The EU’s new, more practical strategy for Africa

The new EU-strategy for Africa focuses on areas that are of crucial importance in the eyes of African governments: green transition and energy access, digital transformation, sustainable growth and jobs, peace and governance, and migration and mobility.

In a nutshell

- The EU’s strategy reflects Africa’s new geopolitical standing

- Investment will be favored over development aid

- Brussels could find it difficult to offer African countries the partnership they need

The European Union recently announced a plan to renew the Africa-EU Partnership, due to be discussed and officially adopted in October 2020 during the EU-African Union (AU) Summit. The strategy seems in line with former European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker’s promise to establish a partnership between equals through a radically different approach.

However, the next EU-AU strategy will have to adapt to a new global context. The COVID-19 outbreak has paralyzed European countries, the African partners are facing considerable uncertainty about how the pandemic will affect them, and China seems to be – at least for now – the only global player capable of assisting those in need.

Changing actors

Brussels’ new road map reflects the specific circumstances of African and European countries. It contains precise goals aiming to satisfy the most pressing needs of all players involved. According to the plan, relations between the two sides should focus on five areas: green transition and energy access; digital transformation; sustainable growth and jobs; peace and governance, and migration and mobility.

The new strategy reflects the substantial change in power balance that took place between 2007 and 2020.

This approach reflects the cumulative consequences of past strategies, including the 2000 Cotonou Agreement and the 2007 Joint Africa-EU Strategy. It also takes into account significant shifts that occurred on the African continent, such as the 2012 African Peace and Security Architecture initiative, the intensification of relations with other global powers (both established and emergent) and the launch of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA).

Furthermore, the new strategy also takes into account the substantial change in power balance that took place between 2007 and 2020. Because of the political effects of the 2009 debt crisis, the 2016 migrant crisis and Brexit, the EU became a less cohesive and more fragile actor, struggling to affirm its position on a global stage where its main asset – soft power – seems increasingly irrelevant. Meanwhile, Africa has raised its geopolitical profile through ambitious supranational structures, freer trade, more economic integration and calls for more self-sufficiency.

The return of realpolitik

Unsurprisingly, given the recent polarization and increasing competition for power, the new joint EU-Africa plan adopts a down-to-earth approach to foreign policy. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has called for a more strategic, assertive and united EU. In turn, High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Josep Borrell has repeatedly stressed the need for the EU to develop an “appetite for power” and increase its capacity for action.

On the security front, Brussels has acknowledged the relevance of hard power to ensure stability both in the African continent and in the EU. In economic terms, the proposed strategy focuses on tangible results. Development aid seems to give way to investment, with the private sector expected to assume a vital role. An increasing number of African countries are trying to move away from aid dependency, and access to energy and job creation remain urgently needed. Meanwhile, several sectors have grown thanks to digital leapfrogging. The priorities established by the EU are expected to be in line with those of Africa.

Facts & figures

Divergences and limitations

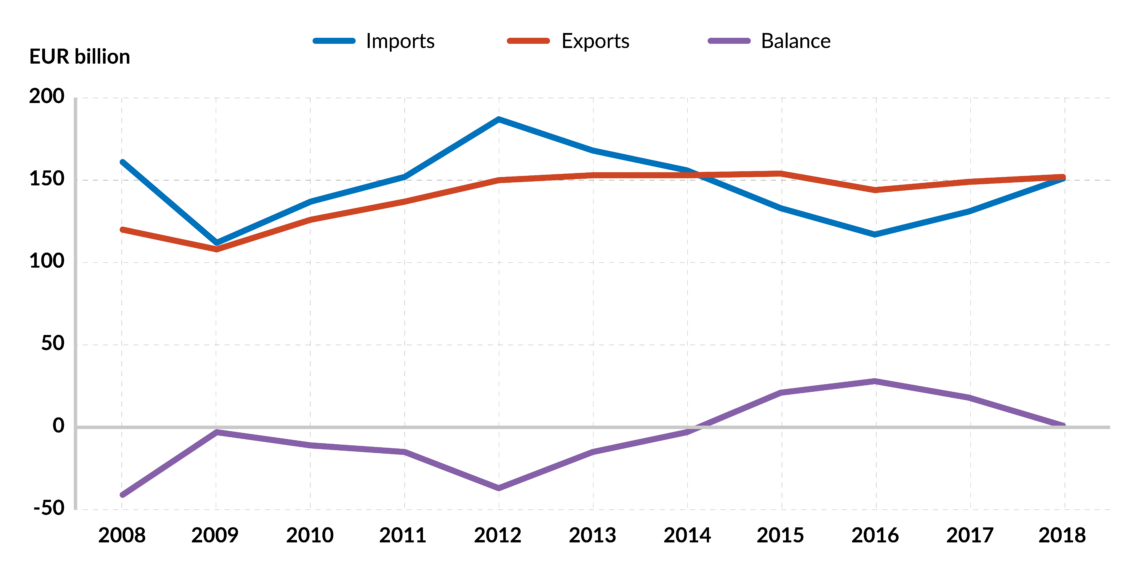

Unlike China, India or the Gulf countries, in its relations with Africa the EU has maintained, with few exceptions, a series of political and moral conditionals. Such impositions will meet increasing resistance, as the EU’s soft power is under challenge. At the same time, the AU is increasingly committed to the motto of “African solutions for African problems.” While the EU remains Africa’s leading donor and most important trading partner for both exports and imports, these flows will likely diminish as a result of the coronavirus pandemic. And so will Europe’s sway on the continent.

Migration has become a sore point between Brussels and African countries.

Over the past years, migration has also become a sore point between Brussels and African countries and finding win-win solutions has proven particularly challenging. The EU’s migration policy – including the 2015 European Agenda on Migration and the 2017 Malta Declaration – was designed against a backdrop of urgency and polarization. It is also based on fragile partnerships, as reflected in recent events along the Greek-Turkish land border.

However, remittances from abroad remain a crucial source of income for millions of Africans. For some economies, such as Somalia and Zimbabwe, they represent a financial lifeline. But whereas migration push factors are expected to remain high in Africa – higher incomes in Europe, increasing global mobility and persistent insecurity and humanitarian crises – the EU’s capacity to receive and integrate refugees and migrants will inevitably decrease. These trends suggest that Brussels will find it hard to offer African countries the kind of partnerships they want and need.

Scenarios

The implementation of the new EU-Africa strategy will depend on the leverage that EU and African participants bring to the negotiation table and, secondly, on how the current coronavirus pandemic will affect both continents in months to come. With this in mind, two scenarios should be considered.

1) Europe turns inward

Under this first and more likely scenario, massive challenges – including the economic and political consequences of the pandemic – will weaken the EU’s internal cohesion and, consequently, its capacity to engage with foreign players. In the short and medium-term, aid and trade flows to Africa will significantly decrease, further eroding Brussel’s position on the continent. At the same time, African countries struggling to contain the pandemic will turn to China, Russia or the Gulf countries.

This scenario would compromise the renegotiation of important engagement tools such as the Cotonou Partnership Agreement, which is due to expire this year. Whereas other competitors like the U.S. and the UK would likely face the same constraints, players such as China, Russia or the Gulf countries would be in a better position to offer African countries the kind of cooperation they seek.

2) Progressive stabilization

Under this second, less likely scenario, once the COVID-19 infection is past its peak, Europe will regain a surer footing. Whereas European economies – and the EU itself – would be deeply affected by the pandemic, this would not prevent Brussels from constructively engaging with Africa as a critical part of its strategy to build its power on the global stage. This scenario also presupposes that most African countries would not be severely affected by the pandemic. Under these circumstances, the new EU-Africa relationship would be based on an almost equal partnership (with a more fragile EU meeting a more assertive AU), therefore conducive to practical approaches focused on investment, digital transformation and job creation.