The CBDCs are coming: Should we worry?

The first central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) are debuting. Libertarian concerns aside, their potential for disruption in banking is considerable.

In a nutshell

- Central banks may want digital currencies to replace cash

- CBDCs offer politicians important advantages over “dumb” money

- Government control over citizens’ finances would only grow

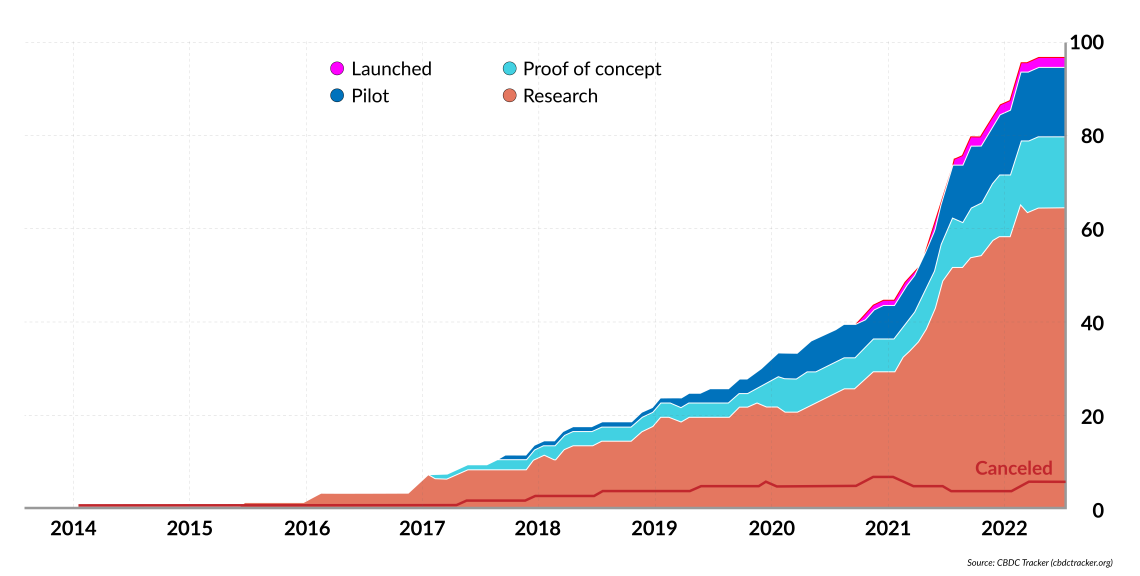

Although various projects have been in development for years, it was finally 2022 when central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) burst onto the scene and entered the public consciousness. We saw a surge of interest by central banks and many new practical steps being taken toward implementation. China is the front-runner with its e-CNY being rolled out, the United States has already launched a pilot program, Japan is set to launch its own in April 2023 and the eurozone is also playing catch-up. This race is expected to continue, with significant implications for the state and investors, savers and citizens.

So far, most Western pilot and development efforts are focused on “wholesale” CBDCs, only used in interbank settlements. However, “retail” CBDCs that could replace cash in the entire economy are the ultimate goal. Unlike cryptocurrencies that use blockchain technology, which is decentralized, transparent, tamperproof and ensures anonymity, CBDCs are centralized, traceable and directly issued and managed by central banks.

A threat to freedom – referring to what?

Most conservative-minded, liberty-loving and privacy-sensitive people have an instinctively hostile reaction against introducing CBDCs. Many arguments against them are entirely valid, and the fears are more than justified, as we will discuss later. However, before we summarily reject this new form of money and reflectively condemn it as “a direct threat to our freedom,” it is worth taking a moment to ponder this question: Sure, it is bad … but compared to what? To an ideal world where all individuals have absolute financial sovereignty and the freedom to choose any means of exchange or store of value they prefer – or to what we have now?

From this point of view, there are not too many entirely new concerns that a CBDC would raise that we are not already dealing with. Most of our banking activity and transactions are already digitized, automatically monitored and constantly screened. Banking secrecy is already practically extinct, transactions get flagged and blocked all the time and governments can freeze private accounts with worrying ease.

Harmful attempts to plan and regulate the global economy

So, if we do not have too much to lose, could we have anything to gain from CBDCs? It can be argued that there are possible positive outcomes we might expect to see from their wide adoption. We are not talking about the usual talking points that governments and central bankers like to repeat, like “financial inclusion” and combating “fraud and money laundering,” since these are all things they can do with the digital and regulatory tools they already have at their disposal. But there are other interesting angles to consider.

Facts & figures

Central banks’ growing interest in CBDCs

For one thing, a CBDC (technically being a liability of the central bank) would be considered legal tender, which would, for the first time, allow anyone to efficiently hold an “account” in legal tender instead of a bank liability, as is the case today. This fact alone can positively affect how people think about their bank deposits and help them understand that they are not deposits at all, but rather credit that they supply to their banks.

As a result, we could see significant numbers of ordinary citizens shifting away from banks and flocking to CBDCs. After all, CBDCs lack counterparty risk, given that a central bank can never default on obligations in the currency it issues. Apart from making bank runs a thing of the past, that transition would also likely change the banking system and arguably make it more robust than it is today.

Blockchain in shipping, more than a buzzword

Mass adoption of CBDCs would undoubtedly trigger a tectonic shift in the banking sector, and the potential outflows would mean that banks would have to evolve and adapt or perish. New business models will have to be developed. For example, focusing on credit is an obvious path forward, as banks have a lot of experience and expertise in giving out loans. It is not a stretch to envisage a scenario where tomorrow’s banks would instead manage and market “mutual funds” to investors based on different types of loans: from mortgages for the risk-averse to high-yielding payday loans for risk-tolerant clients. These loans would be held off the balance sheet and the risk would be the investors.’ Such a shift could lead to a banking system that is more stable and structurally sturdier, but also fairer, since it could render “bail-ins” and other such measures extinct.

‘Dumb’ vs. ‘smart’ money

There is a caveat to the argument that I made in the beginning, namely that almost all of the risks of a CBDC are risks we are already facing in our modern, digital banking system. That caveat was precisely the word “almost.” Because, unlike our current “digital” dollars and euros that are mere “0 and 1” representations of good old-fashioned pieces of paper, CBDCs can work as a direct policy transmission tool.

The “dumb” digital money sitting in our online bank accounts cannot be programmed to do anything that a physical banknote cannot, but that is not the case with their “smarter” successors. That is precisely what makes them so attractive to central banks and governments, but also what makes them so uniquely problematic for investors, savers and individual citizens in general.

There is a little anecdote that illustrates this rather well. At the height of the negative interest rate period, I was consulting clients unwilling to pay the penalty for saving and assisting them in storing physical banknotes in high-security facilities outside the banking system. This option had no counterparty risk, no duration risk, pretty much all conceivable and insurable risks were indeed insured, and the clients were still paying a fraction of the amount they would have lost to negative interest. Should CBDCs come to replace cash, investors and savers will no longer have that option. The central banks could easily build a “demurrage,” or a penalty-carrying clause, into the digital currency itself to ensure that everyone who holds it can either spend it or sit back and watch it evaporate.

The EU’s proposed regulation of markets in crypto assets

Of course, there are other use cases we can think of for expiring or otherwise programmable money. Given our recent experiences with “pandemic relief checks,” it is not that far-fetched an idea. Perhaps, if a recession is looming, central banks could transfer to literally everyone $1,000 that must be spent in the next few months or else it expires. What about other state payments, from pensions to disability and welfare benefits, that can only be spent on specific things or places? The possibilities are endless, and so are the reasons to fear that this shift would sound the death knell of any independence central banks still maintain from governments. The politicization of monetary policy would be complete, with all the dangers this entails.

Privacy is also one of the most talked-about concerns we cannot fail to mention. Naturally, officials and CBDC enthusiasts insist that adequate protections and reliable checks and balances would be baked into the system so that no law-abiding citizen would have anything to worry about. The astute reader might remember very similar assurances (“you have nothing to fear if you have nothing to hide”) being offered before every significant curtailment of banking secrecy, individual privacy and financial sovereignty.

Scenarios

While we are indeed already living with threats like these in our digital age, as mentioned before, this quantum leap is bound to exacerbate them by massively simplifying government attempts at overreach. It is also worth remembering that once a state acquires a new “tool” (or “weapon” if you have a flair for the dramatic), it never relinquishes it. Governments change, new laws are passed and crises and emergencies happen, so it is important to think ahead and to consider in what kind of hands this particular new tool could end up.

It might eventually turn out that all these concerns about privacy or power abuses were overblown. CBDCs might be built and managed just like their proponents promise. But even if reality proves different and we end up with a dangerous new kind of money, it will still be a danger that can be countered through simple freedom of choice. And that is where the real threat lies, not in introducing CBDCs per se but in the elimination of any other alternative in the process.