Brexit’s impact on UK energy policies

Brexit will have a profound impact on the energy sector of both the UK and the EU. Britain’s energy system will remain deeply tied to the rest of Europe’s, but questions surround how differences in regulatory environments will be bridged.

In a nutshell

- The UK’s energy sector is deeply entwined with continental Europe’s

- Brexit will add to the tough challenges it already faces

- The UK will lose influence over the rules governing Europe’s energy market

Time is running out on the Brexit negotiations between the United Kingdom and Brussels, with Britain’s exit from the European Union set for March 2019. The conditions the sides negotiate will have huge significance for their energy security and climate policies. Regardless of whether Brexit is “hard” or “soft,” the UK will remain reliant on its gas and electricity interconnectors with the EU, as well as on regulations underpinning the Internal Energy Market (IEM).

The dilemma for the UK is not just whether it remains in the IEM, but also its lack of influence over that market’s rules, despite its gas and electricity interconnectors with continental Europe. These problems will further complicate the many challenges the UK faces as it works toward transforming its energy system and its climate policies.

The British energy transformation strategy envisages phasing out the country’s coal consumption (despite the renewal of the country’s carbon capture and storage program), boosting renewable energy sources and (shale) gas production, as well as modernizing and building new nuclear power stations. However, constructing new nuclear power plants and exploring for shale gas based on fracking technologies both face frequent criticism as being too costly or environmentally dangerous.

It is unlikely the EU will allow the British to cherry-pick the rules to which it adheres.

The UK’s energy policies will not just be determined by whether Brexit is soft or hard, but also factors affecting its energy mix. The uncertainty is compounded by the disparate situations of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

The EU single market operates according to the “four freedoms”: goods, people, services and capital are all free to move across borders. A soft Brexit would mean the UK stays in the single market and adopts most of its related laws. A “hard” Brexit would entail a withdrawal from the single market.

The British government recognizes the many energy interdependencies between the UK and the EU and has promised that Brexit will change as little as possible on this count. However, it is unlikely the EU will allow the British to cherry-pick the rules to which it adheres. Brussels wants to make sure there are significant costs to exiting the EU, so as to deter other member states from following the British example.

Transformation strategy

Among European members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the UK remains the second-largest producer of oil (after Norway) and the third-largest producer of natural gas (after Norway and the Netherlands).

Still, it became a net importer of oil as far back as 2005, and of natural gas in 2004. Its oil exports declined from 1.8 million barrels per day (mb/d) in 2000 to just 0.6 mb/d in 2016. About 72 percent of its oil exports went to the EU (mostly Germany) that year. The UK is also a net importer of electricity – from France and the Netherlands.

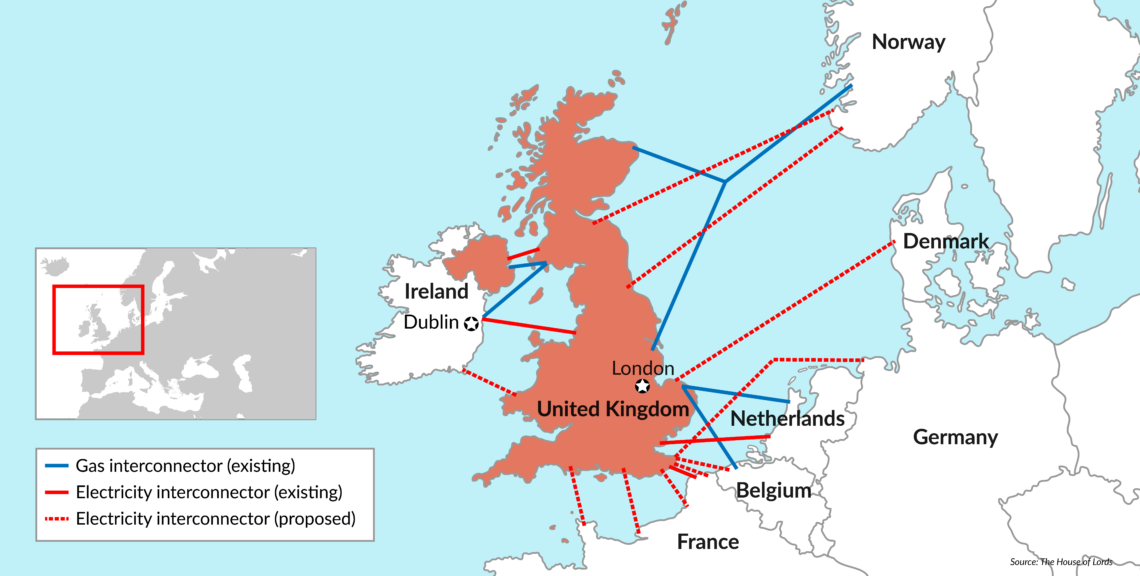

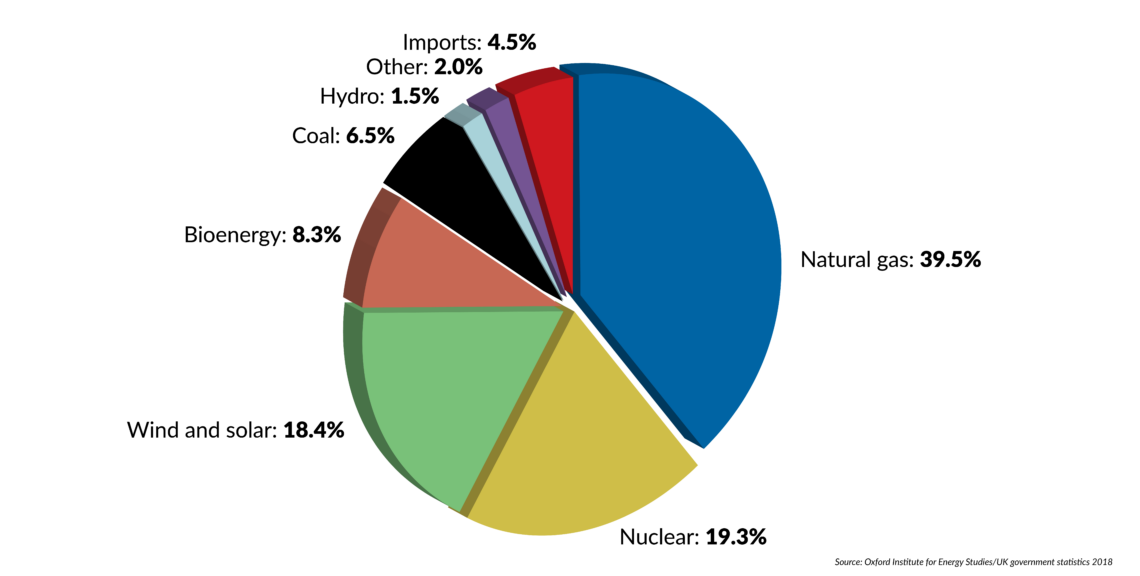

Natural gas production (mostly from offshore fields) picked up in 2014 and is growing at an average rate of 5 percent per year. Annual natural gas consumption is growing by about 7 percent per year. New investments and the discovery of new oil and gas fields in the North Sea could further boost production and exploration. In 2017, gas provided almost 40 percent of the UK’s electricity generation, but that was a slight decrease compared to the previous year, when the figure was 41.7 percent. In 2016, indigenous production made up just 47 percent of its entire gas supply. Some 77 percent of its gas imports came by pipeline (from Norway, the Netherlands and Belgium) and 23 percent via liquefied natural gas tanker. Norway and Qatar are the largest suppliers of imported gas, together accounting for 87 percent of the total. The UK also exports gas to Ireland via pipeline.

Facts & figures

Ireland's energy interconnectors

The use of renewables in UK power generation doubled between 2007 and 2016. Together with nuclear power, “clean” energies accounted for a record of 50 percent of electricity generation in 2017. As a result, the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions fell by as much as 4.8 percent in 2016 – faster than the EU average. The share of fossil fuels in the electricity mix is planned to drop to just 13 percent by 2035. However, clean energy investment decreased by 56 percent last year, following a 10 percent decline in 2016.

The UK now generates twice as much electricity from wind as from coal. The share of coal in the country’s primary energy consumption declined from 19 percent in 2012 to 6 percent in 2016. Britain’s last coal mine closed in 2015. By the end of this year, the UK will only have six coal-fired power plants, all of which are likely to close by 2025. Scotland’s power system is already coal-free.

The UK’s “clean energy strategy” of 2017 is focused on offshore wind power, increasing energy efficiency, unconventional gas (fracking) and continued support of nuclear power – despite renewables’ falling costs. A new generation of nuclear plants will have to replace the aging reactors due to be decommissioned in the coming years. Doing so will be expensive.

Facts & figures

The UK's electricity mix, 2017

Soft Brexit scenario

When the Brexit negotiations with the EU began in June 2017, British concerns focused on the potential impact European countries’ tariffs could have on its energy trade, as well as the employment of EU workers in the UK oil and gas industry. Over the past decade, increasing energy ties between the UK and other EU members have bolstered supply security for both sides by making cross-border trade easier, cheaper and more resilient.

The UK has played a leading role in developing the IEM. In 2016, the EU supplied about 12 percent of the UK’s gas and 5 percent of its electricity demand. Electricity imports are expected to grow faster over the next five years to meet the UK’s heat and power demand, so strengthening the energy ties between the EU and the UK will become even more important in the years ahead. It will become increasingly necessary for the two sides to improve efficiency by harmonizing regulations.

Supply risks in the gas sector may increase. Financing for new gas interconnectors and LNG-import terminals could be insufficient, and if the EU and UK do not work together, they may be unable to develop common preventive action plans or implement joint emergency procedures in case of disruptions. According to some estimates, the UK needs to secure some 180 billion British pounds worth of investment in its electricity system by 2020. The EU has several powerful funding sources, such as the European Investment Bank (EIB) and programs such as the Connecting Europe Facility (CEF), which supports investments in EU energy infrastructure (like gas and electricity interconnectors). The EIB is the world’s largest multilateral borrower and lender, with more than 90 percent of its loans going to EU member states. These sources cannot be replaced by programs from global financial institutions like the World Bank.

The costs of developing electricity generation could rise as UK utilities lose access to European financial support.

By 2022, electricity interconnectors with neighboring EU countries could meet about 35 percent of the UK’s peak electricity demand. These strengthen the security of the UK’s energy supply by providing flexibility and diversification.

The costs of developing assets for electricity generation could rise significantly as British utilities lose access to European financial support – probably even in the case of a soft Brexit. The country’s nuclear industry could also be hit with additional costs on the transport of materials and technology. The UK currently has eight nuclear power plants, which provide 20 percent of UK’s electricity demand and balance volatile production from renewables.

Those problems could be compounded by the UK’s post-Brexit immigration policy and challenges finding specialist energy workers and experts (for both the industry and government agencies). Any shortage of skilled workers such as engineers could slow the country’s energy transformation and the digitization of its energy sector, including construction of the GBP 20 billion Hinkley Point C nuclear plant and the rollout of smart meters for measuring end users’ electricity consumption.

Though most British energy experts support the UK remaining in the IEM, that outcome is unlikely, since the government is working to leave the single market and the jurisdiction of the EU’s Court of Justice. Even in a scenario where Brexit is soft but the UK still leaves the IEM, most energy experts fear trade will become less efficient, translating into higher energy prices for end consumers. They are asking for a longer transition period to adjust regulations, contracts, working practices and IT systems.

The UK will find it challenging to retain any influence on EU decisions regarding energy and climate policies. London led the charge for developing the single market, liberalizing EU energy policies and creating the internal energy market. It has clearly benefited from the participation in EU organizations and agencies.

If the UK leaves the IEM, trade will probably become less efficient, translating into higher energy prices.

The UK could gain associate membership or observer status in the European Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators (ACER) and the European Network of Transmission System Operators for Electricity (ENTSO-E) or Gas (ENTSOG). But none of this would give the UK a level of influence comparable to what it has now, as the experiences of other non-EU members, such as Norway and Switzerland, have shown. They are often excluded from working groups whose decisions have important implications for their national energy policies. To even achieve observer status, the UK may have to adopt IEM legislation and the energy acquis, taking the UK from a position of “rule-maker” to “rule-taker.”

Hard Brexit scenario

With a hard Brexit, energy trade between the UK and EU countries will become much more complicated. Adjusting for variations in regulations could result in higher costs for UK consumers. Estimates have shown that leaving the IEM could cost the UK as much as GBP 500 million per year between 2020 and 2025. The UK will also leave the EU’s Emission Trading System (ETS) after the current trading period expires in 2020.

The UK’s nuclear sector could be hit the hardest. Its materials transport takes place under the aegis of Euratom, which facilitates trade in nuclear materials and prevents their proliferation for military purposes. It also oversees a framework of cooperation agreements and research and development collaboration. In leaving the Euratom Supply Agency, the UK’s nuclear industry risks losing access to certain components. Purchases could become costlier. If the British government does not replicate EU regulations for the domestic market by March 2019, the UK may find itself unable to trade nuclear materials, goods and services.

The UK’s Office of Nuclear Regulations will also have to recruit and train inspectors and other technical experts. Many of them will be found in EU countries at a time of heightened demand – numbers are already low due to worries about the future of nuclear power. Though this problem would exist under the soft Brexit scenario, it would present an even more difficult challenge under a hard Brexit.

The UK’s nuclear sector could be hit the hardest. It risks losing access to certain components.

There are even more questions surrounding EU financing for British energy infrastructure, including new electricity and gas interconnectors with EU countries. If funding were to drop, the UK might not be able to afford the infrastructure necessary to guarantee energy supply security.

No deal scenario

If the EU and UK cannot come to an agreement for either a hard or soft Brexit, a no-deal scenario would ensue. Such an outcome would be the most frightening, because the uncertainties regarding investment, legislation and regulation would continue for the medium to long term. Although this scenario would not be the end of the world, the halt in both decision-making and investments would lead to even higher costs for both sides and threaten the energy security of both the UK and EU.

Strategic perspectives

Without the UK, a pro-market voice within EU structures, the bloc’s energy and climate policies could become more state-centric and interventionist. If the UK remains part of the IEM, this could pose challenges for the British government. While still being heavily connected to European infrastructure, the UK will not have any influence in the decision-making and unable to halt this trend. The impact on the UK’s energy market could be huge.

Cooperation with the EU’s IEM cannot be separated from the wider negotiated Brexit solution. Brussels would consider a special negotiation on energy and climate policies as “cherry-picking” and detrimental to EU cohesion and market harmonization.

The UK government’s white paper on Brexit favored the country remaining a participant in the EU’s single market. Doing so would keep the UK part of the IEM – which is increasingly integrating Europe’s gas and electricity market. Further integration with Europe contradicts the current British government’s policy.

Beyond Brexit, there are still big questions about the future of the shale fracking and nuclear power industries in the UK. If either were to fail, it would have major consequences for the UK’s energy mix and climate policies. In the end, the UK’s energy challenges mirror those of the EU partners it is getting ready to leave: ensuring an affordable supply while also decarbonizing the system.