Italy’s risky relationship with China and Europe’s future

When Italy became the largest EU country to sign a memorandum of understanding on the Belt and Road Initiative, it put Italy-China relations in the spotlight. So far, Italy has gained little from the partnership, and risks getting caught in the crossfire of U.S.-China tensions.

In a nutshell

- Italy is the first G7 country to sign on to China’s BRI

- The move has complicated Rome’s relationship with its allies

- Greater technology cooperation could provoke a crisis

Over the past year, governments in Germany, France and the United Kingdom have become more circumspect about the challenges China poses to their interests and values. Yet they are also reluctant to risk their productive relationships with China over these concerns. With issues like Chinese investment, cybersecurity threats and human rights dominating headlines, no European government has found a stable balance among the considerations.

By signing onto China’s Belt and Road Initiative last spring, Rome has leaped into the spotlight of European China policy. How Italian policymakers resolve these dilemmas offers clues to Europe’s future direction on such issues.

European powers and China

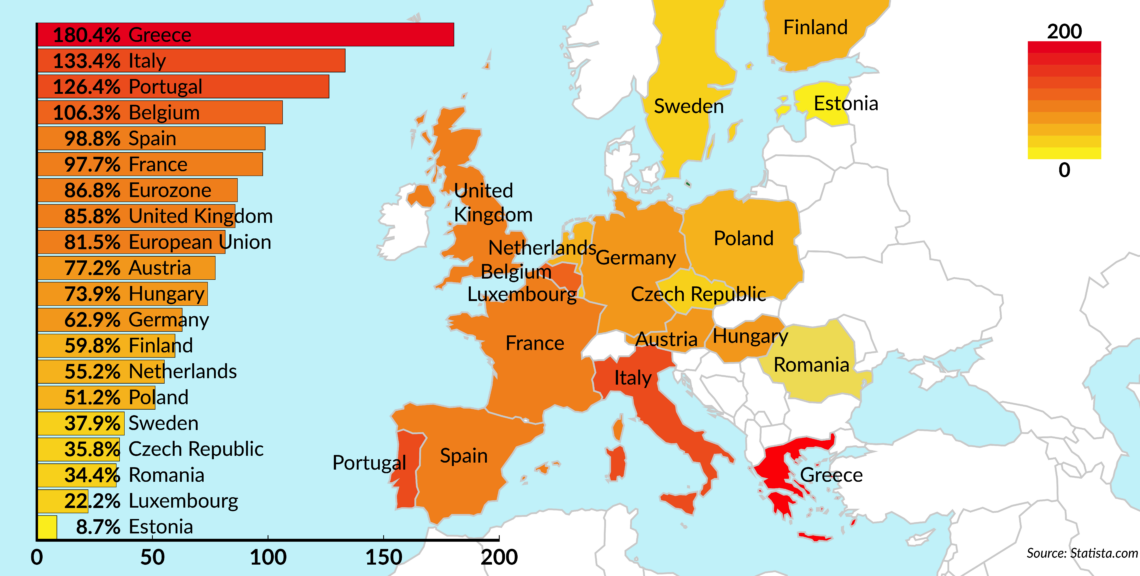

China’s relations with Germany and France remain essentially unchanged from where they stood 18 months ago. The same dynamics are in play. The European Union is China’s largest trading partner and China is the EU’s second-largest. Europeans have major investments in China. There is declining but active Chinese investment in Europe, and European governments have acute security problems closer to home, like those posed by Russia’s assertiveness.

That France and Germany continue to prioritize close ties with China is reflected in their highest-level diplomacy. Chinese President Xi Jinping visited Paris in March 2019, and French President Emmanuel Macron returned the favor in November. On his second trip to China since being elected, he oversaw the signing of $15 billion in commercial deals. German Chancellor Angela Merkel also visited China in 2019 – her 12th since 2005, also accompanied by a large business delegation. Both leaders have stressed the positive side of their nations’ relationships with China, for example, on Iran and climate change.

The most significant development in Europe-China relations over the last year has been the newfound prominence of Italy in the public debate.

When possible, France and Germany have tried to present a common front to the Chinese. When President Xi visited Paris in March 2019, the French arranged for a joint meeting with President Macron, Chancellor Merkel and European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker. When President Macron visited Shanghai in November, he brought with him a German minister and an EU commissioner. This show of unity could not have been lost on the Chinese.

While the UK’s economic ties with China remain robust, diplomatically, it has been in a holding pattern, awaiting the conclusion of Brexit. The Conservative victory in December 2019 should resolve this and allow London to get on with its foreign policy agenda – as well as fully test its new capacity for trade policy. The UK begins its post-Brexit approach with China as its third-largest trading partner after the United States and the EU – by some considerable distance. The UK remains the leading European recipient of Chinese investment – although as in trade, the totals pale in comparison to those from developed countries like Japan and the U.S. Still, the UK will be eager for post-Brexit economic successes with virtually all partners, including China.

More than Paris and Berlin, London will need to balance this economic interest against its relationship with the U.S. and Washington’s more hawkish view of China. UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson has at times sounded eager to engage China, having described his government as “very pro-China” and “enthusiastic” about China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and most recently publicly offering the benefit of the doubt to the Chinese telecommunications giant, Huawei.

Facts & figures

All three have expressed critical views of China as well. France has interests in the Indo-Pacific that naturally carry the seeds of tensions. It continues to conduct freedom of navigation operations that risk Chinese ire, in both the South China Sea and the Taiwan Strait. Prime Minister Johnson has also expressed concern for freedom of navigation in the South China Sea, both rhetorically and materially with the deployment of the Royal Navy there. All have human rights concerns.

Italy-China relations

The most significant development in Europe-China relations over the last year has been the newfound prominence of Italy in the public debate. Italy shocked capitals in Europe and Washington when, in March 2019, it became the first G7 member to sign a memorandum of understanding (MoU) on the BRI.

It was the first, populist-right government of Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte that initiated this new, cozier Italian relationship with China. Aside from facilitating more investment, the policy has highlighted two other prominent China policy considerations – communications technology and human rights. In each of these three areas, a fierce debate is on in Italy.

This debate is playing out against a backdrop of positive Italy-China relations that goes back to the first government of Prime Minister Romano Prodi (1996-1998, 2006-2008). In fact, today, Mr. Prodi promotes good relations between his country and China in a manner similar to that of Jean-Pierre Raffarin, Gerhard Schroeder and David Cameron in France, Germany and the UK, respectively. While Mr. Prodi himself may be of advanced age, one of his successors – Italy’s youngest-ever prime minister, Matteo Renzi (2014-2016), is of a similar mind.

Prime Minister Conte’s second government, aligned to the center-left, took power in September 2019. It should be no surprise that while perhaps recalibrating ties with China, it is not breaking them. The MoU is still very much alive.

Italy’s role in the BRI

The story of Italy’s commitment to the BRI is a fascinating case study in Italian governance. It was heavily driven by the dreams of one man: former Undersecretary of State for Economic Development Michele Geraci. An engineer by training, Mr. Geraci was brought from obscurity into the first Conte government by the right-wing Lega (the League) party. He made his way to influence in a Ministry of Economic Development headed by Lega’s populist coalition partner, the Five Star Movement (M5S).

Mr. Geraci’s single-minded focus on China and a relatively simple calculation on the part of M5S that China could help it fulfill its expensive election promises proved fertile ground for closer Italy-China relations. Mr. Geraci has since left government service, but Luigi Di Maio, under which he served, is now Italy’s foreign minister. Mr. Di Maio’s chief of staff is Ettore Sequi, a recent ambassador to China and supporter of closer Italy-China relations.

For China, the MoU was a major diplomatic coup. Prior to that deal, 22 European countries had signed onto the BRI project, but they were small. The largest of them, Poland, has an economy only a quarter of the size of Italy’s. Italy, by contrast, is the third-largest economy in the European Union (excluding the UK, which is on its way out).

Beijing has pocketed its diplomatic win and moved on. The Italians have been left with the worst of both worlds: no significant gains, yet provoking allies’ concern.

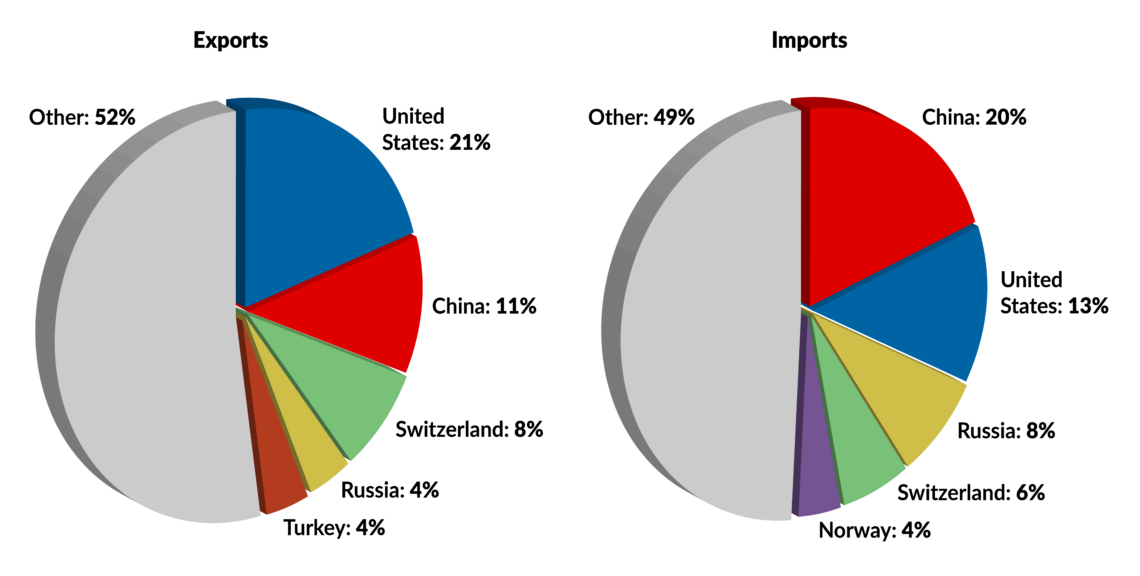

With its move, the Italian government calculated that it could steal a march on Germany, which draws much larger shares of Chinese investment despite not formally signing on to the BRI. It was also hoping to obtain more third-party partnerships and improve China’s disposition toward Italian exports and investment.

While it is true that the language of the MoU is much more nuanced (thanks to the bureaucrats tasked with negotiating it) than it is often portrayed, none of its expected payoffs have materialized. Essentially, Beijing has pocketed its diplomatic win and moved on. The Italians have been left with the worst of both worlds. They have achieved no significant material gains (investments) even as they have provoked the concern of their allies in the EU and in Washington.

The most likely path for Italy going forward is continuation of the status quo. It has no other good options. An eventual payoff from China cannot be excluded. In 2018 alone, before the BRI partnership, according to the American Enterprise Institute’s China Investment Tracker, China’s Italian investments were comparable to its investments in France. Italy is also caught in the crossfire of the U.S.-EU trade war in a way that is deeply damaging to the small and medium-sized companies central to its economy. It needs the China market. It can only stick it out with China and double down on its relationship with Brussels to help insulate it from the resulting criticism.

Huawei and 5G networks

No China-related issue is roiling European capitals and Washington like the role of Huawei in the build-out of their national 5G telecommunications networks. Italy is no different. Like in Germany and the UK, Huawei is already deeply embedded in Italy’s current network. As with Berlin, London and Paris, Italy is officially unconvinced of the threat Huawei poses.

To cope with this situation, Italy just months ago adopted a very advanced legal framework for vetting investments in cyberspace. It revolves around what is called the government’s “golden power.” This is the government’s authority to step in to veto otherwise legal foreign investments in critical infrastructure and assets that might jeopardize national security. The government is in the process of finalizing the regulations and procedures to fully exercise this authority in the area of telecommunication networks.

As if to support this cautious approach, on December 11, 2019, Italy’s parliamentary intelligence oversight committee (COPASIR) released a report warning against the inclusion of Chinese companies in the buildout of 5G.

Italian telecom providers have moved ahead with Huawei to establish several ‘test beds,’ that can be scaled up within a year.

On the other side of the ledger, Italian telecom providers have moved ahead with Huawei to establish several “test beds,” that can be scaled up within six to 12 months. There are also rumors – denied by the government – of major deals pending between Huawei and Italian telecom service providers. The government emphasizes that the new cyberlaw provides retroactive authority to revoke any deal or expansion at a later date. It has made this clear to the business sector. Such warnings, however, could prove insufficient if business determines moving forward is worth the risk of cancellation.

Facts & figures

Italy’s legal framework for dealing with telecommunications technology plays neatly into Brussels’ strategy, both with regard to investment screening and 5G networks. In particular, this October, the EU released a risk assessment on the security of 5G networks that highlighted, among other threats, that of non-EU state or state-backed actors. By the end of this month, the commission plans to publish a list of recommended mitigation measures. This is happening even as national capitals conclude their own new laws to deal with the dilemma (France) and others (Germany and the UK) are engaged in contentious debates over the same issue.

On 5G, Italy reinforces Europe’s instinct for compromise. All concerned are trying to create legal frameworks that can safely accommodate Huawei’s participation, or at least, not explicitly rule it out. Rome will do its best to coordinate with the EU and NATO member countries so as not to move too far ahead of them.

At the same time, the consumer and commercial interest is intense and on a timeline of its own that could outrace government efforts to control the rollout. If Huawei becomes a part of Italy’s 5G network outside of coordination with allies – and against dire warnings from Washington – it could provoke a crisis in its alliance with the U.S.

Human rights

The current Conte government – and especially its foreign minister – are not eager to test relations with China over human rights issues. What has been interesting are the efforts of the Italian Parliament to step into the breach to provide the necessary leadership.

Parliament will coordinate its own positions when it believes the government is not sufficiently active.

This has been most vividly demonstrated in the case of Hong Kong. In November, frustrated over the Foreign Ministry’s weak response to troubles in Hong Kong, the Italian Senate held a bicameral leadership-approved video conference with democracy activist Joshua Wong. Simultaneously, hearings on the topic were being proposed in the lower house. When the idea of hearings was voted down by the Foreign Affairs Committee, two of its members, Maurizio Lupi (from the Us with Italy party) and Lia Quartapelle (from the Democratic Party) moved forward with a resolution supporting the protesters. The furious reaction from the Chinese embassy to the Senate-initiated Joshua Wong gathering propelled the members of the committee to approve the resolution.

This may be the model on such China-related issues going forward, from Xinjiang detention camps to Taiwan. Parliament will coordinate its own positions, in cooperation with allies in government and in Brussels, when it believes the government is not sufficiently active. Whether the government is pressured into it, or whether parliament acts on its own, Italy will be heard on these values issues.

Scenarios

Italy is a unique political environment made all the more so by the triumph of the M5S – a party that, befitting its populist roots, is quite flexible on matters of ideology. (It has made a sea change on its views of China.) Italy, however, is also deeply embedded in European values and political traditions and part of European-wide political networks. It has a highly developed economy as well.

Its response to the rise of China will be a difference of degree from those of Germany, France and the UK – not a difference in kind. As such, the policies it pursues toward China will reflect broader trends and likely outcomes throughout developed Europe.