Is more less? The challenges facing EU enlargement

The prospect of Ukraine and other countries joining the European Union presents security, fiscal and political risks to the bloc’s cohesion.

In a nutshell

- Current EU candidates vary on economic and governance standards

- Brussels must balance geostrategic imperatives against internal politics

- Fundamental reforms to the EU would pave the way for new members

On July 23, 2022, the European Union declared Ukraine and Moldova to be candidate members, bringing the number of such states to seven, alongside Turkey (1999), North Macedonia (2006), Montenegro (2010), Serbia (2012) and Albania (2014). Bosnia and Herzegovina became the most recent addition, in December 2022.

In November 2023, the European Commission submitted its progress report on these candidate states, while France and Germany jointly published a report with recommendations for EU reform from the perspective of enlargement. The EU agreed on December 14 to official open accession talks with Ukraine, while the Commission has also recommended negotiations with Moldova and granting Georgia candidate status.

The EU, having lost one of its economically strongest and militarily most powerful members, the United Kingdom, is committed to including eight new members – all of which have economies far below the EU average, large development needs, weak armed forces and deep cultural and social differences. Some of them are directly threatened by a nuclear superpower. Brussels is facing the prospect of some 35 members by around 2040 or, alternatively, a serious setback in the event of stalled candidacies.

Georgia and Kosovo have submitted applications. While the latter is unrecognized by five current EU members, the former will present the question of where the bloc’s borders lie. In 1987, Morocco’s application was rejected on the grounds that it was not part of Europe. The same could be said of Georgia.

Four European states have refused EU membership: Norway, Switzerland, Iceland and the UK. Should any of these have second thoughts, they are bound to be welcomed with open arms. In the long run, the EU could have between 33 and 39 members.

In pursuing enlargement, the EU will face five core challenges:

- Timing: speed vs. credibility

- Security: national prerogatives vs. the geopolitical and financial imperatives to pool resources

- Finances: heterogeneity vs. unity of purpose and the functioning of institutions

- Decision-making: diversity of interests vs. the ability to act decisively and coherently

- Popular support: preserving the union vs. dwindling support from citizens

Timing

With Ukraine’s existence threatened, timing is crucial. EU membership presupposes that Ukraine remains an independent, pro-Western state. A defeat for Kyiv would be a setback for the EU. Negotiations about accession cannot be dragged out as long as they have been with Turkey. The candidate could cease to exist before it can become a member.

The EU emphasizes that accession is a merit-based process. At the same time it underlines that Ukraine’s membership is a geopolitical and strategic imperative. In the end, it will have to weigh these interests against objective progress on reforms made by Ukraine. The EU is faced with a divide between its geopolitical ambitions and its limited ability to change facts on the ground.

Preparing for membership takes time; it took Sweden and Finland two years, and Spain and Portugal, emerging from dictatorships, eight. The process for Ukraine, formerly part of the totalitarian Soviet Union and with few traditions in democratic institutions and the rule of law, is likely to take even longer. Implementing the necessary reforms is difficult enough in peacetime; it is almost impossible during war.

Most EU member states have strongly euroskeptic political parties that seem to be gathering strength after a temporary loss of appeal in the wake of Brexit.

For previous enlargements, the EU could drag negotiations on for as long as it seemed necessary. In the case of Ukraine, the time frame is constrained by a hostile power with every interest to derail the negotiations. Time and circumstances now demand quick results, even if the fine print still has to be thrashed out. The worst outcome would be if all the proud proclamations are exposed as hollow verbiage and accession gets bogged down in technical minutiae – portraying an EU that is strong in words, weak in deeds.

Can Ukraine meet the Copenhagen criteria by 2030? What if it can’t – and if the war with Russia drags on for years? Membership for Ukraine, Turkey and Serbia is not only a question of these countries complying with the required criteria; geopolitical and security interests dominate.

The EU is facing a dilemma. If it insists on full compliance with the acquis communautaire before membership, the bloc may miss a unique historical opportunity. Yet if it turns a blind eye to serious deficiencies, it risks taking on unresolved and possibly insoluble problems.

Security and foreign policy

Whatever the shape of a future EU, it will have to accord higher priority to security aspects. In the case of Ukraine, EU membership is inconceivable without prior NATO membership, since the bloc has no capabilities itself for guaranteeing Ukraine’s defense. But how firmly could an enlarged EU count on the unwavering support of the United States?

In Washington, there is growing impatience with an EU that takes a free ride on security. The U.S. is running up public debt at an increasing pace – $33 trillion today, a $2 trillion annual increase in 2023 alone (close to 150 percent of gross domestic product, comparable to Italy). It stumbles along from one near-budget default to another, with its legislature dysfunctional and its constitutional stability threatened. Should Donald Trump return to the White House in 2025, the country’s reliability and very democratic credentials could be permanently damaged.

How long can 27-plus European countries – no poorer or less populous than the U.S. – expect Americans to risk their own blood and treasure for “far away countries of which they know nothing,” simply because they are unable and unwilling to provide for their own security? As the U.S. pivots toward the Pacific, the North Atlantic is losing its position as an undisputed priority.

Past EU attempts to equip itself with credible military means have had little success. The EU Rapid Reaction Force never materialized. Battle Groups were declared operational in 2005, but have not once been committed. The much-vaunted Headline Goal has remained a paper exercise, like the two Security Strategies of 2003 and 2016.

Great hopes were pinned on the Permanent Structured Cooperation concept. But the most ambitious projects between Germany and France (FACS, MGCS) are stumbling along. Whether and when they will ever produce operational weapon systems remains uncertain. Experiences with the joint transport aircraft A-400 M are hardly encouraging: after a 13-year delay, its performance remains disappointing, its reliability questioned and its interoperability limited.

Crises in Ukraine and the Middle East have demonstrated the importance of drones, air defenses, reliable intelligence and active combat personnel on the ground. The EU lacks elementary capabilities in all these dimensions. Future defense of the EU only makes sense if it is embedded in a defense of Europe as a geopolitical unit. That requires the active participation of Norway, the UK and possibly Turkey.

The Common Foreign and Security Policy has made little progress since the European Council of Cologne in 1999. The EU does not speak with one voice on most major international questions. Its members can hardly find a common line vis-a-vis China, they have fallen apart over the Middle East and there are obvious divergencies in attitudes toward Russia, Serbia and Turkey. Without strong leadership and strategic purpose, the EU will not achieve strategic autonomy.

Finances

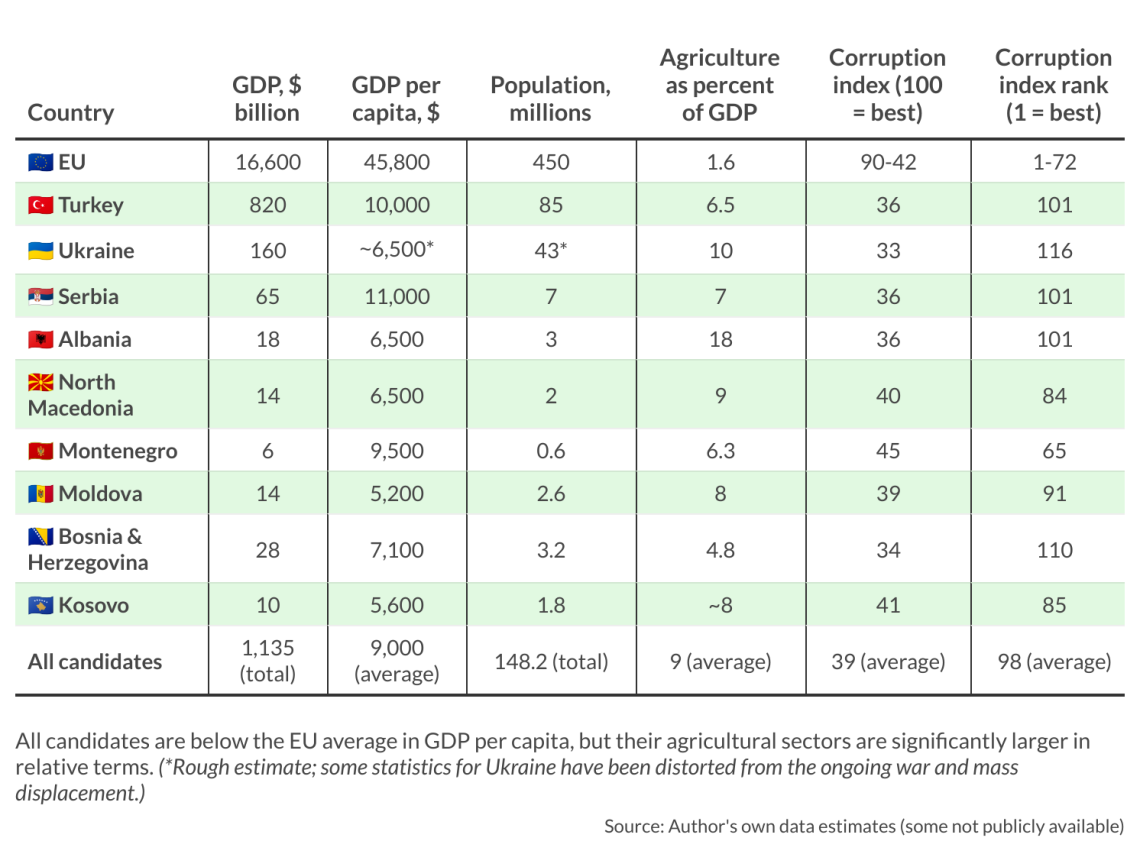

At present, the EU spends about 40 percent of its regular financial resources on cohesion and regional development, another 40 percent on agriculture and less than 1 percent on security and defense. All candidates are far below the EU average in gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, but significantly above in the size of their agricultural sectors.

Apart from the economic disparities, there are worrisome divergences in the rule of law. The Transprency International Corruption Index (100 is very clean, 0 highly corrupt) for present EU members varies between 90 (Denmark) and 42 (Hungary). All candidate countries except Montenegro are below the lowest of this figure – behind states like Botswana (60) and Ghana (43) and more in league with Cote d’Ivoire (37) and Kazakhstan (36).

Even the lowest GDP per capita inside the EU, in Bulgaria, is double the figure of the most advanced candidate country. The economic output of Ukraine and Moldova is about a quarter of Bulgaria’s. Brussels is committed to financially supporting members below the EU average. All candidates would therefore qualify for massive transfers, leaving the bloc with three equally unpalatable solutions: increasing contributions from present members (many of whom would turn from net beneficiaries to contributors); withdrawing support from present beneficiaries (Poland and Hungary); or revising the thresholds or volume of the programs. Under current conditions, Ukraine could be entitled to about 20 percent of the total EU budget.

Facts & figures

While Montenegro or Moldova are small countries (together less than 4 million people), Ukraine has a large population of more than 35 million, on par with Spain or Poland. It has an outsized agricultural sector, supplying 12 percent of global wheat, over 30 percent of global oilseeds and significant shares of corn, barley, vegetables and fruit – all within structures that still reflect the consequences of Stalin’s collectivization. Private property in agricultural lands was only fully restored in 2020. Experts calculate that Ukraine could easily increase its agricultural production fourfold, provided that conditions of peace return and modern cultivation methods are adopted.

Under such circumstances, Ukraine could elbow out EU members that currently profit most from the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). If Poland and Hungary block grain and lorries from Ukraine in times of war, how will they react once Ukraine enjoys all the benefits of the CAP and free movement? Not to mention the position of France, the main beneficiary of CAP for the past 60 years. The policy would have to be fundamentally recalibrated.

The EU summit has opened the road to membership negotiations, but it had to resort to a procedural trick. The road ahead is going to be bumpy, full of potholes and with some rickety bridges across deep and wide gorges. It is a journey nobody has been looking forward to. Without Russia’s aggression, there would hardly be any serious talk about EU membership for Ukraine. The EU wants to accept a war-ravaged country that it considered hardly qualified for membership before the war. If U.S. support for Ukraine wanes, the EU should know that the burden of keeping Ukraine going will fall on its shoulders.

Decision-making

If all eight candidates were to join (an admittedly inconceivable prospect for Turkey under the regime of Recep Tayyip Erdogan), the EU population would increase from its present 450 million to somewhere between 500 and 590 million. The thresholds for decisions taken by Qualified Majority Voting (QMV) today are 55 percent of members representing 65 percent of the EU’s total population. With 35 members, that threshold would be 20 states representing 325 million people (or, with Turkey, 385 million).

Fiscally restrained EU members still hold a tenuous blocking minority, even if the departure of the UK weakened their position. In a body of more than 30 members, net recipients and countries that flaunt the fiscal stability criteria would hold a structural majority. The three large members of Germany, France and Italy could then exercise a veto only by acting in unison. Enlargement will probably also widen existing fissures among existing member states, since they would be very differently affected by Ukraine’s accession; German and Polish industries would likely profit from cheap labor and favorable investment opportunities, while French, Polish and Hungarian agriculture would face serious competition.

Read more by Rudolf G. Adam

Prospects for a multipolar world order

The EU will either have to shelve plans to widen the scope of QMV, or it will have to revise the thresholds if net contributors want to avoid being at the mercy of net recipients.

A commission of 35 commissioners would be impracticable, meaning that the traditional rule of one country, one commissioner would have to be reconsidered. But that would see some member states losing direct access to the most important decision-making body inside the EU.

Popular support

For the moment, solidarity with Ukraine in Europe is running high. Each enlargement of the EU has proved beneficial to all its members, even if to different degrees. It now seems that a quick admission of the current candidates will put an enormous burden on EU resources. Would taxpayers in EU states be prepared to accept huge transfers to new member states if their own economies are faltering? Will support for Kyiv’s defense against Russia continue once the costs of Ukraine’s accession to the EU are felt by European citizens? Some members are likely to face a multidimensional dilemma – between rising expenditures for defense, adaptation to climate change, social challenges and support for new EU members on the one hand, and a weakening economic and fiscal base on the other.

Most EU member states have strongly euroskeptic political parties that seem to be gathering strength after a temporary loss of appeal in the wake of Brexit. In Germany, the AfD seems destined to become the second strongest party (polls today give it more than 20 percent of the vote, ahead of the SPD, Greens and FDP). One of the party’s ideologues recently proclaimed that “this EU has to die for the real Europe to live!” The next presidential elections in France, in 2027, will be a test of strength for the National Rally party of Marine Le Pen, who has come in second in the last two votes. As President Emmanuel Macron will not be eligible for a third term, she will present a familiar and appealing face for many voters, particularly if social tensions grow.

In Sweden, Finland and even in the Netherlands, criticism of the EU is widespread. In April 2016, the Dutch electorate voted down an association treaty with Ukraine (61 percent against, 38 percent in favor, with a 32 percent turnout). In the end, the Dutch Parliament ratified the Treaty after the government explained it would not imply any military or financial help for Ukraine; five years later, these words had been overtaken by events. The recent electoral triumph of Geert Wilders is a bleak omen.

Scenarios

All these challenges leave the EU with a threefold dilemma.

It could meet the deadline and accept Ukraine (and a few other members) by 2030 after agreeing to a treaty revision, fundamentally revising its financial and agricultural policies and accepting incomplete reforms in some candidates. This option presupposes that NATO membership comes simultaneously with or precedes EU enlargement. Considering the problems that Sweden’s NATO membership has encountered, this scenario looks unlikely. It might be the best option for the body, but its probability is not more than 20 percent.

The second, less positive outcome would be a repeat of the case of Turkey. Accession talks would start only to get entangled in a plethora of sticking points. The deadline would pass, and the opposition of some EU members against Ukraine’s admission would prove adamant. Ukraine would receive “privileged association” but not full membership. At the moment, this seems the most probable outcome, around 60 percent.

The worst outcome, with some 20 percent likelihood or more, would be a Ukrainian membership forced by geopolitical events upon reluctant governments and even more reluctant publics. The deadline would be met, but most reforms inside Ukraine and the EU would remain unfinished (or papered over by talk). Kyiv could cause serious relocations by soaking up the lion’s share of the EU budget and creating new migratory pressures. Some existing EU members would feel poorer, not richer, after enlargement. This could fan smoldering anti-EU resentment and lead to electoral victories for euroskeptic parties, which would seek to leave the EU or at least trim its competencies. The EU would choke by gobbling too much too fast.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.