Challenges and opportunities for Africa’s health systems

While some countries in sub-Saharan Africa improved their health systems, the region still lacks adequate healthcare on the whole. The situation is dire in countries with large populations in remote areas.

In a nutshell

- Rapid urbanization and sociodemographic changes are creating new health demands in sub-Saharan Africa

- Despite advances through financial and technological innovation, healthcare access and quality remain uneven

- Most countries risk falling short of the United Nations health goals for 2030

Health in sub-Saharan Africa faces a critical juncture. At a time of rapid sociodemographic changes and shifting disease patterns, the vulnerabilities of public health systems have become increasingly evident. Considering the limitations that characterize the health sector in most African countries – huge financing gaps, structural inefficiencies and lack of skilled personnel – even in the best of cases, only a limited number of countries are expected to reach the 2030 United Nations Sustainable Development Goal of ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being for all.

Multiple challenges

Disease patterns in many sub-Saharan countries are rapidly evolving amid widespread poverty and accelerating social change. Several countries are under the so-called double-disease burden, where health conditions often related to adverse economic, security and political conditions – malnutrition, low routine-immunization rates, infant and maternal mortality or cholera outbreaks – increasingly coexist with noncommunicable diseases such as cardiovascular illnesses, diabetes or mental health disorders.

These new conditions are often rooted in trends like substance and alcohol abuse, tobacco consumption and unhealthy diets. Rapid and unplanned urbanization in countries like Angola, Ethiopia, Niger, Nigeria and Tanzania is creating new health demands in environments marked by poverty, pollution and the lack of access to clean water and sanitation. However, the capacity of health systems to respond to these challenges and provide appropriate healthcare across age cohorts is severely compromised by inadequate funding, inaccessibility and persisting inefficiencies.

The health financing gap in Africa is estimated at $66 billion. While health has risen to the top of the political agenda in many countries, current indicators suggest that most states will not be able to close this gap. In 2014 (the latest data available), public health expenditure in the region was estimated at 2.3 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP) on average – well below the global average of 6 percent, in a region where the tax-to-GDP ratios are among the lowest in the world.

Good governance is necessary to improve health outcomes.

In addition, the 2017 median debt-to-GDP ratio was estimated at 53 percent, with about one-third of African countries classified as in debt distress or at risk of debt distress. Consequently, the share of out-of-pocket health payments as a proportion of health expenditure was estimated at 60 percent. Besides financial constraints, access to healthcare is particularly limited in conflict-torn areas and in countries with large but low-density populations.

Not surprisingly, health security levels in the region – the protection populations have from the effects of outbreaks and disasters – are low overall, as evidenced by the devastating effects of the Ebola epidemics in 2014, or the more recent cholera outbreaks in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and in Zimbabwe.

While partnering with the private sector is becoming part of the solution in many countries, the establishment of effective partnerships and the attraction of much-needed private investment is only possible under certain conditions, namely political stability paired with suitable health policies, adequate regulation and a sound business environment. Overall, good governance is necessary to improve health outcomes.

Facts & figures

Health in sub-Saharan Africa

- Sub-Saharan Africa remains the only region with a healthy life expectancy below 60 (52.3)

- Both under-five mortality and maternal mortality in sub-Saharan Africa have improved in the last two decades, but they remain the highest in the world

- According to data from the Global Health Observatory, while Africa accounts for more than 24% of the global burden of disease, it accounts for only 3% of health workers and less than 1% of financial resources

- According to data from the World Health Organization, a person living in Africa aged between 30 and 70 has a 20.7% chance of dying from chronic respiratory disease, cardiovascular disease, cancer or diabetes (a probability which is slightly above the global figure of 19.4%)

- A recent study has concluded that 29% of the population in sub-Saharan Africa lives more than two hours away from emergency hospital care. In South Sudan, for example, the figure is estimated at more than 77%

- According to the World Bank, the share of out-of-pocket health payments as a portion of all health expenditures in sub-Saharan Africa rose from 40% in 2000 to over 60% in 2014, ranging from 5% in Botswana to 72% in Nigeria

- African countries have the smallest percentage of public employees with health insurance or social security (estimated at 54.1%), and among private employees the figure is significantly lower, estimated at 27.8%

- In most countries, development aid remains a crucial provider of health funding: according to the OECD Development Assistance Committee, 21.2% of the development aid to Africa was channeled to the health sector

- Around two-thirds of the current PPPs in the region are located in East and West Africa. Central Africa, with the poorest health outcomes, has less than 10% of the PPPs.

- Africa manufactures less than 2% of the medication it consumes. Imports account for over 70% of the pharmaceutical market in Africa, which is worth about $14.5 billion

Universal coverage

Universal health coverage (UHC) for 80 percent of expenses or more remains a pipe dream for many countries. However, recent years have been marked by unprecedented progress. A critical step in this direction has been the implementation of social health insurance mechanisms in countries like Gabon, Ghana, Kenya, Mali, Nigeria, Rwanda, Tanzania and Togo. In many countries, the path to UHC is paved by collaboration between the public and the private sector. Countries opt for mixed financing solutions, combining salary deductions, mandatory contributions in the informal sector, private investments and aid flows. The road ahead is long, as both the accessibility and quality of health insurance in the region remains extremely low.

Expanding access to healthcare is necessary for improving health conditions across sub-Saharan Africa, as it remains far from sufficient. Nevertheless, with the current challenges ahead, improving quality is equally urgent.

Partnering with private investors and designing innovative financing mechanisms will be crucial to expanding access to healthcare, especially in a region characterized by debt distress, high unemployment rates and large informal sectors. It is important to note, however, that the private sector already represents 60 percent of the value chain for health, including medical provisions, manufacturing, distribution or retail. Almost one-third of health expenditure in Africa comes from private sources, including both out-of-pocket spending and private or voluntary health insurance programs. The scope for improvement remains enormous: public-private partnerships (PPPs) are limited to a small number of countries (with 10 out of 54 countries accounting for half of those partnerships, according to the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa).

This development stage also presents a window of opportunity. While African governments are increasingly willing to establish health PPPs in order to expand both the accessibility and the efficiency of their health systems, the healthcare and wellness sectors in Africa – estimated to be worth $259 billion in 2030 – are attracting large-scale investors.

Facts & figures

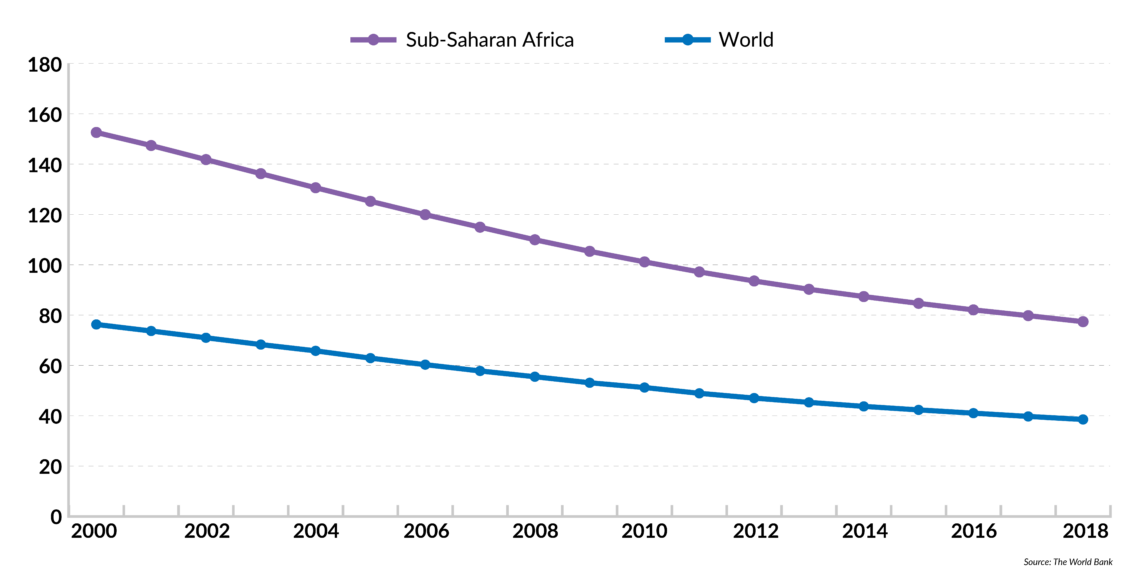

Under-five mortality rate in sub-Saharan Africa

(per 1000 live births)

Finding adequate funding will be crucial for countries to overcome health challenges and cope with issues like geographic constraints and the double-disease burden. Mobile devices and digital platforms are proving instrumental in improving the situation. In Kenya, for example, Safaricom, CarePay and PharmAccess have come together to create the M-TIBA, a mobile health wallet that allows people to save, send and spend money on healthcare.

In Uganda, people have access to a free SMS service – U-Report – where they can receive health-related information. In Ghana, a tech company has created a method to address the problem of counterfeit drugs through a mobile service that confirms the authenticity of medicines bought in pharmacies. Telemedicine is also playing a critical role as a complement to healthcare services, particularly in remote areas.

When looking at the performance of health systems across sub-Saharan Africa, four factors seem to determine positive outcomes: income, developmental status, demography and geography. In 2016, the four top performers were Cape Verde, Mauritius, Seychelles and Rwanda. These four countries are also top economic performers; three of them are islands, while all four of them combine small populations with high population density. Mauritius, Seychelles and Cape Verde are also the top three performers in governance and leadership according to the Ibrahim Index of African Governance, while Rwanda occupies the eighth position in the ranking.

This development stage also presents a window of opportunity.

In countries like Botswana, Kenya, Ghana and Ethiopia, governments have made major efforts to improve healthcare indicators. In Ethiopia, decentralization – achieved by scaling up community health programs – has been critical for the reduction of child and maternal mortality. In Ghana, significant progress towards UHC has been made thanks to the creation of community-based health planning services (CHPS) that deliver primary healthcare.

In the Rwandan case, often cited as Africa’s success story, the creation of community health insurance (Mutuelles de Sante) combined with a performance-based system has opened the door for near-universal penetration of primary healthcare (92 percent) and significant efficiency gains. National health policies combine private sector involvement and cutting-edge technology. This success, however, it is not easily replicable as it also involves large amounts of external aid (about half of the country’s health budget is funded by donors) and strong leadership.

In Kenya, President Uhuru Kenyatta is pursuing an innovative policy based on close collaboration with the private sector. The public healthcare sector is poor, the penetration of health insurance coverage is estimated at only 19 percent (with only 3 percent through private insurers) and around 1 million citizens are driven below the poverty line by healthcare-related expenditures every year. The main component of the government’s health strategy is a financing model – Managed Equipment Services (MES) – based on PPPs. The MES provides public hospitals with access to health infrastructure, modern technology and/or services from private sector providers through flexible and long-term contractual arrangements. In Botswana, PPPs have played a crucial role in decreasing the incidence of HIV and tuberculosis.

Scenarios

The future of healthcare in sub-Saharan Africa will largely be determined by events in the countries that are presently at a crossroads. Nations with high populations where rapid (and often unplanned) urbanization coexists with persistent feelings of regional marginalization and high levels of rural poverty face the double-disease burden. This is the case in Angola, Kenya, Nigeria, Tanzania and Ethiopia. Considering this, two scenarios emerge.

Base scenario: Falling short of expectations

Under this first, more likely scenario, most sub-Saharan African countries will fail to attain the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal of ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being for all by 2030, despite the current momentum. The performance of health sectors will remain uneven, creating further inequalities among countries and regions. Overall progress – both in accessibility and quality of healthcare – will be largely insufficient in the face of current challenges, but some countries could still make considerable headway.

In countries like Kenya, Ghana, Senegal, Namibia and Botswana, progress will be achieved through a combination of political stability, good health policies, adequate funding and leapfrogging unnecessary development stages. However, health progress could stall – and possibly deteriorate – in critical countries like Angola, Nigeria and South Africa.

Under this most likely scenario, failure will be determined by adverse policies, political and social instability and excessive reliance on foreign funding, at a time when development aid per capita is declining.

These factors, either alone or combined, will prevent governments from addressing critical challenges in due time. In South Africa, for example, the introduction of a national (and universal) health insurance program – estimated to cost 256 billion rand a year – at a moment of economic decline, high unemployment and social unrest is unlikely to prove successful. In Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country, the government will struggle to fund the health gap as the country becomes ineligible for a series of external health financing funds.

In Angola, despite the growth cycle of the 2000-2010 period, the health system could remain extremely inefficient due to drug shortages and lack of trained personnel. According to the 2019 “Healthcare and Economic Growth in Africa” report, Angola’s health system – along with those of Chad, Mauritania, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, South Sudan and Zimbabwe – are under severe stress.

Considering that access to healthcare and education are critical determinants of productivity, this scenario would have long-lasting consequences for growth and development in sub-Saharan Africa. An important number of countries will not reap the benefits of the so-called demographic dividend.

A large-scale epidemic could have disastrous consequences, given the low levels of prevention, surveillance and reaction mechanisms in several African countries.

Scenario 2: Overall progress

Under this much less likely scenario, the next decades will be characterized by significant change for the better. Although health systems in conflict-torn countries will stagnate, or even deteriorate, sub-Saharan Africa will score health achievements through innovation in financing and technology. While development aid flows will remain volatile, investment could increase significantly, reaching both moderate- and high-risk countries. This scenario would depend on accelerated innovation on two critical fronts: funding and operationalization.

Some countries could implement successful and cost-efficient UHC programs by solving some of their most pressing challenges, including the disproportionate size of the informal sector. In this case, a virtuous cycle would begin, in which overall improvements in health conditions would lead to longer, more productive lives and higher earnings, thus accelerating demographic transition processes.