Beijing’s motivation in China-Taliban relations

With the Taliban entrenched in power in Afghanistan, China is building up relations to prevent a security breakdown.

In a nutshell

- China is the most active foreign power in talks with the Taliban

- Beijing is primarily after security, not minerals or wealth

- Ensuring Kabul has total control over Afghan territory is Xi’s primary goal

Chinese diplomats have been meeting their Afghan counterparts almost weekly since the establishment of a Taliban government in Kabul. Analysts East and West are struggling to explain the emissaries’ visits; most allude to some sort of emerging “cooperation.” This term, however, explains little.

Cooperation is the action or process of working together to the same end. It is, however, highly doubtful whether the Chinese Communist Party and the Taliban share the same end. Even if, on an abstract level, both are pictured as wanting to assert their power, it is unclear what power each is showcasing. Engagement, focused on risk mitigation amid a potential security vacuum, is therefore Beijing’s most likely aim in such talks.

There is certainly no denying the flurry of diplomatic activity between China and Afghanistan in recent months. According to all available sources, Beijing has the most active representation in Kabul. China installed an ambassador there in September 2023, has invested in Afghanistan and has welcomed the country’s representatives to its international initiatives.

One way of understanding the terms on which China interacts with Afghanistan is to separate Beijing’s domestic goals from its international or geostrategic projection. Under current circumstances, Beijing sees domestic factors as the top priority.

The domestic view

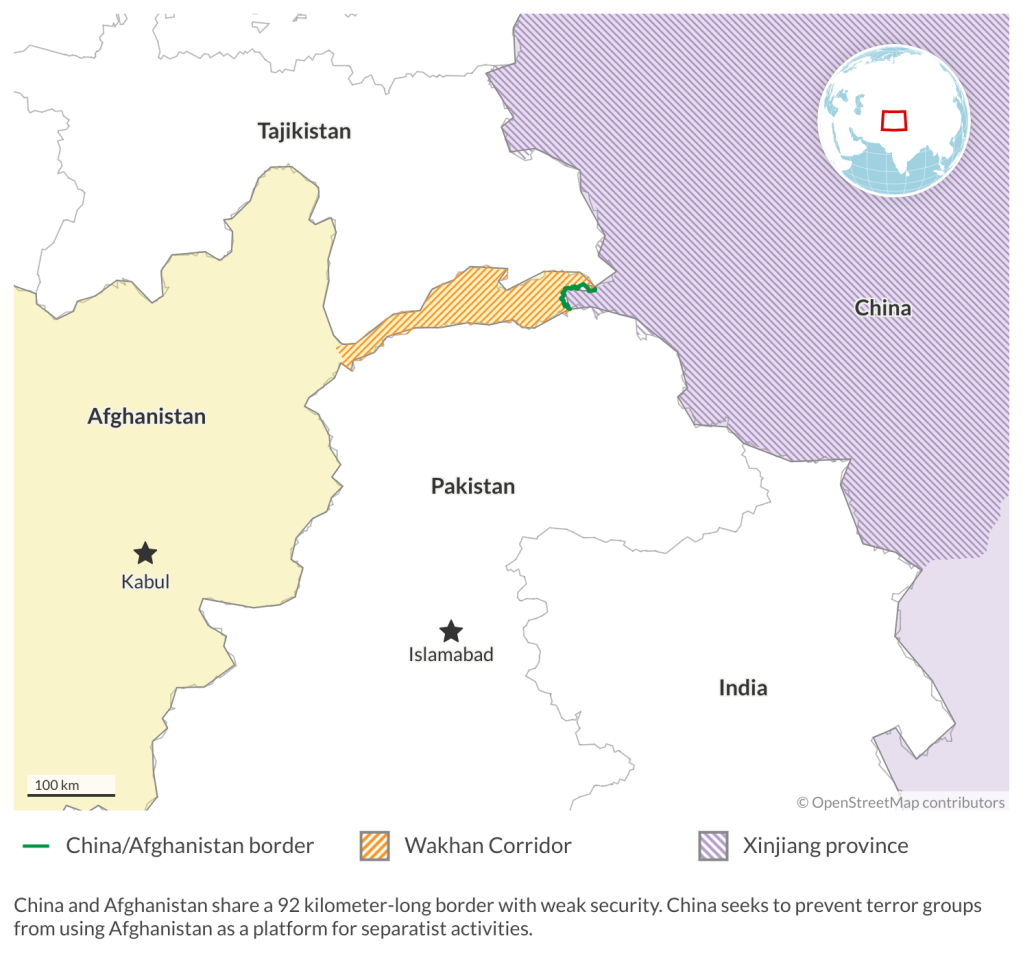

The communist party’s leadership focuses on order and security, and this applies to Afghanistan as the two countries share a 92 kilometer-long border. Since Taliban rule began, the northeastern part of the country encompassing the Wakhan Corridor – which borders China – has quickly destabilized. Sources report that terror groups are using Afghanistan as a platform. China fears a potential spillover of terror and separatist activities.

Therefore, Beijing’s engagement with Kabul is focusing on maintaining order and security. This should not be considered a sign of cooperation or friendship with the Taliban. It is instrumental for China to have a government in Kabul that is able to control the whole of Afghanistan, especially their shared border, and one that is willing to combat terror groups. Naturally, China also wants to protect its investments and citizens in Afghanistan, but this is a lesser concern.

China hypothesizes that a strong Taliban – however distasteful to Beijing – is the best way to ensure that more extremist and anti-Chinese groups do not gain a foothold. Additionally, China wants to have a single interlocutor that can establish order and, if necessary, be responsible in case of problems.

Read more on Afghanistan, South Asia and the Taliban

- Afghanistan’s sad story – and a new wave of immigration

- Scenarios for Afghanistan’s critical raw materials

- India’s stake in the Afghanistan conflict

The international view

It has been argued, especially by Western observers, that China is ready to invest in Afghanistan. The main reasons cited are the country’s strategic location and its wealth in natural resources including lithium, copper and rare earth elements. Indeed, some of Beijing’s envoys to the country have been speaking about such investment opportunities. Since 2023, tens of millions of dollars of Chinese investment have flowed into Afghanistan.

There is no doubt that China wants to project power over Central Asia. First, the region is a key, if not the core, component of the Belt and Road Initiative. Second, as a global power, China needs to project such posture, even if only for the sake of its version of the Monroe Doctrine: leave Asia to Asians. Third, on a regional level, China wants to keep competing powers at bay; primarily India, and, secondarily, Russia, both of which have some influence over Afghanistan.

In May 2023, Beijing and Islamabad agreed to expand the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) to include Afghanistan. This corridor provides a blueprint for civil-military cooperation aiming to enhance the participants’ connectivity.

Problems with the international view

However, all things considered, explaining China’s activities in Afghanistan in terms of projecting international power seems far-fetched. While it is true that CPEC has expanded to encompass Afghanistan, the Chinese also made it clear that counterterrorism is the only priority in the first years of working together.

Furthermore, Asian sources report that while China sees the potential of CPEC, it already considers it a risky endeavor. It is a source of exorbitant state debt for Pakistan, and China does not know whether it will be able to see returns on its investment. It is worth noting that CPEC attracts the ire of extremist groups, which could develop into a Chinese security problem.

Facts & figures

Regarding minerals and rare earths, China already has deposits of these elements at home. They are well integrated into Chinese supply chains, are cheaper to extract and fall under the auspices of the Chinese sovereign. None of these factors apply in Afghanistan. On the contrary, around 80 percent of its income has traditionally been foreign aid. Kabul is ill-prepared to trade globally. The Taliban expect aid from China, but not necessarily commerce.

On the regional level, it is a fact that India and Russia wield some soft power over Afghanistan. But India’s assertive policies are a source of doubt to the Taliban. China does not need to invest too much to counter its southern neighbor. While Moscow is more than happy to coordinate the Afghanistan issue with Beijing because the Kremlin also sees it primarily through the lens of security and counterterrorism.

Motivation for Xi

The activities of the Chinese Communist Party and the Chinese state are an extension of President Xi Jinping’s personal interests and his search for a legacy. Pivotal to this quest is ensuring the party’s continued power in maintaining order and security in Greater China. Those in the leadership ranks also share this goal as a means of gaining political power, including in a bid for President Xi’s favor and possible succession.

Having tied their public personae to order and security, Chinese leadership is more concerned about the domestic Chinese factors explained above than about projecting international power in Afghanistan. Additionally, taking the current state of China’s economy into consideration, since 2023, President Xi has been downplaying the importance of the BRI. It seems he does not want his legacy to be determined by the Silk Road alone. For his personal gain, order and security are more important. Following suit, a security arrangement with Afghanistan trumps economic interests.

Chinese leadership does not like the volatile political situation on its doorstep nor the potential for terror seeping into southwestern China. Moreover, investments in Afghanistan are a gamble. And so, China is unlikely to cooperate with the Taliban, at least not until the group establishes a reliable monopoly on power throughout Afghanistan. For the members of the Chinese politburo and state institutions, engagement with Kabul predicated on solidifying security can yield the highest payoff.

Scenarios

How does this analysis translate into scenarios for the near-term future?

Most likely: Engagement – not cooperation

The most probable scenario is that China will continue to engage with the Taliban, demanding they form a stable government that has the entire country under control, and that they suppress any Uighur groups while sealing off the border to China. In recompense, Beijing will consider providing some aid and pay geostrategic lip service to Kabul, nominally making commitments under CPEC and investing in prestigious but unimportant projects.

Possible but not likely: Aversion

This scenario is not very likely but is still more plausible than true cooperation. It sees Beijing reducing its engagement with the Taliban and perhaps looking for alternatives. These would most likely not involve attempts at instituting a new government, but rather deepening Afghanistan’s global isolation paired with a hermetical sealing of its relationships with China, Chinese institutions and regions. This scenario will materialize if the Taliban fail to assert themselves over their country and to monopolize power. This scenario will also become a reality if the Taliban are perceived as China’s enemies or as facilitating operations for any group deemed terrorists by China.

Least likely: Cooperation

Working together toward common goals is the least probable scenario. In it, China fully integrates Afghanistan into both CPEC and the BRI. Beijing makes important and expensive investments in developing Kabul’s military and civilian infrastructure. In exchange, Beijing is granted extensive rights for exploring natural resources, conducting operations to increase security and obtaining the usual commercial licenses.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.