Some inconvenient truths about the energy transition

Fossil fuels, particularly natural gas, should be integrated into the transition to a cleaner energy future. Otherwise, the ambitious targets promoted in the richer world – such as “net-zero by 2050” – will only be virtue signaling.

In a nutshell

- The energy sector holds the key to mitigating climate change

- Retaining gas in the energy mix would help the transition

- Reaching net-zero by 2050 requires bringing Asia onboard

The Covid-19 crisis has not diminished the momentum of ambitious climate and energy targets and policies; if anything, this pursuit continues to grow as more governments are determined to “build back better.” New tougher pledges are announced to minimize greenhouse gases (GHG) emissions, the culprit behind the warming of the climate, with carbon dioxide (CO2) contributing the lion’s share.

Energy roadmap

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), the energy sector, which is the source of around three-quarters of GHG today, holds the key to responding to addressing the global climate challenge. In its flagship “Net Zero by 2050” report published in May 2021 the agency gives several recommendations to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. Although still a work in progress, the net-zero concept refers to the amount of GHG added into the atmosphere being no more than the amount taken away.

One of the IEA’s bold recommendations involves halting the approval of new oil and gas fields for development, beyond projects already committed as of 2021. It is a stark departure from the earlier investment gap fears expressed by the agency: until recently it warned of tight oil and gas markets and high prices if investment in the pandemic-battered sector does not recover.

Absent technological breakthroughs, tilting the balance in favor of green energy will take a while.

The problem, however, is that most recommendations are easier made than implemented. Even the IEA acknowledges that a “huge amount of work is needed to turn today’s impressive ambitions into reality.” No wonder that, despite all the pledges, global CO2 emissions continue to rise. The substantial and persistent contribution of fossil fuels (that is, coal, oil and natural gas) to global primary energy mix and electricity generation over at least the last three decades suggests that absent technological breakthroughs, tilting the balance in favor of green energy will take a while. Another inconvenient truth is that, like it or not, for decarbonization to progress, fossil fuels, particularly natural gas, should be integrated into the transition to a cleaner future. Otherwise, the ambitious climate targets, particularly in the richer world, will simply be virtue signaling.

The science

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the United Nations body responsible for assessing the science related to climate change, argues that GHG emissions from human activity have increased rapidly since the preindustrial era, driven mainly by economic expansion and population growth. Global warming is likely to reach 1.5 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels between 2030 and 2052 if emissions continue to increase at the current rate, with disastrous environmental, social and economic effects. To avoid this scenario, GHG should be reduced significantly. In particular, the IPCC recommends that countries worldwide aim to reach and sustain net-zero CO2, if the world is to halt global warming in decades ahead.

Facts & figures

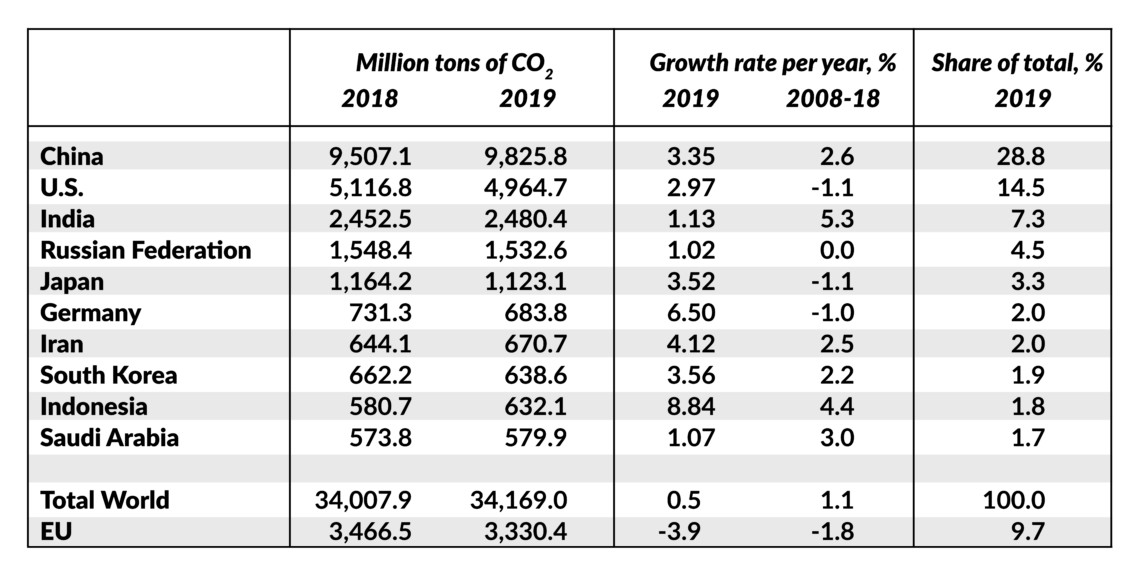

Since CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion and industrial processes are responsible for about 78 percent of the total GHG emissions increase from 1970 to 2010, according to the IPCC, lowering them will entail reducing demand for fossil fuels.

Stubborn mix

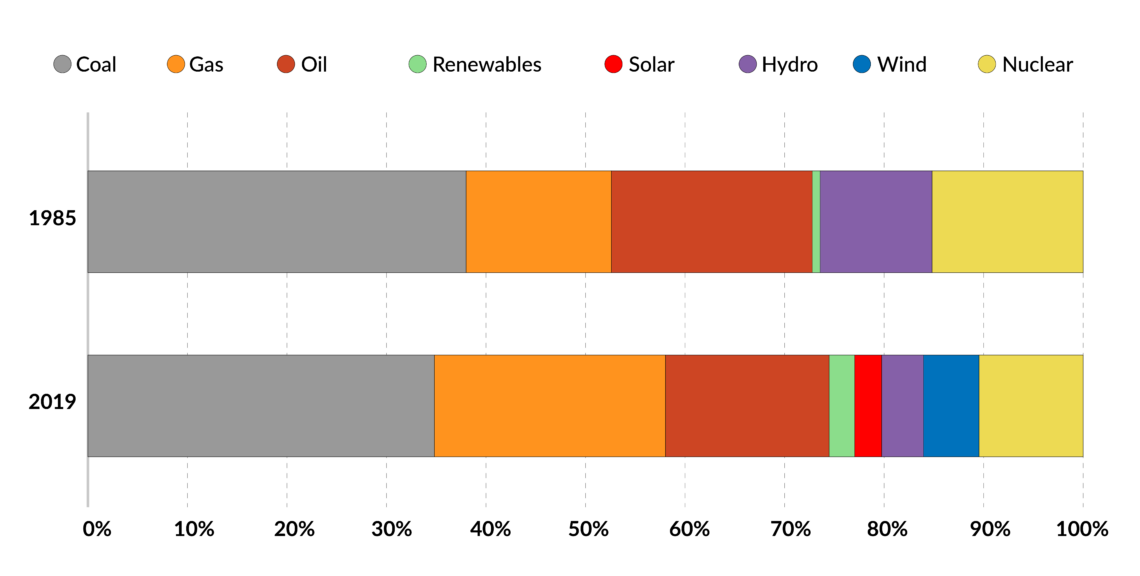

The plain truth, however, is that global energy consumption remains based on fossil fuels. In 2019, all modern renewables combined (wind, solar, geothermal and biofuels) accounted for five percent of primary energy consumption. In contrast, fossil fuels – coal, oil and natural gas – provided more than 84 percent. (The rest came from hydro and nuclear power with shares of around six percent and four percent, respectively.)

Facts & figures

More significantly, if we look at the electricity sector, an application where all fuels compete, the share of fossil fuels has hardly changed since 1985. Back then, it was just under 64 percent; 35 years later, it was 63 percent. The rapid growth in renewable energy seems to have come at the expense of other green energy, with both hydro and, particularly, nuclear power losing share. Clearly, the world still has a long way to go to fulfill the climate agenda.

Reading between the lines

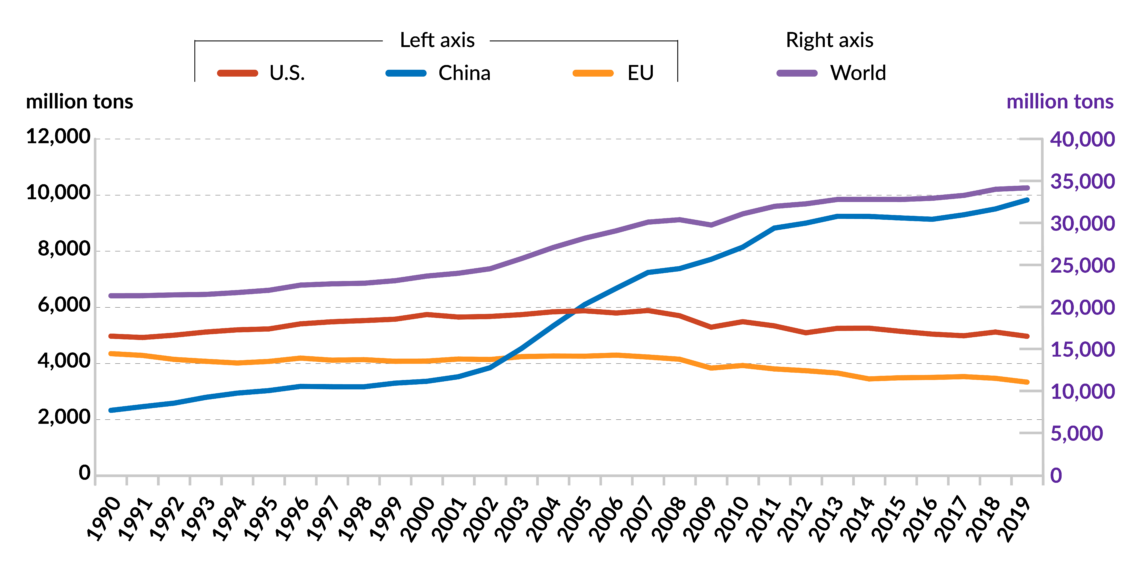

It does not take much to realize that to curb global emissions growth requires Asia, especially China, the world’s largest CO2 emitter, to be fully on board.

In September 2020, China’s President Xi Jinping pledged that his country, the world’s largest emitter of CO2, would aim to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060 while its GHG emissions would peak before 2030. In December 2020, President Xi also declared to the UN that China would reduce the carbon intensity of its economy (i.e., carbon emissions per unit of GDP) by 65 percent from 2005 levels.

Facts & figures

- According to the IPCC, human activities are estimated to have caused approximately 1.0 degrees Celsius of global warming above preindustrial levels, with a likely range of 0.8 degrees Celsius to 1.2 degrees Celsius. Global warming is likely to reach 1.5 degrees Celsius between 2030 and 2052 if it continues to increase at the current rate.

- In 2008, gas constituted 26% of U.S. primary energy supply, but by 2019 the share of gas had increased to 32%. In contrast, coal supply decreased from 25% to 12% (more than half) over the same period.

- The Chinese economy is predominantly fueled by coal, which provides 58% of its primary energy supply; by comparison, gas provides less than 8%.

- Around 13% of the world population does not have access to electricity; sub-Saharan countries in Africa have the lowest energy access rates in the world.

- More than eight out of 10 people in the in the world are expected to live in Asia or Africa by 2100.

Sources: IPCC, Our World in Data

This appears to be good news. However, while these pledges may seem ambitious, the fact that China’s carbon emissions reduction target is promised in such measurements means that Beijing will retain some flexibility. Many advanced economies have committed to a reduction of carbon emissions in absolute terms, e.g., tons of CO2 relative to a particular benchmark year. Choosing a relative carbon intensity target could also mean, especially in the case of China, that GDP growth is expected to decelerate; in such a case, carbon emissions would not be reduced as much as the numbers suggest.

The project aims to price carbon, thereby increasing the cost of carbon-emitting fuels.

The Chinese declare that they want to pursue the “right” balance between energy security (and self-sufficiency), economic development and the environment. But “right” is in the eyes of the beholder. China still favors economic growth and energy security over climate concerns because, despite the size of the economy, its per capita income is considerably below that of the United States and the European Union. Also, its economy is much more dependent on industrial production, with higher energy intensity than the service-based economies of the EU or the U.S.

Multispeed

Europe is at the forefront of combating climate change, aiming to be a climate-neutral economy with net-zero GHG emissions by 2050. To achieve its ambition, the EU is relying on a combination of aggressive policies. It supports the rollout of renewables to accelerate the transition to a greener energy mix. Also, it uses market mechanisms, primarily the carbon trading scheme or what is known as the European Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS). The project aims to price carbon, thereby increasing the cost of carbon-emitting fuels and improving the competitiveness of green energy.

Facts & figures

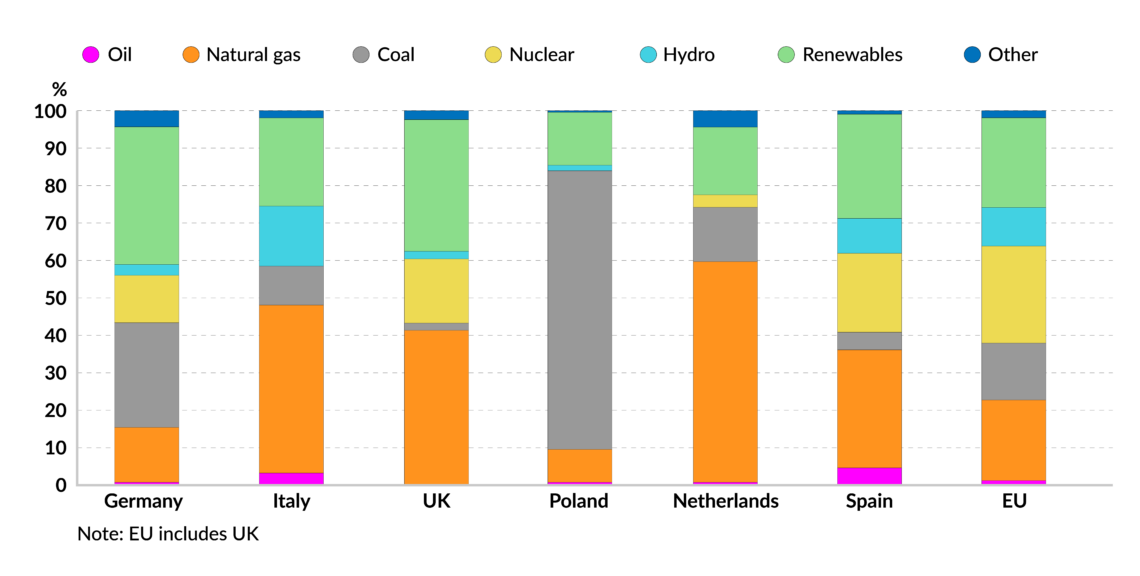

Such a combination of measures appears to be working. Overall, GHG emissions in the EU have fallen consistently since 1990 and were reduced by 23 percent between 1990 and 2018. However, to achieve its climate target, a huge task still lies ahead for the union. Whatever the EU has managed to accomplish during the last 30 years has to be done roughly three times faster in the next three decades to achieve the net-zero by 2050 emissions goal.

Facts & figures

Furthermore, underneath the trend, Europe is a multispeed energy region. At the EU level, more than 60 percent of electricity comes from carbon-free sources – renewables and nuclear – with the rest from gas, coal and oil. However, in countries like Germany and Poland, coal continues to play a critical role. In Poland, for example, 74 percent of electricity generation comes from coal. Taken together, Germany (35 percent) and Poland (25 percent) account for more than 60 percent of coal-fired electricity generation in the EU (plus the UK).

U.S. lesson

Like the EU, the U.S., the world’s second-largest CO2 emitter, has a mammoth task ahead. President Joe Biden’s ambitious climate pledge (to cut his country’s GHG emissions by at least half from 2005 levels by 2030) requires quadrupling the effort of recent years.

One speedy solution would be to phase out coal in electricity generation and replace it with natural gas.

However, the U.S. experience provides a valuable clue. The country has been able to reduce its emissions at an average of 1.1 percent yearly, over the period 2008-18, not because of a policy push to decarbonize but because of a coal-to-gas switching enabled by the shale gas revolution, which made gas more competitive than coal. While the growth in renewable energy has reduced U.S. CO2 emissions, the switch has played the biggest role in it.

Scenarios

While in the long term, all low-carbon energy technologies will play a role in decarbonizing the U.S. economy, it is not easy to see how the U.S. will reach the newly announced target by 2030 without natural gas. And it is not just the U.S.; in Europe, while a full spectrum of options is needed, one speedy solution would be to phase out coal in electricity generation and replace it with natural gas rather than wait for renewable energy expansion – especially as the gas infrastructure is already in place. In China, more work needs to be done to clean up the power sector as gas infrastructure is far from being on par with that in the U.S. and the EU, for instance.

In theory, decarbonizing the power sector would be best achieved by replacing fossil fuels with renewable generation. In practice, however, the intermittency problem makes this hard to accomplish in the short term. Natural gas generation capacity can complement wind and solar during seasonal variations unavailability and provide backup literally minute to minute in response to fluctuations in their outputs.

Put bluntly, fossil fuel baseload enables a rising share of clean power generation. In this respect, the energy transition towards net-zero by 2050 requires more, not less, integration between the fossil and the nonfossil segments of the energy system. This is, however, not where the debate seems to be heading today, particularly in Washington and Brussels.