Where have all the economists gone?

Support for free trade is nearly a consensus view among economic experts. Yet amid growing threats posed by deglobalization, economists are failing to stand in its defense.

In a nutshell

- The most developed countries have embraced elements of deglobalization

- Economic arguments for free trade are falling on deaf ears

- The global economy will likely close up further before the pendulum swings back

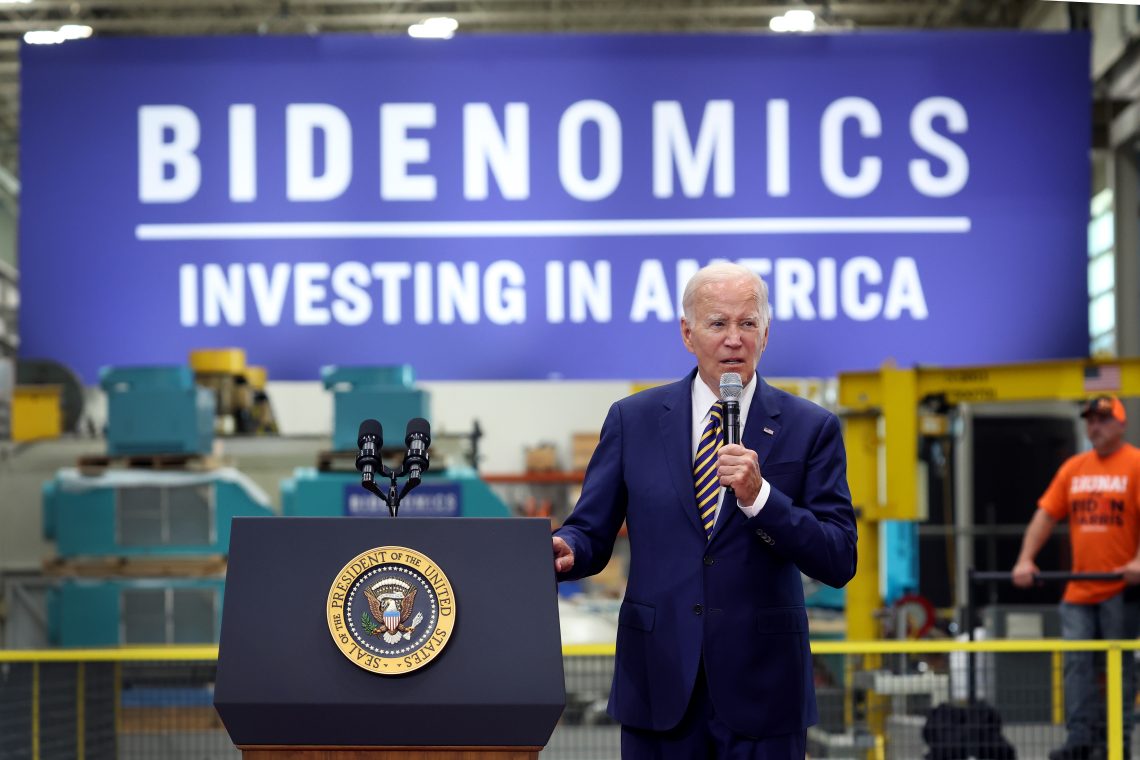

When the history of globalization is written someday, 2022 will be seen as a pivotal year. That August, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) was passed in the United States and enacted by President Joe Biden. Only slowly and belatedly did many economic observers recognize the law’s fundamental, long-term implications for the world.

It was not just the inaccurate, almost ironic title of the extensive legislation; it deals less with reducing inflation than with protectionism, tax incentives, support for domestic industries, price caps and subsidies, all wrapped up in the guise of fighting climate change. The IRA, in fact, is a historical milestone. At 272 pages, it effectively signals the end of the era of global openness that began quietly with Deng Xiaoping’s reforms in China and received a massive boost with the collapse of communism and the fall of the Iron Curtain.

These few golden decades brought about a profound development of the international division of labor, a massive enrichment of large parts of the world’s population and a great increase in international trade. Such a significant expansion and deepening of globalization is likely unparalleled in recorded history, surpassing in scope even the so-called Belle Epoque in Europe before the First World War. Despite this, advocates of the free market have been relatively quiet about the rising tide of deglobalization today.

Perhaps economists’ most widely held view is support for free trade based on the societal benefits of exchange within a competitive market.

The U.S. has long been a tireless supporter, driver and patron of global trade liberalization and less restrained capital flows. It has also been a fundamental guarantor of the rules-based system under the World Trade Organization (formerly the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade) – which is why the recent American turn to protectionism and localization is so significant. Just as some banks are systemically important to the financial world, some countries are systemically important to global trade. Foremost among them is the United States.

As it happens, in a development as ironic as the title of the IRA, today’s gradual closing-up of the U.S. is being led by some of the very same people who helped build the golden days of globalization. John Podesta – a lawyer who served as Bill Clinton’s chief of staff in the roaring 1990s, as a negotiator for many trade liberalization moves and then as an adviser to Barack Obama – is now leading the entire implementation of the IRA. As a senior and influential adviser to President Biden, he oversees the distribution of some hundreds of billion in “climate investment” set to be injected into the U.S. economy.

From globalization to etatism

If former champions of trade have abandoned the cause, how can the threat of deglobalization face any serious resistance – whether from politicians, bureaucrats or voters? An essential terrain will be the battlefield of ideas, with economic arguments playing a central role.

With some exaggeration, perhaps the only widely held view among economists is support for free trade based on the societal benefits of exchange within a competitive market. There are many intellectual disputes in economics about the allocation efficiency of markets, the role of the state and its interventions, the relationship between the primary factors of production and much else. However, an endorsement of free international trade has always been strong and broadly shared.

Now, this ideal is suddenly crumbling before our eyes – and yet it does not seem to be arousing widespread rebellion or outrage from the economic community.

Ever since the Covid-19 pandemic, which disrupted a number of formerly smooth mechanisms of logistics, production and trade, there have been serious concerns over how deeply globalization has become entrenched. The pandemic also intensified brewing geopolitical tensions between the U.S. and China.

Pressures for deglobalization have been building, with increased calls for supposed national independence, self-sufficiency, strategic autonomy, prioritizing national interests and building resilience to shocks abroad. The IRA, however, represents an institutionalization and codification of all these tendencies. Moreover, it comes from the U.S.; when the mountain climber at the top starts to turn back, surely many below him will follow as well. All the more so when, despite the polarized and fractured nature of American politics, the turn mentioned above has support across the political spectrum.

Facts & figures

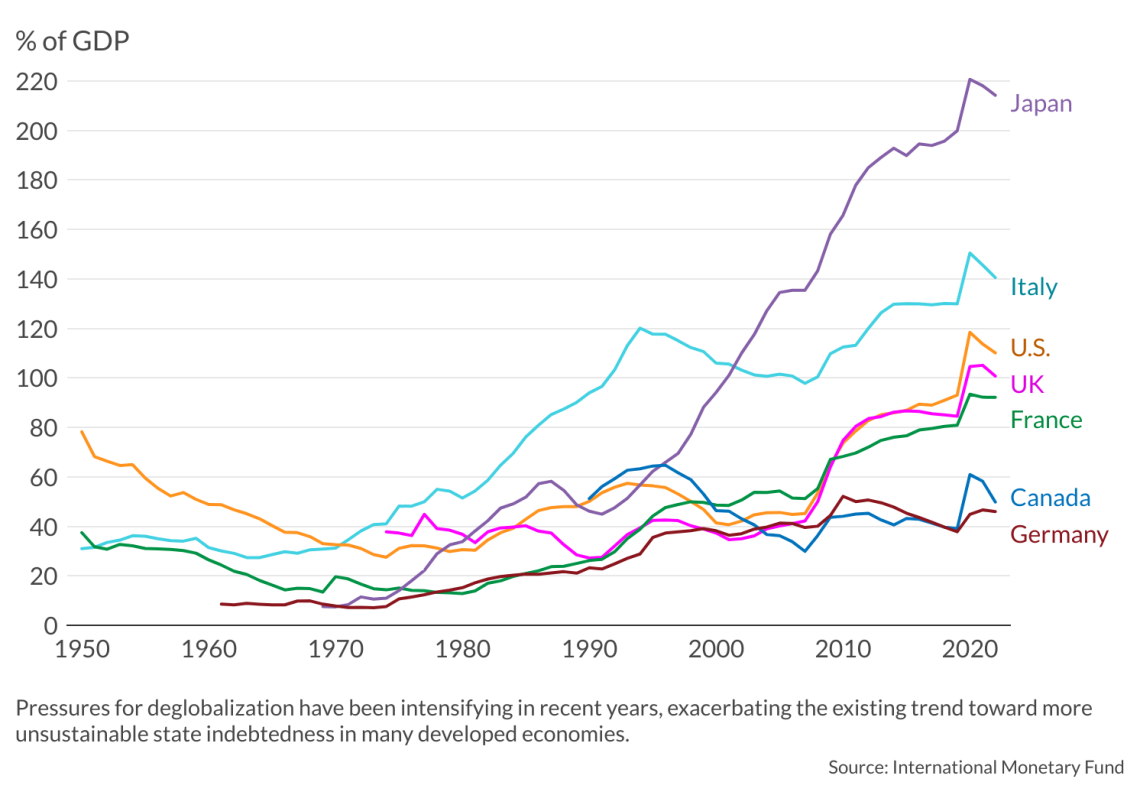

Taken together, this all means nothing short of a tendency toward the growth of the power and size of the state, more state intervention, more extensive public ownership, and more all-encompassing regulation – in other words, a tendency toward socialism, the restriction of markets and etatism. And it means greater and more unsustainable state indebtedness, a reality that is already evident in the developed world, especially in the U.S. To some extent, it is also a creeping return to the pre-1990 world; small steps, admittedly, but ones in the wrong direction.

It is happening everywhere, in different ways and settings. In Europe, there is a softening of fiscal rules. The prevailing voices are those who argue for cutting back on strict public aid rules, protecting national champions, renationalizing previously privatized businesses, and increasing the state’s ownership role in everything from chip production and weapons to medicines and housing development.

Strangely, this tack does not face many strong opponents. The world has experience with all of this, and much of it is still within living memory. Yet the intellectual resistance of the very profession that ought to know better – economists – is barely visible. Why?

The psychology behind deglobalization

It turns out that, throughout history, we economists have not been able to communicate or persuade with our knowledge in times of populism. In part, this is because, in many ways, economic truths are counterintuitive. Friedrich August von Hayek rightly described the job of economics as showing people how little they really know about the things they assume they can control and plan.

It goes against the intuition and common sense of the many who do not understand the power of spontaneous order. Such people believe that good or evil comes from a particular person, leader or politician who either decides everything badly or everything wisely and is responsible for the consequences. It is a natural worldview, embodied in fairy tales and James Bond films alike. People often prefer a “good” boss or leader to one constrained by rules.

Against this natural idea of good and bad rulers, economists have an uphill battle with their model of spontaneous organization. But it is one of the most potent economic ideas ever: that sometimes all you need are sensible rules and their enforcement and that a free society can organize itself with the help of the market, competition and price signals. The reason is that no one has enough information to run society effectively from a centralized position.

Read more by Mojmír Hampl

Squaring the circle of the EU’s fiscal rules

Welfare is the result of human action, not human design, as Ludwig von Mises might have put it. With each one in this system pursuing their own interest and seeking their own happiness, the goals of others are fulfilled through market forces.

No totalitarian ruler or politician can ever accept such a worldview – nor will any hardened socialist. Such a person, looking down on a city from a great height, would find it unbearable that cars drive themselves to and fro with no central planning, or without anyone telling them where to park.

It works because there are shared rules, plus individual, unorganized decisions by drivers about where to go. Managing traffic at the individual level of each vehicle would cause the system to collapse. Good traffic is the result of a fine balance between the spontaneous and the deliberate. And here, leadership is not to be confused with total or central planning.

The invisible hand

This is related to a second psychological fact: as humans, we can appreciate individual action much more than good rule-setting, regardless of how much it requires effort and intellectual capacity. A doctor saves a single life and is justly admired for it; good rules improve the lives of millions. The doctor does specific good, while the economists’ reasoning is abstract and general. Yet, it is social scientists and economists who can propose the systemic adjustments that make it possible to get richer and improve people’s standard of living on a large scale.

Unfortunately, if they’re successful and everyone gets richer on average, most take it for granted or as the result of their personal efforts – not well-designed rules that work for everyone. A rising tide lifting all boats eventually leads public discussion to focus on why some vessels are bigger than others. Similarly, if, on average, everybody is getting poorer, they typically fail to focus on the systemic errors at the root of the impoverishment. In truly totalitarian societies, they may not even have access to information about their impoverishment for some time, an experience for many residents in 20th-century communist states after the borders were closed.

In public opinion, the concrete discovery of penicillin by Alexander Fleming might be voted the most important innovation of all time. But has not Adam Smith’s abstract discovery of the market’s “invisible hand” – and the formulation by numerous social scientists of how markets can and should work – saved more lives? These brought about a non-caste society, the division of labor, the freedom to choose work and specialize in it, and the relaxation of rules for the allocation of capital that came with technological progress. Millions upon millions of people since the 19th century have been lifted out of arduous unpaid labor, intolerable hygiene and food and shelter shortages, which, in lethal combination, led to the endless misery of life for multitudes of people.

In times like today’s, economists would do well to remind the world of these arguments. This should be the role of the profession: to put the brakes on the wheels of deglobalization, to recall the power of the market against the recurring powerlessness of central planners, to sell the idea of spontaneous order against etatism and the all-pervasive overregulation of the economy. We know from historical experience that an argument that does not ring true at the right time may never ring at all. Economists should take heed and start acting; it is not five minutes to midnight, it is five minutes past.

Scenarios

More likely: Continued deglobalization

The first, more likely scenario assumes that the forces of deglobalization remain strong and their dominance in public debate continues globally for many years. The arguments of liberal economists, which helped create the existing world trade order, will be sidelined entirely, as they were briefly in the post-World War II period. The world economy will have to go through a period of decline – closing borders, erecting new barriers and strengthening the role of the state – before later returning to sound economic roots.

Less likely: The economists strike back

In a second, less likely scenario, the period of existential shock following the Covid-19 pandemic and the adoption of the IRA in the U.S. proves short-lived. The political scene will then start reversing the trends of deglobalization, and openness will gain new momentum, driven first by economic arguments followed by political ones. A new breed of politicians in the mold of Margaret Thatcher or Ronald Reagan will emerge and begin making their impact.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.