The Mekong region under the shadow of China

Because of rising tensions in “water diplomacy” around the Mekong River, the region could become another geopolitical hotspot along the South China Sea. The lack of external major-power involvement means China’s dominance is unlikely to abate.

In a nutshell

- China is gaining influence in the Mekong region through hydropower dams

- The dams cause unpredictable droughts and floods

- Unless ASEAN unites, China’s influence in the region will remain uncontested

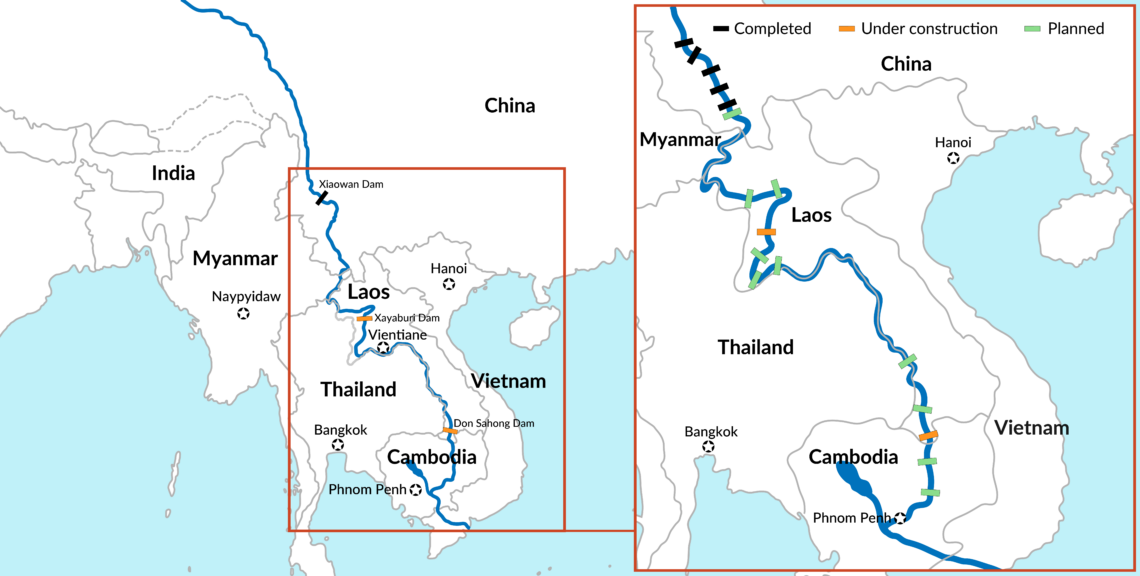

Over the past three decades, no region in Southeast Asia has attracted more attention than the South China Sea, where more than one-third of global shipping passes. However, the Mekong River in mainland Southeast Asia has now also emerged as a body of water of geopolitical importance. On the one hand, Beijing is manufacturing (and weaponizing) land in the South China Sea, and on the other, it is controlling water on land by building and operating a string of upstream hydropower dams on the Mekong.

The main difference between the South China Sea and the Mekong is that all major and middle powers near and far have put down stakes in the former, whereas the latter is mostly left to China and its smaller mainland Southeast Asian neighbors to sort out in an asymmetric fashion. The only major external power in the Mekong mix is Japan, which was the first donor and investor in the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) cooperation program in the early 1990s. Without the international attention granted to the South China Sea, the Mekong region – where the world’s 12th-longest river runs through a six-country region inhabited by 350 million people – has increasingly come under the shadows of Chinese dams.

Conceptualizing the mainland

The six countries that border the Mekong River – China and Myanmar upstream, midway through Laos and Thailand, downstream to Cambodia and Vietnam – are characterized by vibrant economic development, authoritarian upsurge and geopolitical dilemmas. Since 1992, Japan and the Asian Development Bank have promoted GMS cooperation for infrastructure development and capacity building.

Post-Cold War, the GMS comprised the five mainland Southeast Asian countries – Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, and Vietnam (or CLMTV) – along with China’s southwest province of Yunnan and southern Guangxi autonomous region. In the mid-1990s, the GMS became the geographic arena for several regional governance agreements and frameworks, namely the Mekong Agreement (MA), the Mekong River Commission (MRC), and the Mekong Institute (MI). Nearly three decades on, this space appears dramatically different.

The primary major-power rivalry in the Mekong space is between China and Japan.

Against the backdrop of broader infrastructure connectivity and economic cooperation within the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), China now towers over mainland Southeast Asia. While Japan tries to maintain its role, the United States has fallen behind in influence. As a result, the primary major-power rivalry in the Mekong space is between China and Japan, unlike the South China Sea where Beijing and Washington are locked in a face-off.

The Mekong mainland countries have emerged as a region of economic growth and development promise. However, they feature their own set of social and environmental risks, and they face domestic political contestation amidst geopolitical competition – a “great game” of sorts.

For example, Cambodia and Laos are firmly in China’s orbit, and both rely on Chinese aid, trade, tourism, investment, and loans. While enmeshed with Thailand on labor and migration, Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar are also under Chinese influence. Myanmar and Thailand have more latitude to strike a balance between China on the one hand and Japan and U.S./Western democracies on the other.

Facts & figures

The first-generation Mekong River cooperation system based on the MA, MRC, and MI is being eclipsed by new cooperative vehicles, namely China’s Lancang-Mekong Cooperation (LMC) in conjunction with the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the China Indo-China Peninsula Economic Corridor, and the Ayeyawady-Chao Phraya-Mekong Economic Cooperation Strategy (ACMECS).

A Thailand-led cooperative scheme with growing traction among the five Mekong mainland countries, the ACMECS counter-balances China’s LMC. Yet it is clear the Chinese cooperation agreement is now dictating the terms. China (and Myanmar) have always been MRC observers but not members. Without Beijing’s participation, the MRC and its sister agreements, the MA and MI, are limited in scale and scope. It has been less than five years since China launched the LMC with the countries along the river. Since then, two summits have been held and a series of operational plans and joint working groups have been launched, including think-tank dialogues and cooperation.

At stake is the string of upstream dams China has built. They have exacerbated volatile weather and water conditions, resulting in unpredictable droughts and floods attributable to Chinese behavior. These dams also have given China considerable leverage over downstream countries. For example, when drought conditions set in over Thailand and Cambodia before the annual monsoons set in, Chinese authorities have been known to release water from the Jinghong Dam at the request of the affected countries. This gives China political clout through a kind of “water diplomacy.”

The dams have exacerbated volatile weather and water conditions.

It has become obvious that China will play by its own rules through the LMC. This could also favor China in the contentious negotiations between ASEAN and Beijing over a code of conduct in the South China Sea.

Japan, having cultivated Mekong development since the early 1990s, is alarmed to see China assert its role in the region. Tokyo has stepped up its engagement by providing more aid and capacity building. However, unlike China, Japan lacks the next-door road and rail connectivity that comes with geographical proximity. Japan is also in no position to offer a regional governance scheme to match the LMC. Even with a multibillion Japan-Mekong cooperation framework through ventures such as connectivity and quality infrastructure, the most Japan and the Mekong mainland countries can bargain for is to synchronize and promote cooperation between the LMC and the MRC. However, China is likely to go along only if the MRC is subservient to the LMC.

These broader contours of the region are determined by the domestic political situations in each of the Mekong countries. The more shades of authoritarianism in mainland Southeast Asia, the more influence China is likely to wield. The authoritarian upticks in both Myanmar and Thailand play into China’s hand, as ruling regimes in these two countries seek Beijing’s support as a buffer against Western criticism. Laos is in China’s debt because of the Kunming-Vientiane railway, which is being built under Chinese auspices. Cambodia’s near-dictatorship under Prime Minister Hun Sen has been visibly answerable to China. Vietnam is the outlier, an authoritarian state at odds with China in both the South China Sea and the Mekong region. But as long as China remains Vietnam’s top trading partner, Hanoi is unlikely to stand up to a much bigger Beijing.

The baseline scenario in the Mekong region is China’s longer-term dominance.

Scenarios

Moving forward, the mainland and maritime halves of ASEAN will create a nexus of prosperity and insecurity. Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam will have to harness their development potential and manage wealth disparities within each country and across the broader ASEAN.

The Greater Mekong Subregion is a beckoning market of more than 350 million people, with a gross domestic product (GDP) half the size of ASEAN’s 2.5 trillion. But because of China’s new assertiveness and its unilateral water diplomacy, the CLMTV group has come into its own. The CLMTV countries have a combined GDP approaching 800 billion dollars and a market of some 250 million people. Minus Vietnam, the CLMT space alone offers a market of 150 million people and a GDP of half a trillion dollars, with Thailand as a natural hub. Most importantly, all of these regional development frames are expanding well into the foreseeable future. Even with Thailand’s laggard trend growth of 3 percent in the medium term, the overall growth trajectory of the Mekong mainland space is in the 5-6 percent range.

The baseline scenario in the Mekong region is China’s longer-term dominance. The U.S. is too far away and too preoccupied. Japan has limited punching power even if it is committed to the Mekong region for the long term as a donor and investor. Geography gives China the triple advantage of size, proximity and an upstream location.

It will be hard for other major powers to rival China in this space. However, a competing scenario could emerge if the CLMTV countries make the Mekong an ASEAN priority, as with the South China Sea. If the whole ASEAN rallies together behind downstream Mekong grievances, it would wield more bargaining power against China. Meanwhile, downstream countries will have to reconsider their own dam projects if they are going to challenge the presence of Chinese dams.

This scenario may be stretched further if the CLMTV countries manage to involve other great powers in the region. This would give the Mekong a status akin to that of the South China Sea, with China facing opposition from ASEAN members with other major powers in the mix. Naturally, Beijing would prevent and resist the regionalization and internationalization of the Mekong at all costs. But if the CLMTV decide to stand up to China, especially under Vietnam’s 2020 ASEAN chairmanship, then Beijing may well have a new geopolitical and geo-economic front to contend with.