replacing the U.S. as the international military power of order, the New Silk Road is supposed to function as an interim solution, providing no benefits to club members.

China has a lot at stake in this new world.

In the future, it will buy more Russian gas and oil and sell consumer goods and high technology, freeing Russia from its sanctions-induced isolation. But at present, bilateral trade with Russia is dwarfed by China’s stronger economic ties with the West.

China could stop President Putin but shows no signs of doing so. There is a strong argument to be made that an end to the war will be in the interests of both nations. China seeks to avert a world economic crisis while Mr. Putin seeks to preserve his regime-sustaining exports of energy and other raw materials.

Instead, the scenarios are so far playing out discouragingly. The world witnessed an arrangement between the two despots in the run-up to the Winter Olympics hosted by China. Mr. Putin held back his invasion until the Olympic Games ended. In return, he got Chinese President Xi Jinping’s implicit backing for the attack on Ukraine.

Without a change in the thinking of China and other authoritarian leaders, this means the East-West 2.0 conflict is in danger of hardening, not easing, for the foreseeable future.