Tighter monetary policy for fighting inflation? Really?

Their discourse notwithstanding, central bankers in the U.S. and the EU are not serious about fighting rising inflation.

In a nutshell

- The Fed and the ECB are not serious about fighting inflation

- Their monetary policies are becoming merely less expansionary

- The central banks’ interventions distort economies

Central bankers have finally realized that today’s inflation is neither accidental nor temporary, which is good news, of course. Regrettably, some of them had to learn some economics the hard way – both Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell and European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde have law degrees. One may argue that they could have chosen better economic experts and hoped for better choices in the future. That said, one would expect the authorities to be serious about fighting inflation now – rather than wait, indulge in some face-saving adjustments and hope that the problems gradually dissolve. Yet, we should not take this attitude for granted.

Reluctant steps

The American central bank’s course of action is simple and opaque at the same time. After relentlessly cutting the key interest rates since December 2018 and bringing them to zero in March 2020, the Fed raised them to 0.25 percent in March 2022 and to 0.75 percent in May. More rises have been announced soon to bring down price inflation to its long-run target (2 percent). As mentioned in previous reports, since the current rate of inflation is well above 8 percent, these moves have little to do with “tight monetary policy.” In reality, Chairman Powell is announcing a less expansionary monetary policy than in the past three quarters. One may even say that the real rate of interest has fallen further during that period. Not surprisingly, the Wall Street bubble is still there.

The main explanation for the Fed’s reluctance to take resolute action in fighting inflation is that the American economy is perhaps less healthy than it appears. True, a couple of months ago, Mr. Powell did say that the economy is strong enough to sustain a tighter monetary policy. But a few days ago, he also said that recession is possible.

Playing a weak hand

Certainly, an economy that still needs deeply negative real interest rates and where the personal savings rate is just 4.4 percent is hardly healthy. Indeed, Wall Street seems to know better. This author posits that the vastly publicized sell-offs experienced in May and early June 2022 did not stem from fears about future interest rates. Instead, it was the uncertainty related to the disruptions provoked by persisting inflation and, more generally, the economy’s fundamentals that mattered. In the first quarter of 2022, the United States economy increased at an annual rate of only 1.4 percent, the labor market is tight, and rising wage rates are squeezing profits.

The Fed is now facing the choice it should have made years ago.

In brief, the Fed is now facing the choice it should have made years ago. Chairman Powell can tackle inflation aggressively, forget about the short-run consequences for growth, and create the basis for a stronger economy in the future. Or he can opt to pursue a more accommodating approach, navigate by sight and raise interest rates gradually until the inflation rate drops below a given (so far undisclosed) threshold. This strategy was employed during the last quarter and, most probably, is what the Fed remains ready to do in the future.

If so, and unless economic growth turns negative, we may expect that investors will take their liquidity back to Wall Street, but also that the rate of inflation will drop only gradually and that its consequences (price distortions) will characterize years to come. Yet, this very strategy makes recession – or stagnation – even more likely.

Distorting the markets

More generally, and regardless of the strategy the American monetary authorities will follow, future developments will confirm the critical flaw typical of all policies centered on manipulating the rate of interest – namely, the illusion of knowing what the “ideal” rate of interest is.

Simply put, the ideal interest rate is the set of rates that clear the supply and the demand of credit. This, in turn, is influenced by the quantity of money in circulation. Of course, these rates would emerge when supply and demand and are free to interact absent all regulatory and policy interventions by the authorities, including the central banker. Therefore, to steer things in the right direction, the central banker should deregulate the credit and money markets, stop all kinds of intervention, wait for the market to do its job, and take note of the interest rates that would characterize the market transactions. And keep on doing nothing.

If the authorities intervene, this inevitably drives the interest rate away from where it should be. Distortions and false signaling follow. In essence, central authorities that mean to fight inflation should stop looking for the ideal interest. They should instead sit tight and watch. But this is what they are not going to do.

President Lagarde and her ‘experts’ now know that European inflation is no transitory phenomenon.

In the past, the authorities made it clear that they did want distortions and manipulated signaling, allegedly to avoid a systemic meltdown (the 2008 crisis), to restart growth (2009-2020) and to fight Covid (2020-2021). It is less clear why they would advocate yet another round of false pointers in the next couple of years, possibly longer, at the cost of creating further biases that would perhaps justify new rounds of active monetary policy and waves of instability. Preventing growth from stalling is a possible reason, of course. However, after Mr. Powell’s recent announcement, one doubts whether these authorities are truly committed to avoiding stagnation.

Sticking with illusions

Europe presents contradictions and self-inflicted wounds like those that have marked the American credit and monetary history for the past 15 years. Yet, Brussels and Frankfurt add two features of their own. The first regards the fact that in the past decade, the ECB policy aimed at easing the precarious position of several key countries where a public-finance crisis could have jeopardized the entire euro project. The list included Italy and Spain, with France not too far behind. The second feature is that President Lagarde and her “experts” now know that European inflation is no transitory phenomenon. She has announced that the ECB will stop buying government bonds in the third quarter 2022 and bring the nominal key interest rate to zero (currently -0.5 percent). However, Ms. Lagarde still argued that current inflation (8.1 percent in May) had little to do with the overly generous monetary policy decade.

Facts & figures

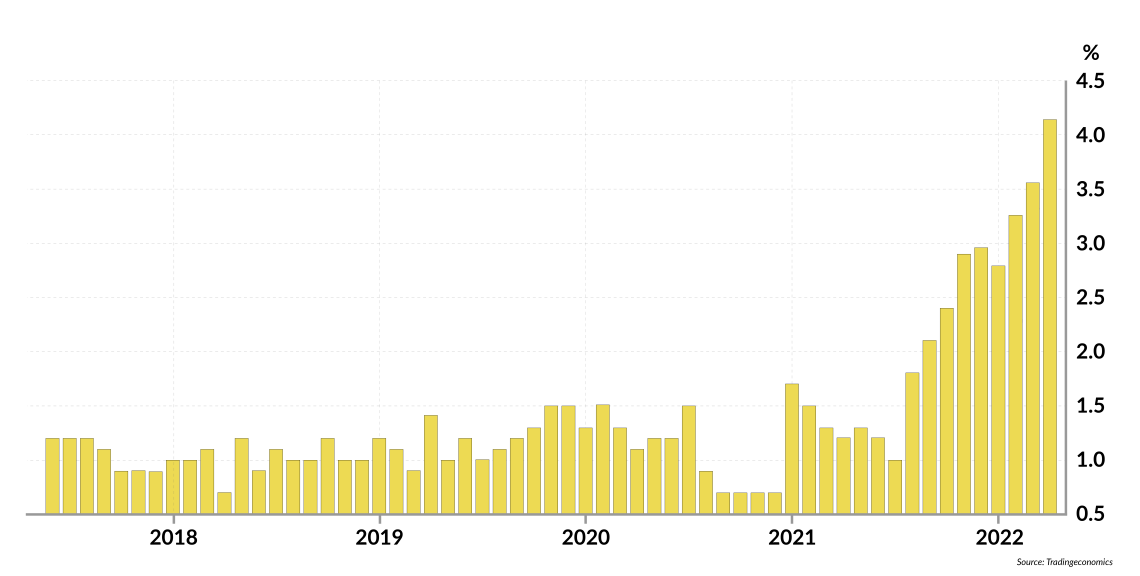

Core inflation rate in the EU, YOY

Indeed, she seems willing to pursue a monetary strategy that targets the so-called “neutral” rate of interest, i.e., what it takes to maximize output (GDP) and keep inflation stable. Interestingly enough, she has not given many details about her views on “maximum output” or the basis for her predictions about the “stable” inflation rate six months from now. Instead, she maintains that prices have risen due to supply shortages. The head of the ECB appears to suggest that the war in Ukraine has disrupted the global supply chain, caused unexpected inflation and now risked pulling the old continent into recession.

Scenarios

Nobody knows whether Ms. Lagarde thinks that future European growth and public indebtedness depend on the timing of Russia’s withdrawal or Ukraine’s surrender. The bottom line is that we should brace for a new, “creative” wave of public intervention to jump-start production in the eurozone and beyond, especially if the Russian invasion is not resolved soon.

To conclude, what can one expect for North America and the euro area? Market operators still seem to believe inflation will subside relatively soon and that central bankers should and will play an active and generous role. That explains why the interest rates on bonds and treasuries remain rather low.

For example, the yield curve of the U.S. Treasuries between three and 30 years is flat at about a 3.5 percent level. The same curve for the German Bund is almost flat, and ranges from about 1 percent (three-year bond) to about 1.4 percent (30-year bond).

Market operators are probably correct in judging that despite their statements the central bankers are not overly concerned about fighting inflation. Investors expect the Fed to stay “tough” but keep real interest rates negative, and the ECB to focus on protecting the sustainability of public debts in the eurozone, regardless of Ms. Lagarde’s announcements about the bond-purchase programs. On the other hand, market operators maybe overly optimistic in hoping that inflationary pressures will magically disappear.