Is there a future for the EU’s banking union?

After the 2008-2012 financial crisis, an EU banking union was meant to make the eurozone more resilient. A decade later, this remains incomplete as transferring responsibility for banking policy from the national to supranational level has met strong resistance.

In a nutshell

- The “Banking Union” project was the EU’s answer to the banking and sovereign debt crises that threatened the common currency a decade ago

- Despite Brussels’ repeated attempts to implement a common banking regulatory and supervisory system, it still lacks a critical component

- Some member countries fear the European deposit insurance scheme could make them pay for other countries’ irresponsible domestic policies

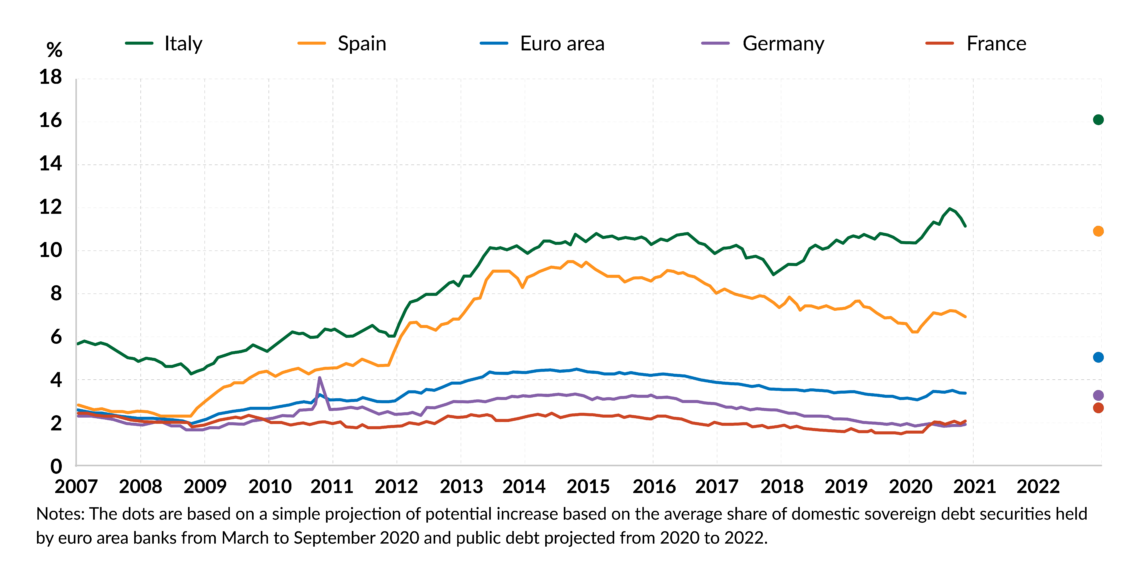

The euro crisis revealed several deep-rooted weaknesses of European banks. Oversized and undercapitalized, many continued to pose a systemic risk even after the 2008-2009 bailouts. Furthermore, the banks had developed an entrenched “home-bias” in their sovereign bond purchases. Some held an unreasonable percentage of their home government’s debt. These problems were found foremost in fiscally weak countries where governments’ creditworthiness was the lowest.

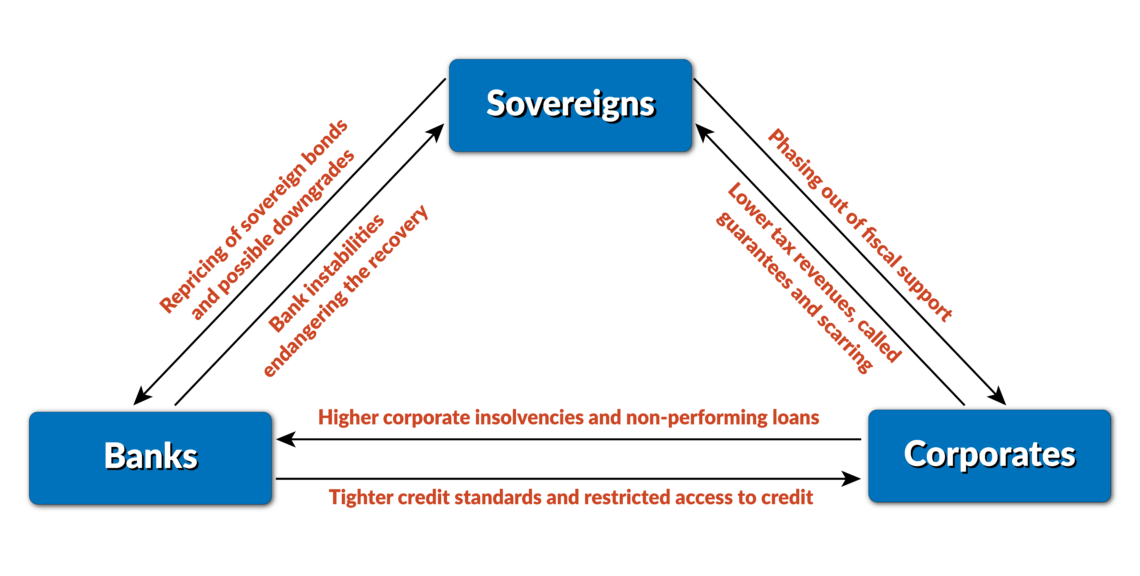

During the years 2009-2012, several euro area nations thus painfully experienced a range of downward spirals (so-called “bank-sovereign doom loops” or “double-drowning scenarios”), when debt-burdened governments and large troubled banks threatened to bring each other down. That could spell the end of the common currency, due to spillover or cascade effects.

At the time, in response to the urgency of a situation for which they were utterly unprepared, EU leaders promised the creation of a common regulatory and supervisory framework (a “Single Rulebook” in EU jargon) for the eurozone’s fragmented banking industry. The project was labeled the “Banking Union” (BU).

Fixing institutional flaws

Involving a transfer of responsibility for banking policy from the national to the supranational level, the BU should start by addressing the most acute threats to financial stability, such as the close links between public sector finances and the banking sector (i.e., the “sovereign-bank nexus”).

‘One money, one market’ without a joint fiscal authority, to be shared by several diverging and different-minded nations, was a risky experiment.

Ending the “too-big-to-fail” problem was the EU’s other great regulatory concern in those years. The idea was to make markets for banks “more transparent,” “unified” and “safer.” Ultimately, it was about restoring lost confidence in the banking system.

In hindsight, policymakers understood that the euro’s original design had set the stage for Europe’s severe multiyear sovereign debt crisis. As Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz saw it, the euro was “flawed at birth.” The choice to adopt a single currency “without providing for the institutions that would make it work” had proved to be a “fatal decision,” he wrote. “One money, one market” without a joint fiscal authority, to be shared by several diverging and different-minded nations, was an experiment doomed to fail, many experts think today.

In the aftermath of the 2012 debacle, when there still was intense speculation over the future of the common currency, a new institutional purpose was given high priority: achieving a “genuine” Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). This proposal was the subject of the much-cited Five Presidents Report, a document signed in 2015 by the then-presidents of the EU’s key institutions. Jean-Claude Juncker, Martin Schulz, Donald Tusk, Jeroen Dijsselbloem and Mario Draghi spoke for the European Commission, the European Parliament, the European Council, the Eurogroup and the European Central Bank (ECB), respectively.

The former bosses committed to a multistage “road map” for “deepening” the EMU along four fronts: Economic Union, Financial Union, Fiscal Union and Political Union. The BU, alongside the embryonic Capital Markets Union, was meant to become a keystone of the future Financial Union. The countdown to the Five’s ambitious plan started on July 1, 2015. It was supposed to be completed by 2025 at the latest.

Intangible concept

Ten years after the term “banking union” appeared in policy circles (reportedly, French economist Nicolas Veron was the first to use it in a 2011 research paper before EU officials picked it), it is time to ask how much progress has been made toward the attainment of the BU’s aims. How has the framework functioned so far? Has it lived up to expectations? These questions yield mixed answers in the specialized press as well as academic literature.

While EU technocrats generally praise the BU’s achievements in making the eurozone’s banking sector “safer” and “sounder,” some commentators are in doubt about whether the framework has even come into existence. For example, two researchers from the University of Luxembourg claimed the BU was “stillborn.” To this day, it remains a “far-off dream,” as a financial reporter put it. That the BU is an “unfinished project” might be the more accurate interpretation. As a matter of fact, two of its three founding pillars have been in place since early 2015.

In (or out of) place

One is the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM). It confers extensive micro- and macroprudential powers to the ECB. The latter has been mandated to directly supervise the eurozone’s systemically important banks (currently 114) and indirectly all the others.

Another motivation is to make sure that, in the future, taxpayers no longer will have to pay for costly bank bailouts.

The system proved effective. Supervised banks are generally far better capitalized today than they were 10 years ago. Also, the quality of their assets has improved significantly. According to Andrea Enria, chair of the ECB’s Supervisory Board, the total volume of non-performing loans (NPLs) in large eurozone banks was reduced almost by half between 2014 and 2019.

The BU’s second pillar, the Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM) – and its designated authority, the Single Resolution Board (SRB) – are supposed to come into play when the ECB determines that a bank is “failing” or “likely to fail.” The SRB’s mission is to ensure an “orderly resolution” of unviable banks to avoid some of the disastrous 2008-2012 scenarios repeating themselves (such as the risk that a failing bank pulls down others with it or, worse, that it triggers the bank-sovereign debt vicious circle).

Another motivation is to make sure that, in the future, taxpayers no longer will have to pay for costly bank bailouts. To finance resolution operations, the SRB will primarily mobilize the bail-in tools established in 2014 by the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD). If these are exhausted, it will call upon the Single Resolution Fund (SRF), an emergency fund financed by contributions from the banking sector. As of July 2021, the fund reached 2 billion euros. By the end of 2023, it should attain the target level of 1 percent of the value of covered deposits of all credit institutions operating within the BU.

As Mr. Veron argues, the SRB has known long delays and a difficult start. So far, it has taken only a handful of bank resolution decisions: three in 2017 (Banco Popular, Banca Popolare di Vicenza, Veneto Banca) and one in 2018 (ABLV). All four have been heavily criticized, and the SRB has been the target of dozens of lawsuits. These and other recent bank scandals (Greensill Capital or Wirecard, for example) also brought to the fore limits in the SSM’s oversight system.

Missing pillar

It is, however, the third, so far missing, pillar of the BU, the European Deposit Insurance Scheme (EDIS), that gives rise to most controversy. Its stated purpose is to provide “stronger” and “more uniform” depositor protection for the euro area. The idea is to prevent panic withdrawals (so-called “bank runs”) if a bank becomes unviable. EDIS should also allow for a better distribution of the costs of bank failures. It would reduce the losses endured by central banks in a failure scenario. Like the national Deposit Guarantee Schemes (DGSs) already in place, EDIS should apply to deposits below 100,000 euros of all banks in the Banking Union.

In 2015, the European Commission published the first legislative proposal for a eurozone-wide deposit insurance scheme, but it did not fall on fertile ground. Two years later, the Brussels eurocrats came up with a watered-down proposition of a “gradual” introduction of EDIS. In 2018, it was the turn of a “hybrid model,” in which EDIS would come into play only when national DGSs run out of money. No agreement could ever be reached. According to Euroactiv (a media network specializing in EU policies), a new Commission proposal could be on the table shortly.

Unwanted solidarity

From the start, Germany prevented negotiations from going forward. Ludger Schuknecht, a former chief economist of the German Federal Ministry of Finance, summed up his country’s concern: EDIS would mean that other countries would soon be liable for the consequences of misguided domestic policies, without those countries being able to influence such behavior.

Facts & figures

The biggest problem of eurozone-wide burden sharing is that it creates the wrong incentives. Once the common backstop is in place, both governments and banks could be tempted to increase risk-taking behavior, Mr. Schuknecht warned. Thus EDIS would “mean less, not more, stability in the countries of Europe, if the costs of domestic toxic legacy assets and of bank, supervisory and political mistakes can be dumped onto others,” he wrote. In June 2021, during a Eurogroup meeting, Germany’s finance minister Olaf Schulz emphasized, yet again, that as long as the shortcomings inherent to EDIS have not been properly addressed, no deal is in sight.

A key question is whether these days regulators are better equipped for future crises. For former member of the ECB’s Supervisory Board, the answer is no.

Currently, discussions are stuck to the point that the eurozone’s finance ministers could not even agree on a date to continue them. Insiders think that “serious talk” will not start before the German federal elections in September 2021 – or, more likely, the French presidential election in spring 2022.

Timed out

Ultimately, cynical observers may be proven right: EU leaders will commit to finishing the BU… one day. The time has long expired, others say. It is first and foremost a matter of credibility. Regardless of whether a banking union is even desirable, the fact that almost a decade after committing themselves to that common framework, the eurozone’s leaders remain unable to reach a consensus on how to complete it raises questions of capability and accountability.

A key question is whether these days regulators are better equipped for future crises. For former member of the ECB’s Supervisory Board Ignazio Angeloni, the answer is no. The coronavirus crisis has caught them “again partly unprepared,” he writes in a recent report.

Mr. Angeloni – who had been the chief coordinator in the preparations of the SSM in 2012-2013–regrets that the BU’s objectives are today more “elusive” than ever. If the goal was to make banks more efficient and profitable, it has not been attained. The European banking sector remains fragmented, overbanked and uncompetitive at the international level. The hoped-for risk-diversification and cross-border integration have not picked up either.

A banking reform “left at midway” entails “dangers,” Mr. Angeloni warns. Covid-19 could bring them to light. Many banks never fully recovered from the 2008 financial crisis. Now they find themselves amid a new storm. As the pandemic persists, even profitable and well-capitalized banks could face substantial credit losses and capital declines. According to the European Banking Authority, the quality of business and consumer credit will continue to deteriorate in the months to come. A “slight rise” in NPL volumes can already be observed.

Scenarios

For the moment, many of the banks’ weaknesses are masked by the gigantic public safety net put in place during the pandemic. Banks have greatly benefited from state guarantees, borrower assistance, massive liquidity support from national central banks and the ECB and, finally, a temporary loosening of some regulatory constraints, such as reduced capital requirements and greater flexibility in the treatment of NPLs.

However, as Mr. Angeloni rightly points out, once the relief and recovery programs are withdrawn (which is only a matter of time), the frailty inherent to the European banking sector “will come back to the fore, magnified.” The sovereign-bank nexus remains another critical issue. Over the past tumultuous year, it has become stronger, not weaker. To face economic fallouts, euro area governments have taken on historically high levels of debt. At the same time, banks in some eurozone countries have substantially increased their sovereign debt holdings.

The ECB’s Financial Stability Report of last November does not rule out that, in a not too distant future, Europe could be facing a new bank-sovereign doom loop. If the EU’s half-hearted banking reform has still not been finalized by then, the euro could quickly come under stress again, just as it did 10 years ago.