Will Western Sahara trigger the next crisis?

Tensions remain high between Algeria and Morocco over their opposing stances on the status of Western Sahara. Fortunately, other priorities will likely constrain the conflict.

In a nutshell

- Morocco’s claim of sovereignty over Western Sahara is contested

- Algeria backs the Polisario Front’s fight for national independence

- Armed conflict remains unlikely due to other pressing interests

To understand Morocco’s recent evolution and trajectory, it is necessary to analyze its relations with other northern African countries of the Maghreb region.

Key among them is Algeria, its larger neighbor in population and size. The hostility between the two nations is long-standing and predominantly related to the desire for self-determination of the Polisario Front – supported by Algeria and opposed by Morocco, which considers Western Sahara, once a Spanish colony, as an integral part of its territory and regional influence.

Under the Madrid Accords of November 1975, Western Sahara was assigned two-thirds to Morocco and one-third to Mauritania, another Maghreb neighbor. The Polisario Front’s independence movement against Morocco was initially backed by Algeria and Libya. While Tripoli’s support to the Polisario ended with the 2011 death of Muammar Qaddafi, Algiers’ support remains alive and well.

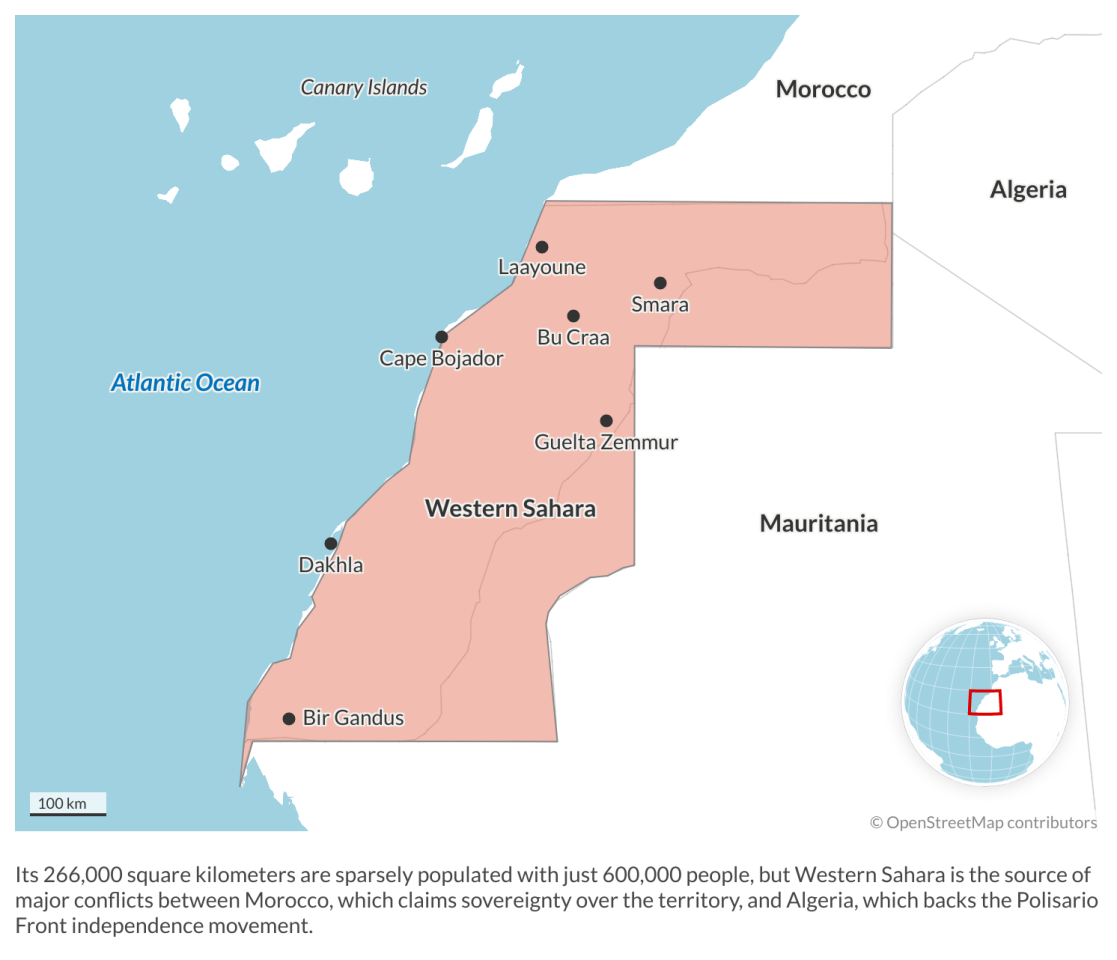

Since 1976, when the Polisario-dominated Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic was founded in the Algerian town of Tindouf, many things have changed, such as the relationship with Mauritania, which ceded its slice of land to the Polisario. That seemingly barren territory is not only a strategically important location, but is also rich in minerals like phosphates.

The road to detente

The United Nations Security Council is discussing the Moroccan proposal for limited autonomy in the Western Sahara region, despite a now-dormant 1991 plan to hold a referendum that would allow its citizens to vote on integration with Morocco or independence.

A cease-fire between Morocco and the Polisario Front lasted nearly three decades until hostilities resumed in 2020. Although not as violent as before, tensions remain high. In November 2020, then-United States President Donald Trump recognized Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara. The development damaged Morocco’s standing with the Polisario Front and its Algerian backers. Diplomatic relations between Rabat and Algiers broke off in 2021.

Also, in July 2022, Morocco recalled its ambassador to Tunis and did not attend an African investment conference after Tunisian President Kais Saied hosted Polisario Front leader and chairman Brahim Ghali. President Saied’s move underscored how difficult it is for Tunisia to abandon Algeria in favor of Morocco and why. Algeria supplies about two-thirds of the natural gas needed by Tunisia as well as significant volumes of electricity.

For its part, Polisario described a speech by Moroccan King Mohammed VI as full of lies and evil propaganda amid a recent Spanish U-turn in policy that delivered a blow to Western Sahara’s hopes for independence. Spain went from neutrality to support for Rabat’s 2007 proposal for limited self-rule of Western Sahara. As a consequence, Algeria suspended its friendship treaty signed in 2002 with Madrid and imposed trade restrictions, despite the energy crisis that Europe is experiencing, principally due to the Russian war on Ukraine.

The fight goes on over Western Sahara’s status

Controlling the flow of migrants

Tensions in western Africa have prompted Algiers not to renew the contract of the Maghreb-Europe gas pipeline, which supplied gas to Spain via Morocco. But if Algeria has influence through its gas and oil, Morocco has its own influence in the form of control of the migration flows. Indeed, it is no coincidence that Spanish Foreign Minister Jose Manuel Albares has repeatedly stressed the excellent relations between Rabat and Madrid: “At a time when all the irregular immigration routes used by the mafias which traffic in human beings are increasing in Europe, the only route that is not increasing but decreasing is precisely the one that, through the Strait of Gibraltar, reaches the coasts of Andalusia.”

Another source of regional tension is illegal migration. The two small cities of Ceuta and Melilla – with less than 80,000 residents each – are Spanish enclaves on the northern coast of Morocco, located 385 kilometers apart by land. Reinforced by anti-immigration walls built in the 1990s, they represent a European outpost on the African continent and physical proof of how difficult it is to contain migration flows. Over the years, the two cities have repeatedly been the target destination of thousands of people from both the sub-Saharan and the Maghreb areas.

Morocco has tried to curb this phenomenon – as evidenced by the pro-European immigration law of 2003 – but with little success, partly due to the lack of Algerian support.

Human rights and poverty

Although Morocco is one of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) countries that best withstood the instability of the Arab Spring, many problems remain: the regime in recent years has shown a hard fist against human rights activists, who were often condemned through sham trials. Complicating matters, in July 2021, news broke of the Moroccan government’s use of Israeli Pegasus software for the purpose of hacking into the data of some of its citizens who espoused anti-regime sentiment.

Looking at World Bank indices, nearly a quarter of the Moroccan population is poor or at risk of becoming poor, and the gap between the wealthiest and poorest classes is substantial: in fact, the inequality index has not changed since the beginning of the new millennium and poverty in Morocco remains among the highest in the entire Mediterranean. Some 15 percent of the population live below the poverty level and 12 percent of unemployment affects mainly young people between the ages of 15 and 24.

This, of course, is not good news for King Mohammed VI – who celebrated 23 years on the throne in July 2022 – and his government, which has resorted to force and arbitrary detentions to quell protests. In addition, the rights of women and minorities are still poorly respected, as highlighted by Human Rights Watch. Moreover, 90,000 refugees from Western Sahara remain in the Algerian refugee camps of Tindouf.

Facts & figures

Climate change concerns

Morocco is highly vulnerable to climate change. One stunning example is connected to drought. The water level of its dams has decreased from 49.5 percent in 2021 to 32.4 percent in June 2022, mainly due to a rainfall deficit of 64 percent. From September 2021 to January 2022, the average rainfall was about 38.8 millimeters. Normally, that figure would be about 106.8 millimeters. If drought in Morocco occurred once every five years prior to 1990, from 1990-2000 the trend increased to once every two years.

Heat waves are also on the rise. In a 56-year period (1961-2017), a widespread rise in temperatures was documented throughout the country, with a peak increase of 2.6 degrees Celsius registered in the central province of Taza, higher than the 2 degrees Celsius sought by UN climate goals.

Continued warming will harm agricultural production. Regarding water, the global effects of melting ice and rising sea levels could wreak havoc on Morocco’s vast 2,500-kilometer coastline, stretching from the Atlantic to the Mediterranean. The rising seas could harm the tourism that many coastal towns and villages rely on, besides causing damage to the ecosystem and agricultural production.

The government has not underestimated the emergency and has favored robust investments, as well as having already joined the Rio Summit since 1992, the 2002 Kyoto Protocol, the 2015 Paris Accords and 2016 COP 22.

In 2022, Morocco slipped from seventh to eighth place in the Climate Change Performance Index, still impressive compared to the U.S., which ranks 55. Mohammed VI has shown that he is very serious about the climate, investing heavily in renewable energy and seeking practical alternatives to agricultural woes.

Scenarios

There are two elements that are likely to particularly stress Moroccan society in the medium term: climate change and relations with Algeria over the status of Western Sahara, which are also likely to affect neighboring countries such as Tunisia and those closely linked to Rabat such as Spain. At least three scenarios are possible.

Tensions between Morocco and Algeria rise

This is the most likely scenario in the short term. Algiers’ harsh response to Madrid’s policy change looks to be more bark than bite. Algeria has other priorities looking beyond the Mediterranean, and these include its own repositioning on the global stage as a major energy exporter.

Algeria accepts Morocco’s stance

Thanks to the energy crisis caused by the Russian war, Algeria will focus more on its foreign relations, especially with European countries, assessing the rivalry with Morocco as unnecessary and ultimately counterproductive. This, unfortunately, is an unlikely scenario.

The crisis turns violent

This is a highly unlikely scenario, at least in the immediate term. Europe is keen on maintaining calm in a region already shaken by the Libyan civil war. Military conflict between Morocco and Algeria now would also harm energy agreements and benefit no one.