China is making waves in the Pacific

The United States’ neglect of island nations in the Pacific has given China an opening, potentially harming regional security.

In a nutshell

- Washington has done little to counter Beijing’s growing reach

- Western allies Australia and New Zealand could face isolation

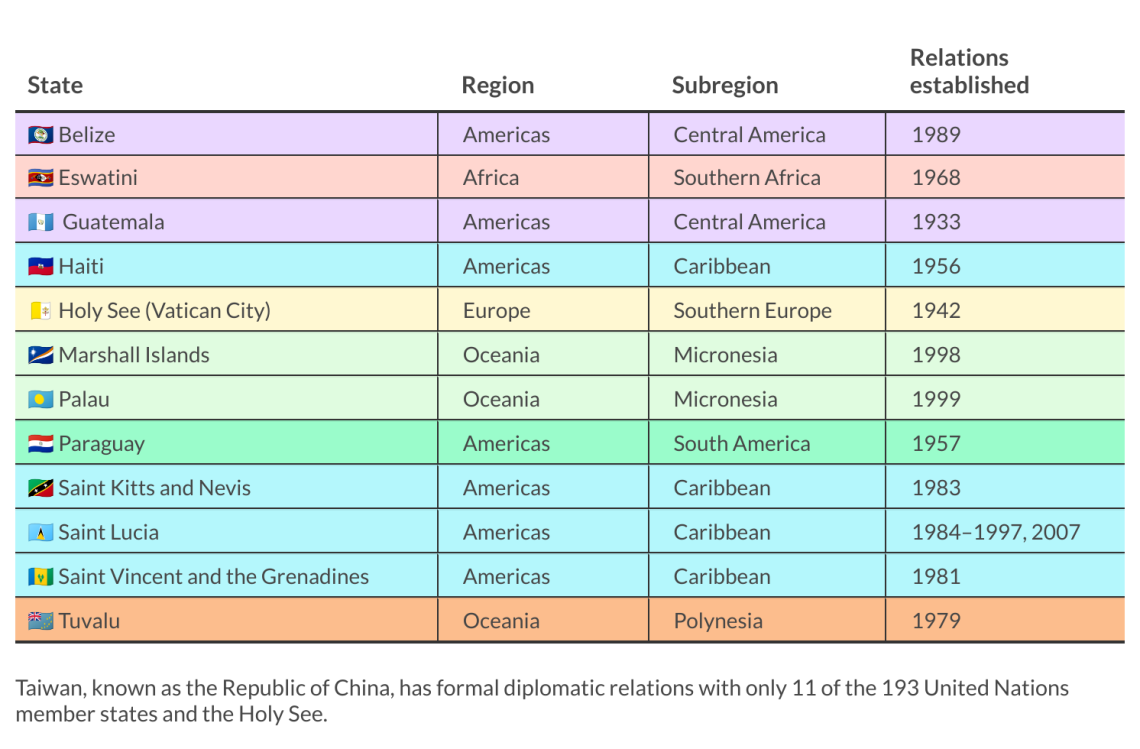

- Only three Pacific islands have diplomatic relations with Taiwan

At the height of World War II, the United States Navy built an airstrip on the now-island nation of Kiribati, more than 2,100 kilometers south of Hawaii in the central Pacific. Situated on Kiribati’s Canton Island, the airfield served as a vital refueling and staging base for flights between the U.S. and Australia, helping to ensure that allied Pacific nations were neither surrounded nor cut off from supplies by hostile forces.

Eight decades later, that strategic airstrip could become the property of China, which since 2021 has been conducting feasibility studies for its upgrade.

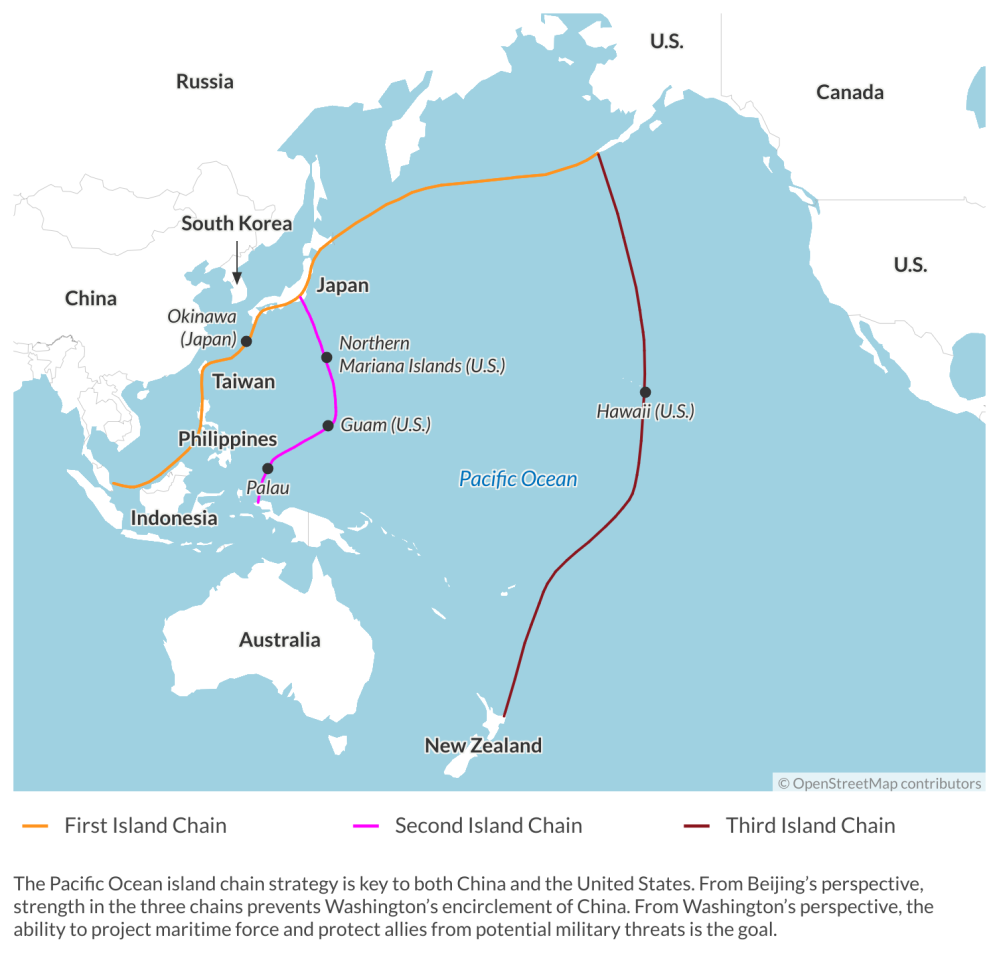

The potentially stunning twist of fate in Kiribati reflects a wider set of dynamics at play in the Pacific islands, where decades of American policy neglect have opened the door to Beijing’s attempted military expansion. Should it persist unabated, China’s military presence in the Pacific islands could undermine regional security by extending Beijing’s might to the Second and Third Island Chains, bringing the People’s Liberation Army closer than ever to American and Australian territory. Washington will need to expand its diplomatic presence in the Pacific islands to prevent them from becoming another critical flashpoint in the Indo-Pacific.

Island hopping with Chinese characteristics

China’s interest in Kiribati did not materialize out of thin air. The nation of 120,000 people is a collection of 33 equator-hugging islands that gained independence from the U.S. and the United Kingdom in 1979. Kiribati has an exclusive economic zone of 3.5 million square kilometers.

China’s interest in the island nation is also just one example where, over the past decade, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has increased and expanded its influence across the Pacific by courting local elites, forging ties with regional institutions and boosting regional investment.

In Solomon Islands, for instance, China has provided money to so-called Constituency Development Funds (CDFs) that have been used by the country’s pro-CCP Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare to induce parliamentarians to pursue pro-China policies. De jure, CDFs are public development funds made available to members of parliament to pursue development initiatives in their constituencies. De facto, they are legal slush funds. Last year, Mr. Sogavare used such funds to pay off 39 of 50 parliamentarians – enough to amend the constitution and postpone elections that were planned for 2023. Until 2019, when Solomon Islands switched its recognition from Taiwan to China, Taiwan had also funded CDFs.

More by Aleksandra Gadzala Tirziu

Peak China

Rising tensions along the Indian-Chinese border

China, Latin America and the new space race

Elsewhere, in Tonga, Chinese enterprises have invested in water supply projects, fisheries and equipment for local police. Beijing has also built St. George Palace, a $11 million office block that houses the Tongan government’s premier and its ministers. As of July, Tonga owes two-thirds of its external debt of some $430 million to Beijing. In Palau, Chinese security services have attempted to infiltrate the country’s media environment, so far unsuccessfully. In 2017, China attempted to pressure the country to switch its diplomatic recognition by cutting off Chinese tourism. Palau has held firm and, together with the Marshall Islands and Tuvalu, is one of only three island nations in Oceania that still have full diplomatic relations with Taiwan.

On the heels of the January 13 election in Taiwan, Nauru, a tiny island country in Micronesia, decided to switch its diplomatic recognition from Taipei to Beijing. The timing of the switch was likely carefully calculated. Taiwan had previously failed to meet Nauru’s requests for some $80 million in aid – a gap that Beijing was more than happy to fill. With the switch, only 11 members of the United Nations and Vatican City have full diplomatic relations with Taipei.

China’s efforts in the Pacific have tended to follow a predictable pattern. Beijing first establishes a commercial foothold in a nation, buttressed by Chinese nationals who, under the provisions of China’s 2017 National Intelligence Law, are legally obligated to support CCP intelligence operations. Beijing’s commercial interests target key industries or pursue prestige projects, like St. George Palace. Such outlays are also often accompanied by projects of strategic value for Beijing, such as ports, airports or digital infrastructure. The aim is to secure strategically located real estate that might allow Beijing to project power beyond America’s westernmost defenses.

Facts & figures

Solomon Islands enters into security pact with Beijing

In April 2022, Solomon Islands signed a security pact with Beijing that, among other provisions, allows for the deployment of CCP police, People’s Liberation Army (PLA) troops and “other military personnel” to maintain social order and protect Chinese commercial and national interests. That agreement was followed by another, signed in July of 2023, for heightened cooperation in “law enforcement and security matters.” Like many Pacific island nations, the country does not have its own military and depends on its police for security and defense. This has made Pacific police units key targets of CCP influence operations – while CCP police serve as influence agents.

Beijing’s focus on law enforcement partnership is prevalent throughout its various policy documents and pronouncements, such as its “China-Pacific Island Countries Common Development Vision.” It was proposed by Foreign Minister Wang Yi on his Pacific tour of islands in May and June of 2022. Among other issues, the vision stressed law enforcement cooperation including “immediate and high-level police training.” Its corollary, the “China-Pacific Island Countries Five-Year Action Plan (2022–2026),” proposed ministerial-level dialogues on police cooperation.

Neither the vision nor the action plan was accepted by island nations, yet Mr. Wang’s timing in submitting them suggests that was likely not the point. In advancing the notion of more institutionalized law enforcement cooperation, he likely aimed to plant the proverbial seeds among receptive parties so that they might germinate over time. In the Pacific islands, as elsewhere, China plays the long game.

Speaking at the Second Ministerial Dialogue on Police Capacity Building and Cooperation Between China and Pacific Island Countries in Beijing in December, Minister of Public Security Wang Xiaohong said China stands ready to work with partner island nations to “build a closer community with a shared future in terms of security.” Delegations from Tonga, Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea, the Cook Islands, Kiribati and Solomon Islands attended the dialogue.

Beijing maintains it has no intention of translating its fixation on Pacific islands’ security into infrastructure such as military bases. Yet its track record and ambitions suggest otherwise. In Djibouti, Cambodia, Pakistan and Sri Lanka, China has undertaken major infrastructure projects that have given it access to strategically significant port facilities. And as it has shown in Africa, where supposed peacekeeping missions have morphed into military operations, or in the South China Sea, where it has claimed and militarized artificial islands, China is adept at masking its intentions while expanding its footprint.

Remembering the map

Even in the unlikely event that the CCP would forgo establishing military bases in the Pacific islands, its police presence and that of Chinese-trained local law enforcement would likely provide it with the manpower necessary to stymie any U.S. plans to move forces into the region, keep Australia and New Zealand boxed in, secure maritime communication lines and increase intelligence collection on allied forces. China’s security presence in the Second and Third Island Chains would also place it near Australian and U.S. territory, notably Guam, which is 1,300 kilometers northeast of Palau

In December 2022, Beijing for the first time sailed its aircraft carrier Liaoning close to Guam and held military drills in its western waters. Chinese state media noted the operation “showed that the Chinese carrier is ready to defend the country against U.S. attacks launched from there, including military interference attempts over the Taiwan question.”

In March 2023, Chinese-linked malware infiltrated critical infrastructure on the island, including that used in maritime operations and to communicate with the U.S. mainland. Similar attacks have been launched against water utilities in Hawaii. Guam is America’s westernmost territory. It is home to the U.S. Navy’s sole submarine base in the Western Pacific, to Andersen Air Force Base – the only base in the Western Pacific capable of servicing heavy strategic bombers – and to more than 20,000 American troops. In the event of a Chinese attempt to take Taiwan by force, it would play a critical sustainment, logistics and transit role for the U.S. and its allies.

Yet for the past several decades, the Pacific islands have not been a focus for U.S. foreign policy. In the Pacific, the concern has largely been with the First Island Chain – Japan, Taiwan, Indonesia and portions of the Philippines against which Beijing has in recent months increased its maritime assaults. The underlying logic appears to be that, in a conflict scenario, China would conveniently pummel off its coast into readied allied crosshairs rather than attack from behind the U.S.’s westernmost defenses.

Even if that assessment were true, Beijing has also been laying the groundwork to be able to project power from elsewhere. In the Third Island Chain, for example, in Fiji, it has maintained a police and military presence since 2011. Despite earlier rumblings that these arrangements might be revisited, Fiji’s Prime Minister Sitiveni Rabuka in November reaffirmed his country’s commitment to Beijing’s “vision for global security” and encouraged CCP investment in Fiji’s port infrastructure.

Facts & figures

Recommitting to the Pacific islands

Intense debate has emerged – especially inside Australia and the U.S. – about how China has been able to advance as far and as fast as it has in the Pacific islands. In Australia, nearly every government in the postwar era has worked to prevent a hostile power from gaining a military presence in the South Pacific. Since the 1980s, the U.S. has maintained Compacts of Free Association with Palau, the Marshall Islands and Micronesia – collectively, the Freely Associated States (FAS). Beijing has steadily been working to expand its security reach in all three. In Micronesia, for example, it has built government facilities, roads and schools. It has also undertaken vast political warfare operations to access Micronesia’s critical communications and port infrastructure.

How, then, might the U.S. and its allies mitigate further fallout and prevent Beijing from fully securitizing the Pacific islands? The most immediate and apparent answer is for allied nations – the U.S. in particular – to signal their robust and long-term commitment to, in America’s case, the FAS, and the wider Pacific islands.

For the U.S. this means swift renewal and funding of the Compact of Free Association (COFA) agreements with the FAS. The COFA with Palau is due to expire on September 30, 2024. Yet those with Micronesia and the Marshall Islands were set to expire on September 30, 2023, and have been extended to February 2, 2024, as they await U.S. congressional approval. A short-term extension is better than nothing, but congressional dithering suggests a potential waning of U.S. commitment – a perception which, even if untrue, has only been exacerbated by the COFA’s exclusion from the 2024 National Defense Authorization Act, which is traditionally seen as ‘must-pass’ legislation.

Failure to renew the COFAs could eventually divest America of its exclusive military access to the FAS. U.S. privileges guaranteed under the agreements include the establishment of military facilities as well as the authority to conduct military exercises and station military personnel. The pacts also afford the U.S. strategic denial rights, meaning that foreign military forces and personnel can enter FAS territory only if explicitly authorized by the U.S. The U.S. could, then, for example, deny Chinese vessels access to FAS ports. In return, the FAS receive U.S. economic aid and are granted access to some U.S. federal programs. For the FAS, America also provides security and defense – most notably through the U.S. Coast Guard’s Fourteenth District fleet.

Should these provisions be rescinded, this would facilitate the likely presence of CCP police and PLA troops in the FAS, as well as Beijing’s probable purchase or construction of strategic port infrastructure. Sustained American commitment to the FAS is, then, the lowest-hanging fruit in parrying Chinese influence in the region.

Along with considerations about Chinese activities in the Pacific states, Pacific island leaders stress the importance of economic development, construction of needed infrastructure and climate change mitigation. These concerns have been outlined in the 2018 Boe Declaration on Regional Security which, having recognized “an increasingly complex regional security environment,” embraced an “expanded concept of security.”

The U.S. and allied nations will have to work with Pacific island nations to manage these challenges – bilaterally, collectively and routinely – if they wish to remain preferred regional partners. Among other measures, this includes increased maritime patrols and a more general shift from a posture of maritime domain awareness to maritime domain enforcement. In June, for example, Palau requested heightened U.S. patrols of its waters following several illicit incursions by Chinese vessels into its exclusive economic zone. The vessels were believed to have been surveying Palau’s underwater fiber optic cables. Elsewhere, off the coasts of Vanuatu and Tuvalu, for example, Chinese fleets fish illegally. Pacific island nations are generally aware of the illicit activities in their waters but cannot yet address them.

A commitment to the Pacific islands must also involve U.S. and allied efforts to counter CCP political warfare and buttress regional democracies. In Solomon Islands, Chinese slush funds appear to have succeeded in “postponing” the 2023 election and extending pro-CCP Prime Minister Sogavare’s term. If the election is further delayed, it would set a dangerous precedent for the region. Allied partners should, then, support anti-corruption and transparency initiatives, and fund independent media in the Pacific islands. Attention must also be paid to electoral integrity, particularly in the FAS. The FAS have large expatriate communities and little means of monitoring, for example, campaign spending among them. Beyond the Pacific islands, in the Maldives, the 2023 election of pro-CCP presidential candidate Mohamed Muizzu was facilitated in part by the Maldivian community in Sri Lanka, to which Beijing funneled funds to secure the votes needed for victory.

Scenarios

For Beijing, the Pacific islands are a core component of its Indo-Pacific strategy and wider aim to create a new world order. Should the U.S. and its partners fail to commit to the island nations and match the CCP’s growing influence with their own, this would likely pave the way for greater Chinese influence and even control in the region.

U.S. military access to the region, for example, could be severely constrained, if not denied. In August 2022, the U.S. Coast Guard cutter (USCGC) Oliver Henry was prevented from refueling in Solomon Islands. Last January, Vanuatu similarly failed to issue timely clearance for the USCGC Juniper to dock at its port to refuel. Both governments blamed domestic bureaucracies for the mishaps, yet the high-profile nature of the events and the subsequent failure to remedy them suggests CCP influence likely played a role. Should China continue to securitize the Pacific islands, such events could become more commonplace. In the event of military conflict over Taiwan, for example, the U.S. – including its forces in Guam – would then likely be stymied from any defensive measures.

Chinese dominance of the Pacific islands would also likely leave Australia and New Zealand isolated, with unpleasant implications for the national security of both nations and their allies. For Pacific island nations, CCP political and military influence would also undermine state sovereignty as the situation in Solomon Islands has shown.

Should the U.S. and its partners wish to mitigate against such a scenario, they will have to act quickly. As China has already made inroads, its complete ouster should not be the aim. Rather, in an alternative scenario, China could yet become a less strategic regional actor. Its police and military presence would be pared back, and future attempts to acquire critical port infrastructure denied.

Much of China’s activities would, then, be in sectors such as climate change mitigation and non-critical infrastructure, with regional security provided for by the U.S. and allied partners, including Australia and Japan. No doubt, Beijing would persist in its efforts to assume a heavyweight role in the region. Confronted by a strong bloc of nations, however, those efforts would amount to little. Achieving this goal would keep the Pacific islands from becoming yet another regional flashpoint.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.