Turkmenistan’s bid to link up with gas-hungry Europe

Turkey could play a decisive role this year in determining whether Russian natural gas reaches Europe or Turkmenistan becomes a bigger player in the trade.

© Getty Images

In a nutshell

- Europe and China have reduced Russia’s natural gas export options

- Turkmenistan’s Caspian Sea plan faces Russian, Iranian opposition

- Turkey is weighing whether to help Moscow or Turkmenistan

In late July 2023, Turkmenistan made waves by announcing it was ready to fundamentally redraw the map of natural gas infrastructure linking Central Asia and the South Caucasus with Turkey and onward to Europe. But whether it really will come to pass is a different matter.

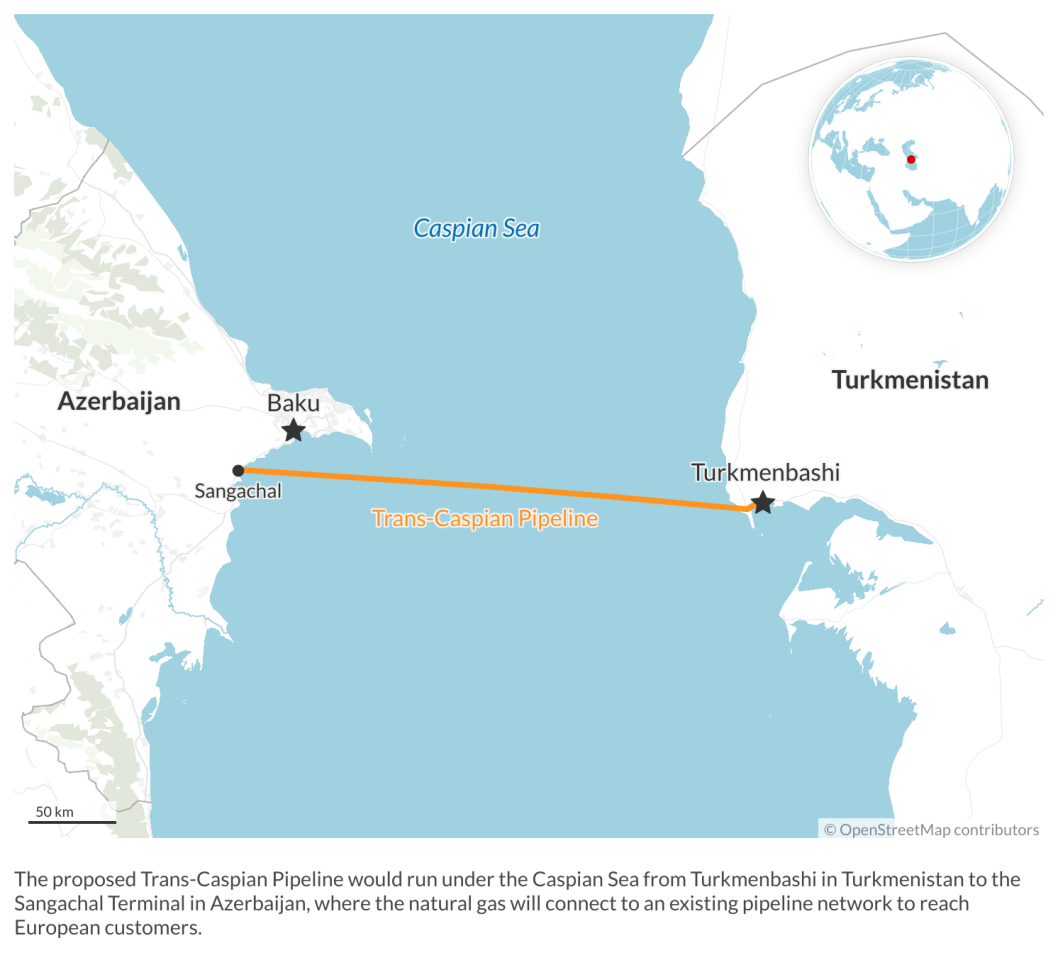

Turkmenistan, with only 6.3 million people, is a country with a long tradition of opacity and self-imposed isolation. The question of a Trans-Caspian Pipeline (TCP) across the Caspian Sea to Azerbaijan has been discussed off and on since the early 1990s, and nothing much has happened.

The reason why it has suddenly come into focus and is being taken quite seriously is directly linked to the war in Ukraine. At the time of its full-scale invasion in February 2022, Russia had a powerful grip on the European market for natural gas. The European Union imported 83 percent of its gas, and much of this came from Russia. In the third quarter of 2021, Russia’s share of the EU’s natural gas imports was 39 percent, but in the third quarter of 2023 it was just 12 percent.

Given that the EU chose not to sanction Russian gas, member states like Spain and Belgium have been able to substantially increase their purchases of Russian liquefied natural gas (LNG). Calls to close this loophole are growing. No matter what happens with LNG, pipelines remain the top conduit for Russian gas export, and in that domain, the outlook for Russia is not good.

Before the controversial construction of the two Nord Stream pipelines that pumped Russian gas to Germany via the Baltic seabed, the main route to Europe was a Soviet-era pipeline network through Ukraine and Belarus. According to a 2019 transit deal, Russian Gazprom may still pump more than 40 billion cubic meters per year via Ukraine, a trade that earns Kyiv up to $7 billion annually in transit fees. The main buyers remain Hungary and Austria, but Slovakia and Italy also take part.

Both Nord Stream I and II, as well as the path through Ukraine, may now be written off. Following their destruction by sabotage in September 2022, the Nord Stream installations are unlikely to come on stream ever again. Once Gazprom’s transit deal with Ukraine expires at the end of 2024, that route is also likely to be shut.

These developments cancel the lion’s share of Russian export capacity for Europe through pipelines, built at a significant expense and in defiance of strong opposition from the United States and some EU member states. The only remaining path is via the Black Sea to Turkey and into southern Europe.

The situation places the EU in a conundrum. As part of its strategy to diversify its supply sources away from Russia, it has taken steps to secure increased gas deliveries from Azerbaijan. According to a recent agreement, the volume of Azeri gas coming into European markets is to double by 2027, reaching 20 bcm per year. While this is a politically important signal, it will not have much impact on the flow of Russian gas. And it does not address the question of how Hungary and Austria will adjust when the flow of Russian gas via Ukraine is halted.

The key to what will follow is held by Turkey, which is 99 percent dependent on imported gas. It currently receives about 40 percent of that from Russia via the Blue Stream and Turk Stream pipelines across the Black Sea.

While the former is exclusively for Turkish use, the latter makes landfall in the European part of Turkey and supplies countries in southern and eastern Europe, like Greece, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Romania, Serbia and Hungary.

Read more by Stefan Hedlund

New masters in the South Caucasus

Uzbekistan may have another president for life

The fate of the Russian Far East takes on greater urgency

Turkmenistan’s vast natural gas reserves

The concern in some EU countries is that Turkey will accept Russian proposals to set up a joint hub for gas trade that would allow Gazprom to pump its gas into the Turkish mix. That was proposed by Russian President Vladimir Putin in the fall of 2022 when the Russians began to grasp that their other paths into Europe would be closed.

From the joint hub, Russian gas could be exported to European countries that might hesitate to purchase gas that is openly known to be of Russian origin. Thus far, the project has been bogged down in disputes over who would be in control. However, it does present a possibility for the Kremlin to maintain a substantial presence in the European gas market, albeit clandestinely.

That is where Turkmenistan enters the picture. With proven reserves of natural gas estimated at 19.5 trillion cubic meters by BP (formerly British Petroleum), the small country has the fourth-largest reserves in the world, after Russia, Iran and Qatar. Although much of the annual output from those fields is pumped to China, it is assumed that there is spare capacity for other markets.

Linked up with existing transport infrastructure in Azerbaijan, that capacity could provide sufficient volumes of gas for Europe to ensure that all Russian exports to that market may be terminated. There is only one snag, namely, getting the gas across the Caspian Sea. Although it has seemed impossible to get around that obstacle for over two decades now, the government in Ashgabat projects confidence that this time, it may and will be overcome.

Turkmenistan faces objections from Russia and Iran

In its July announcement, the Turkmen foreign ministry announced a momentous shift in the country’s energy export stance: “Turkmenistan, being committed to the strategy of diversifying energy flows, expresses its readiness to continue cooperation with partners in the implementation of the Trans-Caspian Pipeline project.”

It also addressed one of the hitherto main obstacles, namely, the fact that Russia and Iran had adamantly opposed the TCP. As the two leading powers among the five littoral states (along with Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan), their voices have carried weight.

Ashgabat, however, now seems ready to proceed in defiance of such objections. Voicing confidence that it could see no political, economic or financial factors standing in the way, it argues that the Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea that was concluded in 2018 does provide an adequate legal basis for the TCP to be built. This leaves the question of whether Turkmenistan will be both able and willing to carry out its plan.

In the Soviet era, gas that originated in Turkmenistan was known by default as “Russian” gas, and all infrastructure to pump it to markets went via the Central Asia Center (CAC) pipeline that runs from Turkmenistan via Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan to Russia. Following the breakup of the Soviet Union, Turkmenistan came into its own and embarked on a policy of diversification that challenged other actors to enter the game.

The response from Russia was to upgrade the CAC with a pre-Caspian pipeline that would hug the eastern shore of the Caspian Sea. By 2007, it was generally believed that in the intensifying competition over energy in Central Asia, Russia had emerged as the winner. The assessment proved to be premature.

Facts & figures

China asserts its interests to Russia’s detriment

While Russia was busy talking about building the pre-Caspian pipeline (to date, it has not materialized), China moved swiftly to advance its own interests. Following an agreement in 2006, it embarked on building the Central Asia-China system of pipelines that pumps gas into its eastern Xinjiang province. The first two lines were completed in 2009 and 2010, with the third finished in 2014 and the fourth still under construction. Although Turkmenistan is not the only source, with an annual capacity of 55 bcm, the Turkmenistan-China pipeline is the cornerstone.

The impact on Russia was severe. Having been deprived of access to the largest gas reservoirs in its former backyard in Central Asia, it also had to face the fact that China would have zero interest in building a pipeline linking it to the big Russian gas fields in Western Siberia.

Meanwhile, Western energy corporations were busy exploiting huge new offshore finds of hydrocarbons in the Caspian. A leading role was taken by BP, which joined with Azeri state-owned energy company SOCAR in developing the giant Shah Deniz gas fields. That development was strategically important in that it would be the first to bypass Russia in pumping gas to Europe.

The first step in what would come to be known as the Southern Gas Corridor was the Baku-Tbilisi-Erzurum (BTE) pipeline that takes gas from Shah Deniz via Baku onward to Tbilisi in Georgia and Erzurum in eastern Turkey. Also known as the South Caucasus Pipeline, it was opened in 2006.

The second step was the Trans-Anatolian (TANAP) pipeline built across Turkey, from Erzurum to the border with Greece. From its start of operations in June 2018, it has transported a total of 46 bcm, of which 22 bcm is for Turkey and 24 bcm for Europe.

The third and final step was the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) which connects with the TANAP at the Greek-Turkish border. Launched in November 2020, it traverses Northern Greece, Albania and the Adriatic Sea to make landfall in Southern Italy, where it connects to the country’s gas network.

The collapse of markets for Russian gas in Europe followed in the wake of the Chinese pushing it out of Central Asia. Russia has been upstaged in Azerbaijan by BP, and there are grounds to look at the Black Sea option as something of a last stand for Russia as an exporter of natural gas.

It will still have the Power of Siberia pipeline to China, but that business is heavily on Chinese terms, and it will have LNG, but that is minor. Getting access to the Southern Gas Corridor is vital for Russia. And this is where it gets interesting.

Scenarios

Two very distinct scenarios are possible.

Going ahead with TCP’s construction

Circumstances that speak in favor of building TCP range from a recent decision by the Turkish energy regulator EPDK to issue a 10-year license for the state energy company BOTAS to import gas from Turkmenistan and a joint decision by Azerbaijan and Turkey to double the annual capacity of TANAP from 16 bcm to 32 bcm, which could be done quickly. Under this scenario, the Southern Gas Corridor could be filled with sufficient volumes of gas from the Caspian Basin to lock Russia out.

TCP is not built

Alternatively, the TCP fizzles. Factors that speak in favor of this outcome are mainly related to uncertainties about how financing would be arranged and about how much spare export capacity Turkmenistan has. While Azerbaijan has said it is ready to accept the added gas flow, it will not contribute to the financing. It is unclear exactly how much Turkmen gas is exported to China, and there are plans underway for a five-year swap deal with Iraq that would see Turkmenistan export 10 bcm annually to Iran, which would then, in turn, export a corresponding volume to Iraq.

Given that both scenarios have Turkey as a clear winner, the outcome will be determined by how President Recep Tayyip Erdogan views the options. The odds are that he will be keen on developing the link with Azerbaijan, which needs the added input from the TCP to live up to its ambitions concerning Europe, and he will be keen on maintaining good relations with Russia, which speaks in favor of moving ahead with a joint hub for gas.

The real crunch goes beyond the commercial side of the hub. It concerns whether Turkey is ready to make good on proposals that TANAP be included in the hub. If Gazprom does get that access, then it will have secured a new lease on life as a supplier of gas to Europe. Several EU member states would be happy to see that outcome. However, Ankara is not anxious to make this gift to Moscow. It is much more likely to play the TCP card as a delaying tactic to keep the geopolitical concerns in a protracted limbo.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.