The dangers of preferential treatment for sovereign debt

Eurozone countries’ bonds are classified as “zero-risk,” meaning banks are not required to hold any capital against such assets. The system creates a perverse incentive for banks to stock up on sovereign debt. Putting risk assessments on government bonds could destabilize some countries’ economies.

In a nutshell

- Regulations classify eurozone countries’ debt as “zero risk”

- EU banks do not have to hold capital against such assets

- Lenders stock up on government bonds, risking overexposure

- Rating such debt could destabilize some economies

In December last year, Daniele Nouy stepped down from her post as chair of the supervisory board of the European Central Bank (ECB) and handed over the reins to Andrea Enria, former chair of the European Banking Authority (EBA). As her tenure came to an end, Ms. Nouy did not restrain her optimism. “We have delivered in making the European banking system much safer and sounder,” she told one newspaper.

European Union regulators agree that 10 years after the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression, the banking sector has become more robust and resilient. For example, the EBA’s latest EU-wide stress-test shows that banks’ solvency ratios have increased overall. The European Banking Federation points out that credit institutions have made considerable efforts to strengthen their balance sheets and rebuild solid capital positions.

Besides, banks have improved the quality of their assets. Under the guidance of the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM), they have worked hard to get rid of non-performing loans (NPLs). Those NPLs had cut into their profitability for years and thus held back their ability to lend effectively. As a result, the level of bad debt in Europe fell from a “scary” 1 trillion euros in 2014 to about 650 billion euros by the end of 2018, Ms. Nouy recalled. She emphasized the “good job” the particularly NPL-encumbered Italian banks have done in this respect.

There is a long way to go before balance sheets can be considered ‘fit and proper’.

Still, there is a long way to go before European and, all the more so, Italian banks’ balance sheets can be considered “fit and proper.” New vulnerabilities – the result of accrued political uncertainty, a revival of protectionist forces and persistent economic sluggishness in the eurozone – could hamper their ability to reduce legacy assets further.

More importantly, the specter of a new Italian debt crisis last year revived deep disagreements among regulators on basic economic understandings and policy responses. At the heart of the ongoing dispute is the privileged treatment of sovereign debt in the current EU prudential framework.

Safe-asset status

The problem can be traced back to the first Basel accords (Basel I, coming into force in 1992), which classified debt from governments in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) as zero-risk – in other words, as the safest imaginable asset a bank can hold. The assumption lives on through Basel II and III, as well as in the actual European Capital Requirements Regulation and Directives.

Before the 2008 financial crisis, the pretense that government debt carries a zero-risk weight was never really challenged, as sovereign default was considered highly unlikely in advanced economies. Many at the time thought that an individual country could not fail, arguing that monetary and fiscal policy could offer a range of ways out for a government facing the threat of insolvency.

The euro crisis proved them wrong. It made clear that sovereign debt is not immune from rescheduling (for instance, in 2015 Greece failed to make a loan repayment to the International Monetary Fund on time and had to apply for debt restructuring) or, worse, default.

No-bailout clauses

When it comes to sovereign debt exposure, the European Monetary Union (EMU) is designed to implement specific requirements. First, as ECB executive board member Benoit Coeure explains, the credit risk for euro area sovereign debt is real. European government bonds are a kind of “sub-sovereign” issue, insofar as the ECB and the 19 different fiscal authorities that constitute the eurozone cannot be “consolidated within a single ‘federal’ balance sheet.”

Moreover, the “no-bailout” clause of the EU Treaty explicitly prohibits “monetary financing” of member states through the ECB, encouraging governments to keep up fiscal sustainability. The idea behind the EMU is that markets should remain the judges of the soundness of sovereigns’ fiscal policies and, ultimately, their creditworthiness.

Conversely, the EU’s bank recovery and resolution directive (BRRD), adopted in 2014, forbids governments to bail out failing domestic banks so that they are not dragged down into dangerous debt-spirals.

Home bias

Deliberately or not, the Basel-based regulatory framework encourages banks to stock up on sovereign bonds. Since no capital must be set against them, they can hold these assets in unlimited amounts.

This presents a problem: large lenders could end up having exposures that exceed the amount of capital they hold. Their ability to absorb losses would be overwhelmed in a sovereign default crisis. Today, two major Italian banks, UniCredit and Intesa Sanpaolo, could find themselves in such a situation.

Also, most of the government bonds piled up in Italian banks are Italian. There is some 387 billion euros of domestic sovereign debt stored in Italian banks, equivalent to 10 percent of their total assets.

The naturally strong link between a sovereign and domestic banks can become explosive in times of crisis.

Economists have a name for banks’ preference for their own governments’ debt-securities: “home bias.” The naturally strong link between a sovereign and domestic banks can become explosive in times of crisis, as it reinforces a “vicious feedback cycle” between them, as described by one team of researchers: “Fear about the solvency of a nation’s government fans fears about the solvency of the nation’s banks, which in turn weakens the economy, thus worsening the sustainability outlook for the nation.”

The German Council of Economic Experts identifies further causes for the problematic interdependence between lenders and sovereign-credit risk: banks’ low equity ratios, on one side, and countries’ high debt-to-GDP ratios on the other. In Italy’s case, the latter figure amounts to 133 percent – all while its economic growth hit zero in the fourth quarter of 2018 and its debt climbs toward a vertiginous 2.6 trillion euros.

Governments’ poor credit ratings also play an important role in the acceleration of the “double-drowning” process. During the sovereign debt crises of 2009-2012, the eurozone painfully experienced “how quickly trust in the sustainability of public debt can form and transform and, with it, the perception of creditworthiness,” recalls Mr. Coeure. In the blink of an eye, bonds labeled 100-percent safe became too risky for investors to hold.

Dangerous embrace

Last summer, after the election of a euroskeptic, populist government in Italy, the fears of a “doom loop” between a vulnerable country and its closely connected (and no less weak) banking system arose anew. Throughout 2018, Italian debt was hit by several waves of massive sell-offs, as investors dreaded that, at one point, Italian state debt might not be paid back again.

Under such menaces – exacerbated by the repeated downgrading of government debt by powerful external credit-rating agencies – concerned bond prices usually fall and yields rise; domestic banks owning large stockpiles are particularly hit. They may be forced to reprice their holdings, raise capital to absorb losses and reduce their lending activity, all of which undermines the faltering economic health and financial stability of their home country even further.

Facts & figures

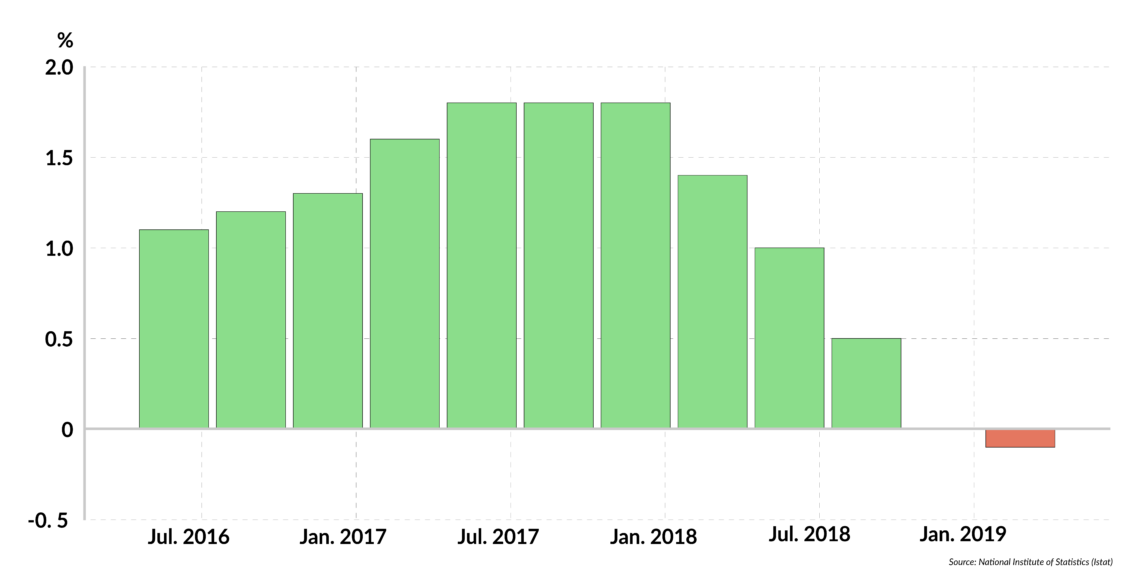

Italy: Stunted growth

Italy's annual GDP growth rate, by quarter

When, on top of this, the government in question threatens to defy the EU spending rules by wildly increasing public spending, as did Italian Deputy Prime Minister Matteo Salvini in October 2018, the circle comes back around. Back in 2011, The Economist described this perilous bank-sovereign nexus, as “a dangerous embrace.” The characterization still holds today.

In December, Italy was able to avoid EU sanctions after reaching a last-minute compromise with Brussels over its 2019 budget. However, Mr. Salvini’s most recent plan to squander billions more euros in the 2020 budget recently triggered a penalty procedure by the European Commission that could lead to a multibillion-euro fine, once again sapping the country’s economic strength.

Continent-wide contagion

“Italy is one small shock away from a sovereign default of global scale,” is how The Telegraph interprets the latest IMF Fiscal Monitor.

History has shown that banks’ high sovereign debt exposure does not only impair financial stability in their home country. It can also spill over to the banking systems and government finances of other EU member states.

If a sharp sell-off of Italian debt were to start again, French banks would be the first outside Italy to be affected, as they hold huge stocks of Italian public and private debt (over 280 billion euros in late 2018, according to the Bank of International Settlements).

France could be on the hot seat anyway, not least because, as Economy Minister Bruno Le Maire has pointed out, the Italian and French economies are tightly interwoven. Also, for months, the Yellow Vest protests have shaken France. To ease tensions, French President Emmanuel Macron recently announced new public spending measures and tax cuts that could, like in the Italian case, stretch the budget deficit beyond the EU limits.

A French doom loop could follow Italy’s, dragging down other eurozone countries.

Weakened banks, a government under pressure, investors’ trust unraveling: a French doom loop could follow Italy’s, dragging down other eurozone countries.

Regulatory headache

Several international regulators are calling for an end to European sovereign debt’s safe-asset status. At the forefront is Ms. Nouy, who is urging legislators to “ditch the zero-risk-weighting assumption,” and force banks to build up the missing capital cushion for government bonds. Banks should be made aware of the risks they take when they hold sovereign bonds of “less secure countries,” she said.

Even the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS), the origin of the controversial exemption, set up in 2015 a high-level Task Force on Sovereign Exposure, inviting experts to consider potential reforms for closing this ill-advised “regulatory gap” (as former Bundesbank executive board member Andreas Dombret calls it). Two years later, a discussion paper was issued, in which the BCBS acknowledged the utmost importance of reconsidering the preferential treatment of sovereign exposures. Unfortunately, no consensus could be reached.

The European Commission was left to decide. It promptly passed the ball on to Europe’s courts, recommending that policymakers do not take any action for the moment, as altering the treatment of public debt could distress the (seemingly not so “safe and sound” after all) European banking sector.

Political confrontation

Changing the safe-asset status of euro area sovereign debt is highly unpopular in (mostly southern) deficit nations, whose bonds would be poorly rated by supervisors. “Penalizing” sovereign bond holdings (as two Spanish authors describe policy changes favoring the inclusion of government debt in the risk-weight calculation) could backfire, it is argued. domestic banks would indeed see their capital requirements rise significantly, which would impact their financial health and, consequently, the economy at large.

Also, the stabilizing role domestic banks can play during sovereign crises would be lost. As shown by an IMF study, when sovereign default looms, bond yields rise, and (notably large) banks tend to increase their exposure to the concerned government’s debt. By doing so, they eventually prevent the government in question from drowning.

In 2015, a fiscal union was high up on the agenda. Today it looks like wishful thinking.

Understandably, Germany’s position is at the opposite end of the spectrum. Its sovereign bonds are reputedly the safest in the eurozone. Weakening the bank-sovereign nexus is key to financial stability in Europe, the Bundesbank insists. If European authorities continue to bury their heads in the sand, Germany might even refuse to adhere to the European Deposit Insurance Scheme, a central pillar of the future Banking Union.

So, Europe’s solidarity is not as solid as many hoped. The EU is even further from a fiscal union that would allow member states and the ECB to tackle economic and financial shocks in unison, and eliminate, once and for all, the term “sovereign default” from the bloc’s vocabulary. In 2015, a full-fledged fiscal union was high up on the agenda. Today it looks like wishful thinking.

Breaking the nexus

Meanwhile, regulators face two burning questions. First, how should sovereign risk be rated? Answering that is a challenging task, as was evident in discussions among ECB supervisors during a colloquium last December. “One should still do it,” retorts Ms. Nouy’s closest collaborator, Sabine Lautenschlaeger; the least the ECB should do is introduce a “concentration-risk measure.”

Ms. Nouy’s successor has a similar vision. At the helm of the SSM, Mr. Enria might recommend solutions he considered in a theoretical paper a few years ago. These include “regulatory incentives to diversify sovereign risk” and a progressive “reliance on mark-to-market valuations of sovereign exposures.” Although sovereign risk would not be entirely discarded, its impact might be mitigated.

The second question is whether it is true that the ECB’s cheap-loan policy fuels banks’ home bias. The ECB’s various measures of quantitative easing, such as those providing financial compensation to banks for losses incurred by their lending at close-to-zero interest rates (so-called long-term refinancing operations, or LTROs), are often accused of contributing to the rise of domestic debt in banks’ balance sheets. Indeed, banks are inclined to use the generous ECB subsidy to load up on domestic sovereign debt (for which there is no capital counterpart required) instead of granting new loans to the private sector (for which there is). A new wave of such “targeted longer-term refinancing operations” (TLTRO III) is due for September 2019, with Italian and Spanish banks being the primary beneficiaries.

Thanks to ECB stimulus, domestic banks constantly have new liquidity at their disposal. As long as indebted states can siphon money from them, the dreaded bank-sovereign nexus will continue to be a “noose around Europe’s neck.”