AUKUS in perspective

The formation of the AUKUS security pact between Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States was greeted with mixed reactions in Europe and Asia. But despite a rocky start, the alliance has the potential to become a powerful security actor in the Indo-Pacific region.

In a nutshell

- Previous frameworks could not contain China

- AUKUS marginalizes Europe as a security actor

- The alliance has put Beijing on the back foot

- South China Sea issues could challenge the pact

At a press conference on September 15, 2021, Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison declared: “Friends, AUKUS is born.” Speaking jointly with United States President Joe Biden and United Kingdom Prime Minister Boris Johnson, he announced the formation of a trilateral security pact between nations that “have always seen the world through a similar lens.”

A media flurry ensued, fueled in part by extensive coverage of the resulting diplomatic spat between France and the three countries. The AUKUS launch came with an announcement that Australia would be provided with nuclear-powered submarines – de facto invalidating an earlier deal with Paris and prompting French Foreign Affairs Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian to speak of a “stab in the back.”

The French government’s ire initially received the most media attention, overshadowing longer-term geopolitical ramifications. But AUKUS goes far beyond commissioning submarines for Australia. The three heads of state have outlined a series of ambitious goals for the new framework, with the overarching aim of improving “joint capabilities and interoperability.” The pact, they declared, will “focus on cyber capabilities, artificial intelligence, quantum technologies, and additional undersea capabilities.”

Beyond these general aims – which overlap with those of existing security frameworks to which the three countries belong, like the Five Eyes group – the alliance has a more specific purpose: to “help sustain peace and stability in the Indo-Pacific region.” While no mention of China was made, it is broadly understood that the pact is a response to mounting Chinese adventurism in the region. AUKUS shows that Australia, the UK and the U.S. are committed to keeping Beijing in check, although each country will face different challenges in doing so.

Australia stands its ground

For Australia, AUKUS is the tangible peak of a trend long in the making. A cultural outsider in the Indo-Pacific region, the country has had to calibrate its foreign policy carefully to best serve its interests. For the greater part of the last decades, Canberra sought balance between geographic necessity and cultural affinity by seeking closer ties to the rapidly growing Asian economies in its immediate neighborhood while still cooperating with the U.S.-led West.

This strategy was thrown off course by the rise of an aggressive contender for not only regional, but also global, dominance. More than any other country perhaps, Australia has found itself caught in the crosshairs of China’s newfound confidence on the world stage, prompting a realignment in Canberra.

In early 2021, GIS expert Urs Schoettli writes that “China is betting on its ‘wolf warrior’ diplomacy to intimidate Australia. However, for the time being, the government stands firm, and Australian business leaders, who earlier on had advocated a cautious approach, are now supporting a tough line.”

Australia has stood its ground despite the multifaceted tensions that developed in recent years. After a trade conflict and several diplomatic and security disagreements, Canberra is sending China a clear message with AUKUS.

While Australia’s decision to join the pact is aligned with earlier responses to China’s expansionism in the Indo-Pacific, it is arguably one step further than the country has ever gone before. The country’s membership in the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) was not nearly as significant, argues GIS expert Dr. Thitinan Pongsudhirak:

The Quad did not fulfill its purpose because the combined heft of India and Japan has been insufficient to take China to task. … [N]o country with a direct land or maritime border with China is willing to openly incur Beijing’s wrath. This is why the Quad can only go so far. AUKUS goes further partly because it comprises only countries with no direct borders with China.

AUKUS’ role as a deterrent in Australian-Chinese relations will become more obvious in months to come, but it will undoubtedly allow Canberra to draw red lines. Dr. Pongsudhirak further argues that for Australia, the security pact heralds a future as “a strong, solid middle power that will stand tall in pursuit of its national interest.”

Another element that will influence AUKUS’s significance for Canberra is whether New Zealand joins the alliance, although in the early stages this appears unlikely. The head of the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, Admiral John Aquilino, has stated that “[w]e haven’t discussed specifically adding to AUKUS with other nations at this point.” Furthermore, New Zealand, like many European countries, is on a markedly different path of conflict avoidance. GIS Founder and Chairman Prince Michael of Liechtenstein warns that pursuing this strategy could “lead to the worst outcomes on both fronts – compromised values and losing the Chinese market.”

The UK as a global actor

If, for Australia, AUKUS is a declaration of strength, for London it is a declaration of independence. Having now left the EU club, the UK has gained total freedom to chart its own path when it comes to defense. The new pact shows the country hopes to regain some of its great-power clout. GIS expert Alexander Neill writes that the alliance “will provide substance for UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s ‘tilt’ toward the Indo-Pacific and potential military exports to the region, underpinning his ‘global Britain’ mantra.”

The new framework is also a shift away from Europe. It marginalized France, one of the most active and ambitious European security players in the Indo-Pacific. The pact, writes Prince Michael of Liechtenstein, “robbed [the French] of their illusion that post-Trump America would consider France a primary ally.”

For the European Union, writes Dr. Pongsudhirak, AUKUS is an “existential challenge:”

By further undermining the European project, AUKUS has intensified Brexit’s impact. The maintenance of the rules-based international order, a primary objective of the EU’s Indo-Pacific strategy, will be harder to achieve because the AUKUS pact is aimed directly at containing China.

Meanwhile, AUKUS demonstrates that the “special relationship” between the U.S. and the UK has stood the test of time and may prove the bedrock of the Western response to Chinese expansionism. GIS expert Dr. James Jay Carafano believes the pact reflects the UK’s willingness to collaborate with the U.S. on defense issues, despite some points of contention between President Biden’s Democratic administration and Prime Minister Johnson’s Conservative cabinet. While the UK may “demonstrate much more willingness to buck the Biden administration on issues where London disagrees,” he writes, it will also “continue to lean forward” on cooperation in the Indo-Pacific.

The U.S. seeks allies

After the Trump years, marked by open economic confrontation with China on one hand and rolling back overseas presence on the other, the Biden administration has opted for a slightly recalibrated foreign policy. Dr. Carafano further writes that “[t]here are elements of continuity and chaos in the developing defense policies of United States President Joe Biden. … Nevertheless, hard power has not diminished as a core instrument of American security policy.”

Despite the much-publicized shortcomings of the Afghanistan withdrawal, Washington appears committed to maintaining its security footprint abroad, with a particular focus on the Indo-Pacific region. President Biden has adopted a mellower tone than former President Donald Trump, even going as far as to “set a nonconfrontational foundation” for dealings with China, writes GIS expert Dr. Junhua Zhang. But this new approach notwithstanding, Washington and Beijing are still locked into a rapidly evolving systemic rivalry. From the American perspective, AUKUS should be seen as a new, better-defined framework for intervention should China overstep its boundaries. It is also undoubtedly a response to the expanding Chinese nuclear program, which has “quelled [domestic] demands to defund the nuclear triad, scrap missile defense or end nuclear modernization.”

But the alliance also signifies that, while the U.S. is willing to defend the current world order, it would rather not do so on its own. By leaning on trusted allies, Washington may hope to share the burden of having to tackle China as a contender for world dominance, and more such joint security pacts could be on the agenda for the U.S. “There are already signs,” writes Dr. Carafano, “that the U.S. needs to undertake more initiatives like the recent [AUKUS] agreement to work on nuclear submarine development.”

Facts & figures

China reacts

While President Biden and President Xi have veered toward appeasement on the diplomatic front, in practice both countries are gearing up for confrontation. China has spectacularly expanded its military capacity in recent years, systematically “working on new ways to defeat U.S. defense systems.” Mr. Neill further explains that:

China has been working hard on developing a nuclear triad. In addition to … land-based assets, it will incorporate submarine-launched and air-launched nuclear weapons. China may have created its military outposts in the Spratly Islands in the South China Sea to protect its new sea-based nuclear deterrent, while its new range of strategic bombers is designed to offer China ‘assured retaliation,’ if the U.S. were to mount a nuclear attack.

GIS experts argue that an alliance like AUKUS would have inevitably come along. Nevertheless, Chinese officials reacted to the pact announcement with outrage and thinly veiled threats. In their eyes, Dr. Pongsudhirak writes, the blame probably lies with Australia, “first for picking a fight by accusing China of starting the pandemic and then, after a trade and tariff war as retaliation, for getting its bigger friend and cousin to gang up on Beijing.”

Chinese leadership also responded by accusing the three AUKUS countries of dragging the region into a nuclear arms race. “Chinese diplomats are … deliberately conflating nuclear propulsion with nuclear armament,” argues Mr. Neill. “Commentators from the strategic community in China insist that Australia joining AUKUS is tantamount to it becoming nuclear-armed.”

Behind Beijing’s saber-rattling may lie genuine fears that AUKUS will shift the Indo-Pacific power balance in favor of the West. The alliance brings together nations with long naval traditions, which China lacks. But whether the tension stirred up by the pact will escalate or die down will be dictated by broader geopolitical issues.

Divided region

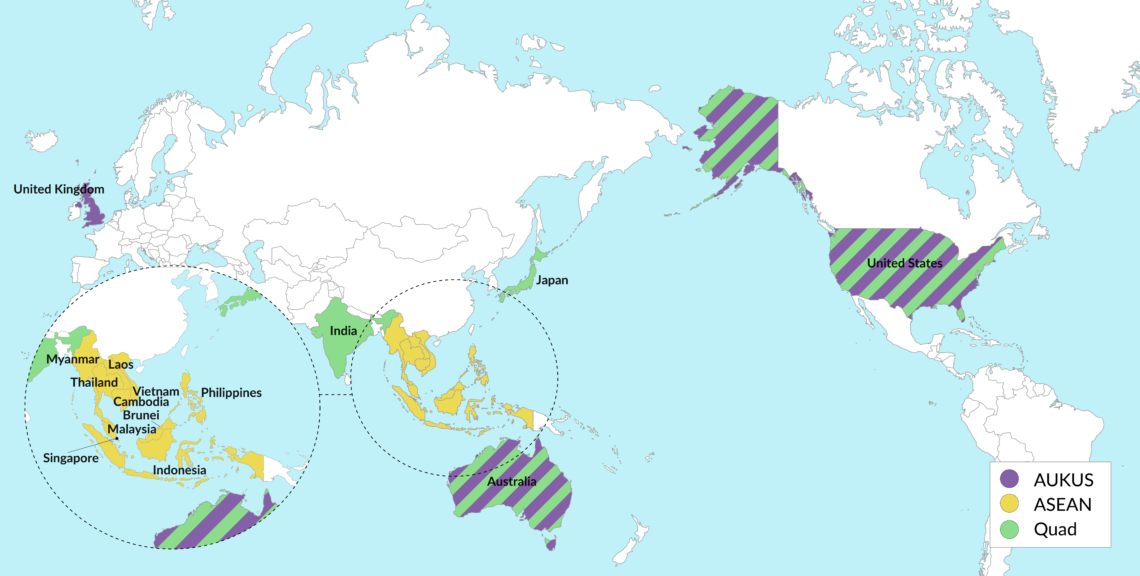

While the creation of AUKUS has, by and large, been positively received by Western analysts, in Asia the pact has proven divisive. The alliance will likely eclipse the Quad, and it may also end up pushing ASEAN aside as a security actor in the region because of mixed reactions among member countries.

Dr. Pongsudhirak argues that “China has divided ASEAN on South China Sea issues and brought Cambodia and Laos into its fold.” Now, he believes “AUKUS will further polarize the group, already hobbled by Myanmar’s postcoup crisis. Malaysia and Indonesia, as opposed to Singapore and Vietnam, are not in favor of AUKUS. The trilateral deal may complicate related cooperative vehicles.”

Meanwhile, Japan and South Korea came forth with carefully worded statements, hinting at concerns that the alliance would pressure them into adopting a more aggressive stance toward China. In answer to Prime Minister Johnson’s assurances that “AUKUS will not cause any regional problems,” South Korean President Moon Jae-in merely responded that he hopes “AUKUS will contribute to regional peace and prosperity.” In a similar vein, Japan’s foreign minister said the country “welcomes the launch of AUKUS in the sense of strengthening engagement in the Indo-Pacific.” Taiwanese reactions were marginally warmer, although also prudent.

Since AUKUS is meant to protect the status quo order while China wishes to challenge it, further developments will be contingent on how far the Communist Party decides to take its push for hegemony. The threat of invasion still hangs over Taiwan. AUKUS could prove deterrent enough to prevent China from moving in. If not, the pact’s defining moment could well be how it responds to an outright conflict in the South China Sea.