China’s European bridgehead

Hungary has become Beijing’s gateway to the European Union.

In a nutshell

- Unlike the EU and U.S., Hungary has no plans to decouple from China

- Chinese companies are expanding across the country

- Much will hinge on the outcome of the China-U.S. trade war

- For comprehensive insights, tune into our AI-powered podcast here

Hungary, a member of both the European Union and NATO, is increasingly looking eastward to counterbalance its reliance on the West. As long as it remains part of the Western alliance system, Budapest is a valuable partner for China, capable of acting as a mediator and delaying or vetoing anti-China resolutions.

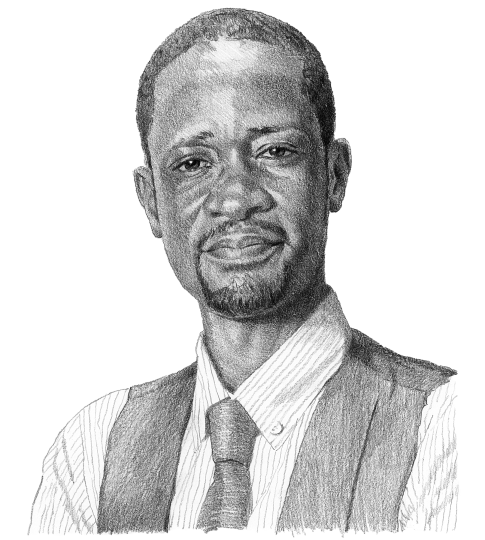

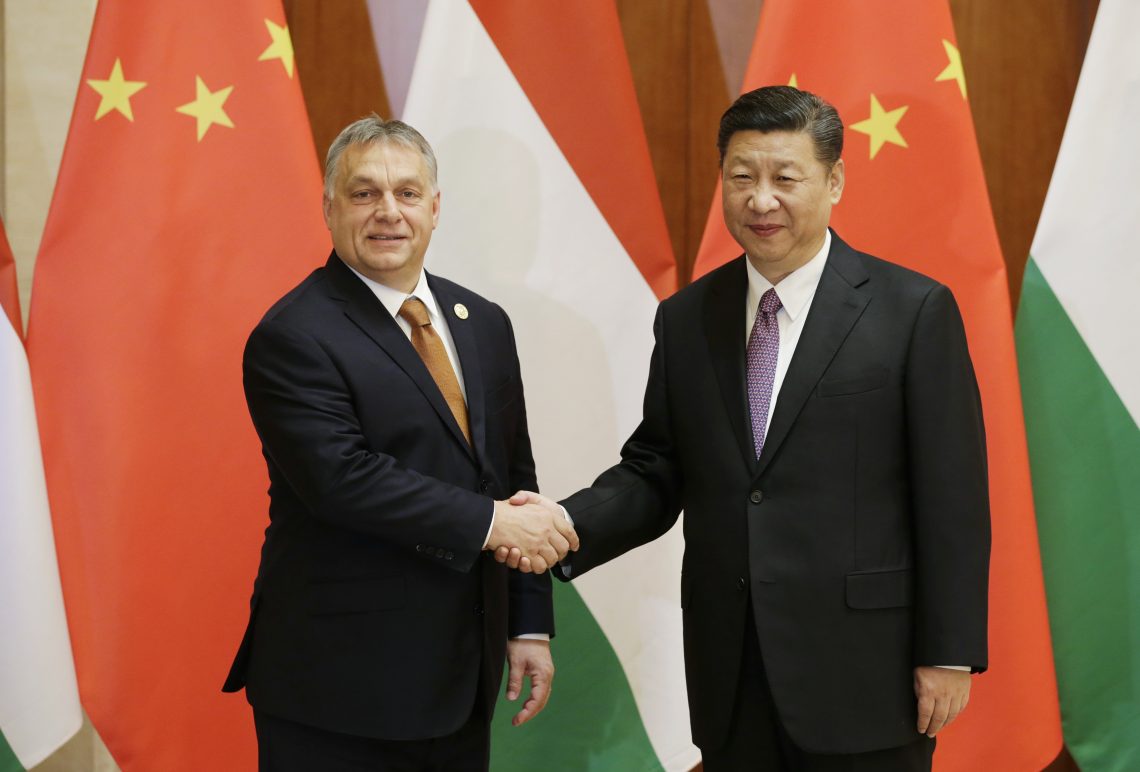

Hungary aims to reduce its heavy reliance on Western exports, which currently make up two-thirds of its imports, by deepening its cooperation with the emerging economic hub of Southeast Asia. This does not imply a reduction in trade with the West, but rather an expansion toward Asia. Japan and South Korea were previously the largest investors in Hungary, but in recent years China has taken the lead. In 2023, Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) in Hungary exceeded that of France and Germany combined. While Chinese capital and Confucius Institutes are met with skepticism elsewhere in Europe, they are warmly received in Hungary. Chinese President Xi Jinping’s state visit in May 2024 elevated bilateral ties to a strategic partnership.

China views Hungary – one of the few EU member states not to join the Clean Network Initiative and the only one where products from Russian-powered Chinese battery factories are supplied to German luxury carmakers – as a strategic foothold in Europe, if only for lack of better options. Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban maintains strong personal ties with Presidents Donald Trump, Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping, placing both himself and Hungary in a complex trilemma amid an emerging global tariff war.

Orban at the intersection of rival powers

Is it possible to maintain good relations with three rival world powers? In times of peace, perhaps. In a zero-sum tariff war, choices must be made. Like Russia, Hungary will ultimately have to pick a side: the Chinese camp or the American one. Some factors make that choice easier. President Trump cannot serve a third term, whereas Presidents Xi and Putin have removed term limits, positioning themselves as “forever” leaders. Meanwhile, the emerging BRICS+ economies offer more promising growth prospects than the stagnating, inflation-hit West. And unlike Washington and Brussels, Beijing does not tie its investments to political conditions such as anti-corruption efforts or rule of law benchmarks.

As Europe’s longest-serving head of government, Prime Minister Orban has long cultivated close connections with all three leaders. He was the only Western leader to endorse Donald Trump in both 2016 and 2024. In November 2009, he met with President Putin in St. Petersburg, and a month later, in December, he held talks in Beijing with then-Vice President Jinping.

The history of Hungarian-Chinese relations

Hungary, a former member of the Soviet bloc, was the first country to recognize the People’s Republic of China in 1949. In 2015, it became the first EU member state to join the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which now includes around 150 participating countries. China initially engaged with Hungary through the 16+1 framework for cooperation with Central and Eastern Europe. The relationship further deepened under Hungary’s Eastern Opening policy. During the Covid-19 pandemic, Hungary purchased 5.2 million doses of Sinopharm vaccines, along with protective equipment and ventilators, from China.

Chinese leadership values Hungary’s role as a connectivity hub, as demonstrated by high-level visits to Budapest in 2011 and 2024. In the 75th year of diplomatic relations, the bilateral relationship was elevated to an all-weather strategic partnership. Prime Minister Orban is a regular visitor to Beijing. Most recently, he attended the BRI Forum in October 2023 and conducted a peace mission in July 2024 that took him to Washington, Mar-a-Lago, Brussels, Moscow and Beijing.

Facts & figures

Infrastructure development

The Belgrade-Budapest railway, a key segment of the BRI corridor stretching from Greece’s Piraeus to Germany’s Duisburg (Europe’s largest inland port) is being partially constructed by Hungarian firms, financed through a $2 billion Chinese loan. The project has faced two main criticisms: first, that the Hungarian section is being built by a company owned by Prime Minister Orban’s childhood friend, Lorinc Meszaros; and second, that some projections estimate a break-even point in nearly 1,000 years.

Confidence in the initiative has also been shaken by a fatal incident on the Serbian side, where the roof of the Novi Sad station – renovated by Chinese contractors – collapsed, killing 16 people and sparking ongoing protests. The Hungarian government defends the project by arguing that only Mr. Meszaros’s firms have the capacity to manage an undertaking of this scale, and that offset investments, such as the BYD factory and the planned fulfillment center at Budapest Airport, will accelerate the loan’s return.

The V0 rail ring road, originally planned with a $2 billion Russian loan, is now expected to be financed through Chinese lending, alongside the high-speed rail line connecting Budapest’s city center to the airport. A challenge with Chinese rail projects remains the incompatibility between Chinese safety and signaling standards and those of the EU, which may result in certain lines being designated as “private railways.” However, Hungarian construction sites are becoming reference projects for adapting Chinese infrastructure to EU standards.

Seven Chinese cities are connected to Budapest by 21 weekly flights, with the Zhengzhou and Shenzhen airport cargo terminals already operational. Plans are underway to establish a China Terminal at Liszt Ferenc Airport, intended to serve as a European hub for a Chinese airline. The newly established Sino-Hungarian carrier, Hungary Airlines – which launched operations at the end of 2024 – is also expected to participate in cargo transport, with an initial fleet of 100 Boeing 737 Max aircraft. However, President Trump’s tariff measures have prompted China to suspend Boeing purchases, casting uncertainty over the fleet’s composition.

Hungary has been exempted from sanctions on Russian energy, making it an attractive industrial location in the heart of Europe with a steady supply of affordable energy. Taking advantage of this, battery factories from Japan (Toyo Ink), South Korea (Samsung) and China have established operations in the country. One major example is Chinese company CATL’s $6 billion investment in Debrecen, next to BMW’s new electric vehicle (EV) factory, creating a win-win situation for both German and Chinese companies. Several European countries competed for BYD’s 5 billion-euro factory in Szeged, but Beijing ultimately chose Hungary – one of the few EU members, along with Germany, that opposed the bloc’s tariff on Chinese EVs.

Thanks to strong Sino-Hungarian relations and growing resistance to Chinese companies in Western Europe, BYD decided to relocate its European headquarters from the Netherlands to Hungary. The arrival of Chinese battery factories has sparked controversy in some local communities, but protests have subsided following rising property values and assurances of compliance with EU standards. Water demands are being addressed through new canals and grey water recycling systems, while labor shortages are being filled by migrant workers from Ukraine, the Philippines and other Far Eastern countries, in line with the conservative Hungarian government’s strict approach to migration.

Huawei established its Europe Supply Center in the Hungarian city of Pecs in 2009. Hungary’s refusal to join President Trump’s Clean Network Initiative also paved the way for the Chinese tech company to open an R&D center in Budapest in 2020. In October 2023, telecom cooperation deepened when Hungarian firm 4iG signed a strategic agreement with Huawei in Beijing to develop cloud and artificial intelligence services. Huawei now operates a separate data center for Chinese and Asian companies in the region.

Hungary has also shown interest in Huawei’s AI-based facial recognition system, which has been in use in Belgrade since 2019. While EU law prohibits the use of such tools for identifying political protest participants, Hungarian authorities deny any plans for such use. Under a 2023 Sino-Hungarian internal affairs agreement, Chinese police are entitled to joint patrols in Budapest’s Chinatown and tourist areas.

Diplomatic ties

There are Confucius Institutes at four Hungarian universities, a cultural center in Budapest, and Chinese medicine is taught in Pecs. The first European Fudan University campus was planned for Budapest, financed by a $1.5 billion Chinese loan, and intended primarily to train engineers and doctors for Chinese companies operating in Europe and the region. The project faced opposition from the liberal leadership of the capital, and as Sino-European relations deteriorated, it was shelved. A student town is now being built on the site, which could serve as an Olympic village in 2036.

As China closes the gap with the West, it has become a systemic rival, prompting increasingly critical stances from both the U.S. and the EU. The Biden administration already viewed Chinese EVs and digital products as national security threats, leaving little room for compromise. While the U.S. pursues a policy of decoupling, the EU has adopted a more moderate de-risking approach aimed at lowering exposure while preserving economic cooperation.

More on Hungary

- Hungary’s realpolitik on Russia

- Peter Magyar’s rise is reshaping Hungary’s political landscape

- A year of heavy political turbulence in Hungary

Tensions continue to grow. The European Parliament has yet to ratify the EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment signed in December 2020. Meanwhile, individual actions by Baltic states – particularly Lithuania’s 2021 decision to upgrade the Taipei Office to the Taiwanese Representative Office – have provoked Beijing, which temporarily removed Lithuania from its customs registry. Some of Ukraine’s supporters are also pressing China to rein in Moscow by applying economic and political pressure. At the Central European Summit, U.S. envoy Robert Palladino warned allies against deepening ties with China, especially in high-tech sectors, citing risks to national sovereignty.

However, America has yet to offer its allies a compelling economic alternative to Chinese investment and technology. Whether these risks escalate or ease will depend largely on the trajectory of the U.S.-China tariff war.

Scenarios

More likely: Hungary maintains close economic ties with China

Hungary is expected to continue cooperating with China in 5G technology and EV manufacturing despite disapproval from the U.S. and EU. If the current governing parties win the 2026 elections, Hungary would likely maintain its position as an outlier within the West, resisting broader de-risking and decoupling trends, just as it has with economic and energy sanctions against Russia.

Less likely: Hungary gradually aligns with Western de-risking policies

Hungary could shift from connectivity to cautious distancing, depending on pressure from the White House and the evolution of U.S.-China and EU-China relations. This would include limiting Chinese acquisitions and reducing the use of Chinese high-tech in strategic sectors. For example, over the next five years, Chinese components might be phased out of Hungary’s 5G network, including its core infrastructure, following the German model. If the opposition wins the 2026 parliamentary elections, they are likely to move in this direction.

Contact us today for tailored geopolitical insights and industry-specific advisory services.