European gas crunch: Calm before the storm

The European gas crisis has begun to ease, and prices have fallen slightly after Russia made more supplies available. But there are many unpredictable factors at play, foremost among them political tensions between Russia and Europe, as well as rising Covid-19 infections.

In a nutshell

- Gas prices remain high but could begin to adjust

- Russia will provide additional supplies

- Many factors could push prices up or down

Europe continues to battle high gas prices, though the panic that swept the continent in October eased in November. There is a well-known saying in commodity markets: the cure for high prices is high prices. This helps explain recent trends. High prices are gradually attracting additional supplies, while customers look for cheaper alternatives, including coal in power generation – regardless of climate change concerns. Over time, the longer high prices persist, the stronger the signal will be for more investment in gas production and other infrastructure. Of course, the most unpredictable factor remains the weather.

The crisis has shed light on the significant influence Russia still has on the European gas market, despite the European Union’s deliberate attempts to weaken its sway over the years. Russia is still the biggest exporter of natural gas to Europe. The crisis, however, has brought competing sources of supply on the continent, a trend that will intensify in the coming years. In gas markets, much more than in oil markets, political and commercial interests are closely intertwined.

Gazprom supplies

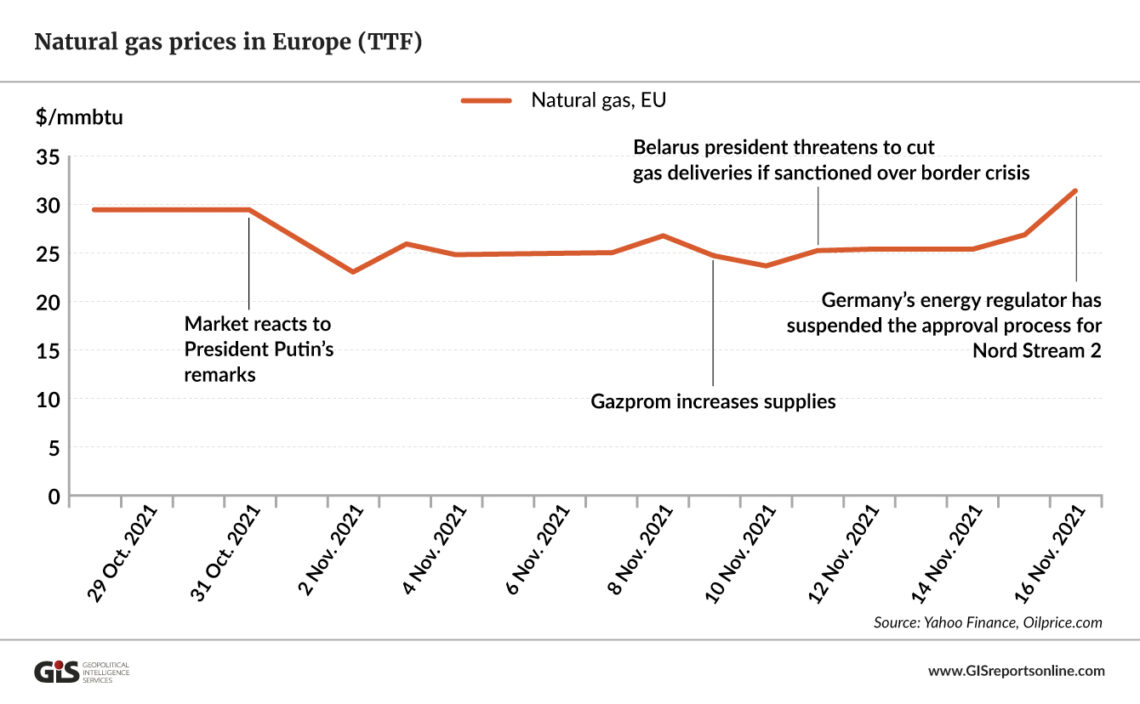

On October 27, Russian President Vladimir Putin stated that Gazprom, Russia’s gas giant and largest gas supplier to Europe, would start refilling underground storage facilities in the continent after domestic storage tanks are replenished. The announcement eased some of the pressure on European gas prices. Gas storage plays an important role in gas markets because it is used as a buffer at times of high demand (mainly for heating) and potentially tight supply. Low gas storage makes the market more nervous.

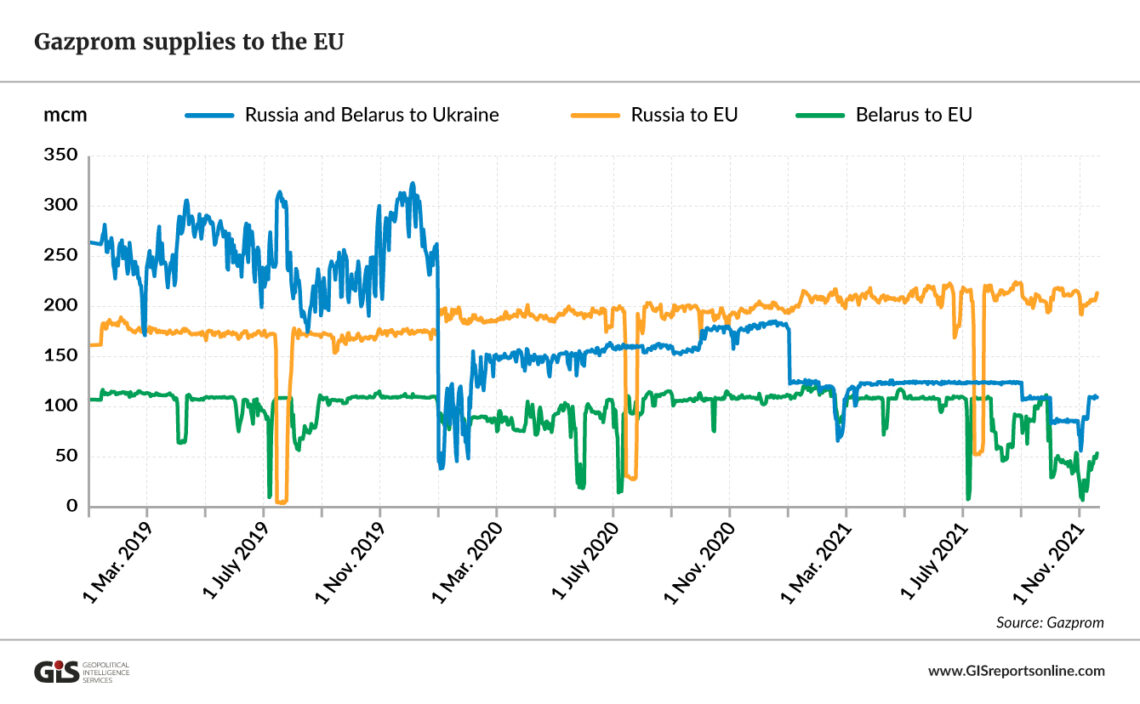

Prices further declined when the additional gas started to flow from Russia. It is reported that by mid-November, gas coming from Ukraine nearly doubled and from Belarus, through the Yamal-Europe pipeline, increased fivefold.

If Turk Stream 3 and 4 are built as well, Ukraine’s transit business will vanish.

Just as things were beginning to go smoothly, on November 11, Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko threatened to cut the transit of gas through the Yamal pipeline if the EU imposed sanctions over the migrant crisis on the Polish border. The following day, however, Russia announced its supplies would not be interrupted.

A week later, on November 16, Germany’s Federal Network Agency suspended the Nord Stream 2 pipeline authorization process, saying the operating company could not be considered an independent transmission operator, one of the legal requirements. The decision was surprising, especially in the middle of a crisis. Predictably, prices jumped. They eased shortly after the announcement, but they remain high by historical standards.

Transit headache

The suspension of Nord Stream 2’s approval process can be interpreted as no more than a typical instance of German red tape. But given its timing, it could also be seen as the EU toughening its stance on Russia – particularly with the latter’s perceived role in the Poland-Belarus migrant crisis. On November 15, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson gave a speech siding with the United States and urging the EU to stop Nord Stream 2. “We hope that our friends may recognize that a choice is shortly coming – between mainlining ever more Russian hydrocarbons in giant new pipelines, and sticking up for Ukraine and championing the cause of peace and stability,” he said.

Nord Stream 2 would allow Russia to achieve its long-coveted aim of bypassing Ukraine, the largest gas transit country in the world. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Moscow has been gradually reducing its reliance on Ukraine to export Russian gas to its most lucrative market – Europe. In 1991, 95 percent of its gas exports to Europe were shipped via Ukraine; today, it is 42 percent. Russia has built a web of pipelines to diversify its gas export routes, starting with the Yamal pipeline to Poland and Germany via Belarus in the 1990s; then Blue Stream under the Black Sea to Turkey, and Nord Stream 1 under the Baltic Sea to Germany. With the completion of Nord Stream 2, Ukraine’s role in transporting Russian gas would be reduced to 13 percent of Russia’s exports to Europe. If Turk Stream 3 and 4 are built as well, supplying gas to Southern Europe via Turkey, Ukraine’s transit business will vanish.

The new pipeline will allow the Kremlin to contest Ukraine’s transit fee policy.

Bypassing Ukraine presents challenges not only for Ukraine but for Europe and other Western allies, at least in the short term. The Ukrainian economy is still precarious. Transit revenues averaged 3 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) over the last 10 years – a substantial source of revenue to a government strapped for cash. The loss of transit revenue will also affect other transit countries including Poland, Slovakia, and to a lesser extent the Czech Republic.

Furthermore, the EU would be more exposed to Russia as it would not only rely on a single country for the lion’s share of its gas imports but also on Nord Stream as a single transport route. Nord Stream 2 is a replica of Nord Stream 1; it follows exactly the same pathway under the Baltic Sea and lands in the same location in Germany. Both projects have the same import capacity of 55 bcm per year each, 110 bcm per year combined. If Nord Stream 2 becomes fully operational, around 110 bcm out of 170 bcm of Russian gas deliveries to Europe (65 percent of total deliveries from Russia) will travel a single transport corridor.

Commercial ground

While these arguments have been debated since the inception of Nord Stream in the early 2000s, the economic drivers of changing gas routes from Russia, and the political issues this shift creates, have not been sufficiently discussed. What is less known is that Russia’s actions are justifiable from an economic point of view.

Gazprom sees two main advantages to the Nord Stream route. First, it lowers direct costs. As Gazprom’s key gas production base moves from the Nadym-Pur-Taz region to the Yamal Peninsula, the Nord Stream route is the most direct export route. Its total distance from the field to the delivery point in Europe is half as long as the Ukrainian route. Second, it lowers opportunity costs. The new pipeline will allow the Kremlin to contest Ukraine’s transit fee policy and prevent Kiev from using gas as a bargaining chip in negotiations with Gazprom or its clients in Europe.

Replacing the expensive Ukrainian transport route with Nord Stream 2 would therefore make Russian gas even more competitive relative to LNG imports in general – and to LNG imports from the U.S. in particular. Nord Stream will give Gazprom an extra edge in terms of cost competitiveness, which will also translate into improved margins in Europe and allow the company to crowd out American LNG if deemed desirable (on economic or on political grounds). Washington is concerned by the project; European gas markets are among the most profitable for U.S. suppliers.

Facts & figures

Expectations

The German regulator’s announcement surprised the market but did not cause mayhem. The decision may have been perceived as symbolic, making it a question of time before the certification is finalized (shareholders have around four months to rectify the problem). Nord Stream 1 initially caused a notable share of political friction between EU member states and Russia and Ukraine, but in the end, it went ahead.

Meanwhile, high prices in Europe have attracted additional supplies. Norway, the second-largest gas exporter to Europe after Russia, significantly boosted its pipeline gas exports to the continent in October. Norwegian gas is mainly market-based, unlike most Russian, North African or Middle Eastern gas, which is sold under long-term contracts linked to oil prices. In October, the Norwegian state-owned Equinor reported its greatest quarterly result in nine years, benefiting from higher oil and especially higher gas prices.

Europe can only hope for a mild winter.

Additional supplies could reach the European market relatively swiftly, notably LNG from the U.S. This type of gas is traded on the spot market and is not contracted, giving it the flexibility needed to respond to higher prices. The risk for Europe is the price signal in other markets, particularly Asia. A cold winter in Asia could capture U.S. cargoes otherwise destined to Europe, as they did in winter 2020.

But customers, be it in Asia or Europe, are also looking for practical alternatives. Coal usage is on the rise, not only in coal-rich Asia but also in Europe. So is fuel oil, albeit to a lesser extent since in Europe oil products are less commonly used than coal in power generation.

Interdependence

Perhaps the most reassuring aspect of the current situation is that Russia needs European markets as much as, or even more than, Europe needs Russian gas. Dependence cuts both ways: 38 percent of European pipeline gas is imported from Russia, but those exports to Europe constitute 85 percent of all Russian pipeline gas trade. The continent remains a key market for natural gas because of its overall level of consumption but even more so as a center for competition among different sources of supply.

Russia has blamed the crisis on market-based pricing, which the EU has been advocating for years. While it is true that such a mechanism is not risk-free, it does bring a flexibility that other pricing mechanisms, primarily Russia’s favorite long-term oil- indexed contracts, do not have. After all, markets work and clear relatively quickly when they are allowed to do so.

In the more immediate term, two additional forces are at work in Europe, and both could tilt the market in either direction. First, there is the rise in Covid-19 infections and the reinstatement of lockdowns and mobility restrictions. Should these translate into slower economic activity, gas demand will ease. Second, there is the weather, and Europe can only hope for a mild winter. Perhaps this is what the Germans are betting on.