Cyprus’s gas remains stranded

Technical and, above all, political obstacles block Cyprus’s way to becoming a natural gas producer and exporter. Some Mediterranean neighbors, including Turkey, complicate the problem.

In a nutshell

- 12 years since its discovery of offshore gas, Cyprus is yet to start production

- Its gas export potential is ample as the domestic market remains limited

- Turkey’s EEZ claims in the Eastern Mediterranean are one of the roadblocks

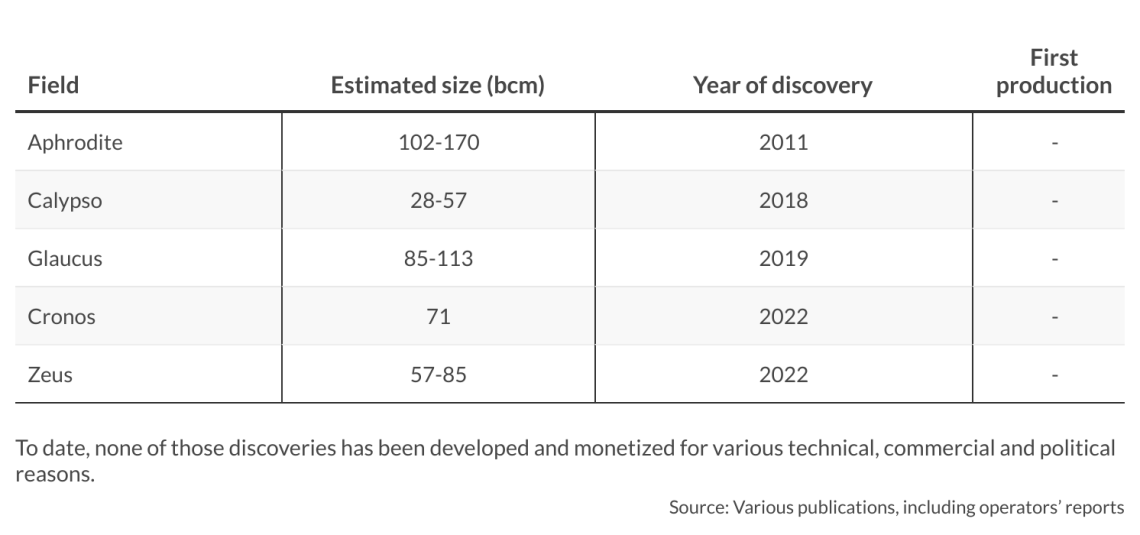

It has been 12 years since the discovery of Cyprus’s first and largest offshore gas field, Aphrodite. Four other findings followed between 2018 and 2022, made by some of the largest energy companies in the world. However, Cyprus has not produced – nor consumed – any natural gas to date.

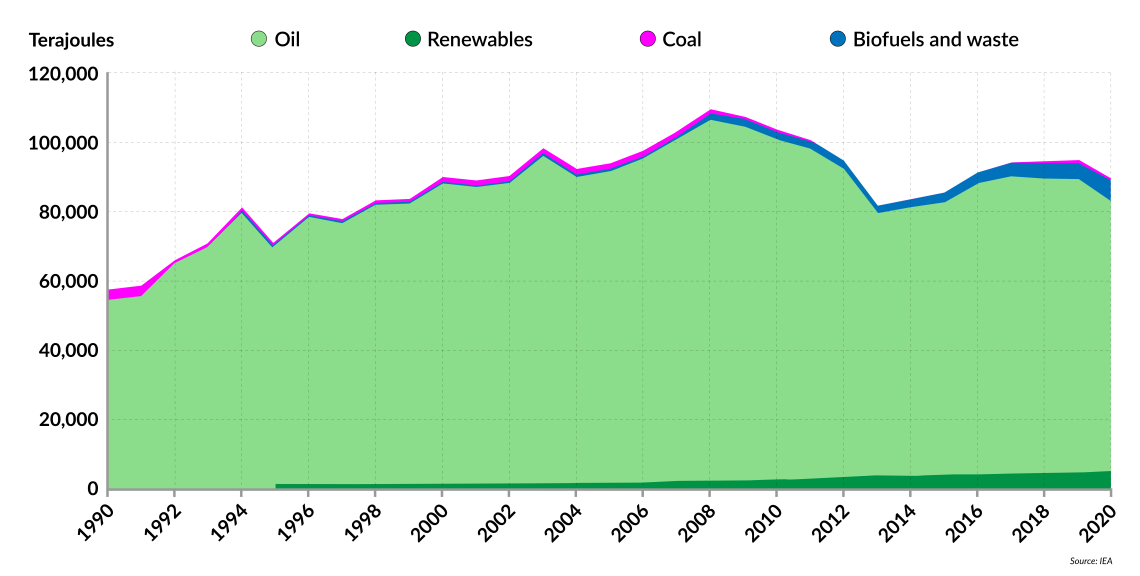

The country plans to change that and integrate gas into its oil-dominated energy mix by mid-2024. Using natural gas will help the country significantly reduce both its energy import bill and its carbon footprint and better align its energy strategy to the European Union’s regulations. However, Cyprus has had to turn to imports instead of domestic gas.

Facts & figures

Total energy supply (TES) by source, Cyprus 1990-2020

The EU counts on Cypriot gas

In 2020, Cyprus announced the construction of an LNG importing facility at the Vassiliko port. The imported gas will be piped to onshore infrastructure with links to the country’s energy grid, mainly for power generation. The project is partly funded by the EU and is expected to be completed in 2023.

That is seen as a temporary solution until production from domestic discoveries begins, helping to meet domestic needs and instigating exports. Even if Cyprus gasifies its entire economy and no further gas fields are discovered, there would still be sufficient resources left for exports, given the small size of the domestic market. (Neighboring Egypt, the largest gas market in Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean, has a record of occasionally suspending gas exports due to high domestic consumption.)

The EU is placing notable hope on Cypriot gas exports, which, along with gas from Israel and Egypt, “make the Eastern Mediterranean region a strategic partner for the EU in its effort to diversify its gas supply routes,” the European Commission stated in September 2021, even before its fallout with Russia in 2022.

However, Cyprus weighed several monetization options, including many export routes, with limited progress. A combination of technical, commercial and particularly political challenges characteristic to the Eastern Mediterranean region will continue to hamper the island’s gas plans. The EU’s support and continued interest from international energy companies have been pushing Cyprus closer to realizing its gas ambitions, but the road ahead remains mired in complexities and clashing interests.

The promising discovery of 2011

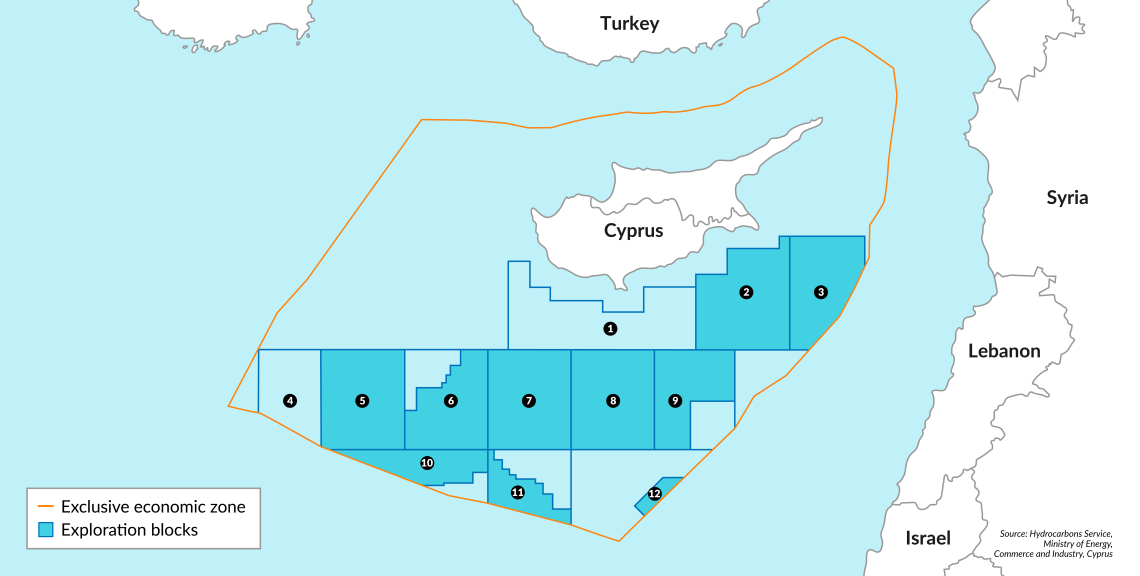

In 2007, before any significant hydrocarbon discoveries were made in the Levant Basin, the Cypriot government launched its first licensing round – offering 11 of its 13 offshore blocks to international investors. It attracted limited interest. Only three bids were submitted, partly because of protests from neighboring Turkey over the legitimacy of the licensing round, and partly because of high geological risk at the time since no prior discoveries had been made in the basin.

Geography limits the options that Cyprus can consider for transporting gas across the Mediterranean Sea.

One exploration license (Block 12) was awarded in 2008 to Noble Energy, a small, Houston-based company (acquired by Chevron in 2020), which was active in Israel and suspected that possible hydrocarbon accumulations in offshore Israel could extend northward to Cyprus. The company was proven correct: in 2011, Aphrodite, Cyprus’s first gas deposit, was found. Of its estimated volume, nearly 90 percent falls in Cypriot waters, the rest in Israeli waters, where it is known as the Yishai field.

Facts & figures

Republic of Cyprus, offshore exploration and exploitation licenses

Keen on capitalizing on the Aphrodite discovery, the Cypriot government launched four more licensing rounds (in 2012, 2016, 2018 and 2021), which resulted in blocks awarded to some of the world’s largest energy companies, including French major TotalEnergies, Italian Eni, Korean KOGAS, American ExxonMobil and Qatar Energy.

However, it was not until 2018 that another discovery, Calypso, was made by Eni in Block 6, followed by three more findings: Glaucus in 2019 and, in 2022, Cronos and Zeus. However, the estimated size of those discoveries indicates much smaller fields than Aphrodite.

Facts & figures

Cyprus’s geography limits its options for transporting gas across the Mediterranean Sea either by ship (LNG) or via a subsea pipeline – both solutions require substantial capital outlays. Furthermore, most of the island’s discoveries are very deep under water, geographically widely spread and feature complex geology; these factors increase the cost of their development. However, the political aspect has remained the most foiling obstacle.

Why the Aphrodite development is stuck

So far, the reasons that have caused delays in Aphrodite field development are commercial and political.

From the beginning, exporting gas from the field was the most viable monetization option, particularly given Cyprus’s lack of a domestic gas market. Initially, Aphrodite’s consortium considered an LNG export facility in Vassiliko. However, in 2013, further reservoir assessments revealed that the extractable volume of natural gas was a third of preliminary estimates and would not be sufficient to invest in an LNG plant without additional feed-in-stock from other fields in Cyprus or its neighbors. An LNG terminal requires a minimum volume of gas supply every year for the long term to justify the initial capital expenditure.

Read on why Brussels supports Cyprus’s gas plans

Averting a full-blown gas crisis in Europe

European gas markets ended 2022 in much better shape than they had been during the catastrophic first quarter. But they are not out of the woods yet.

Cyprus might see Egypt as a risky partner, given concerns about its political and economic stability, as well as its domestic gas prices, which are below those that exporters achieve in international markets.

Aphrodite’s partners’ preferred option is to transport gas from the field via a subsea pipeline to Shell’s underutilized West Delta Deep Marine facilities in offshore Egypt, where it would be treated. This option would save the partners the expense of building a new dedicated processing and production facility in Cyprus, significantly reducing development costs. The treated gas would then be transported to the Idku LNG plant in Egypt, also operated by Shell, for liquefaction and export or to be used domestically to meet growing gas demand there. With Shell being a partner in Aphrodite, this is commercially the most attractive option.

Politicians have different priorities

That option, however, is not appealing to the Cypriot government, which is keen on seeing its gas landing on the island first before being exported. Cyprus Energy, Commerce and Industry Minister Giorgios Papanastasiou was reported as saying that “Cyprus will prioritize its interests above all others.” Should any surplus remain, the government could consider exporting it, but the official emphasized that national interests would always come first.

Furthermore, Cyprus might see Egypt as a risky partner, given concerns about its political and economic stability, as well as its domestic gas prices, which are below those that exporters achieve in international markets.

Another problem that has hindered the development of the field is its partial extension into Israeli waters, which means that the field cannot be developed unless the two countries agree on a plan. Following the war in Ukraine and pressure from the EU, Cyprus and Israel promised to expedite a compromise in the ongoing Aphrodite dispute. No further information has been published about the status of the negotiations. Reaching a deal would remove a political bottleneck for Cyprus and the development of its flagship field.

Enter Turkey’s problem

For Cyprus to bypass Egypt and export directly to Europe, its most desirable target market, it would need to go either through a pipeline or LNG. The East Mediterranean Pipeline (EastMed), which would bring Israeli and Cypriot gas to Greece and then join the existing Poseidon pipeline across the Ionian Sea to Italy, has been proposed as the leading option. In 2013, the European Commission designated the proposal a “Project of Common Interest,” which links the energy systems of EU countries and can benefit from accelerated permitting procedures and funding. Since then, interested governments have signed a raft of agreements on the project. However, to date, it has failed to raise the necessary funding to cover its price tag of 6 billion euros.

In 2017, Greece, Cyprus, Italy and Israel signed a memorandum of understanding for the construction of the pipeline. Then, in 2020, the Cypriot and Israeli governments approved the construction, strongly backed by the United States at the time.

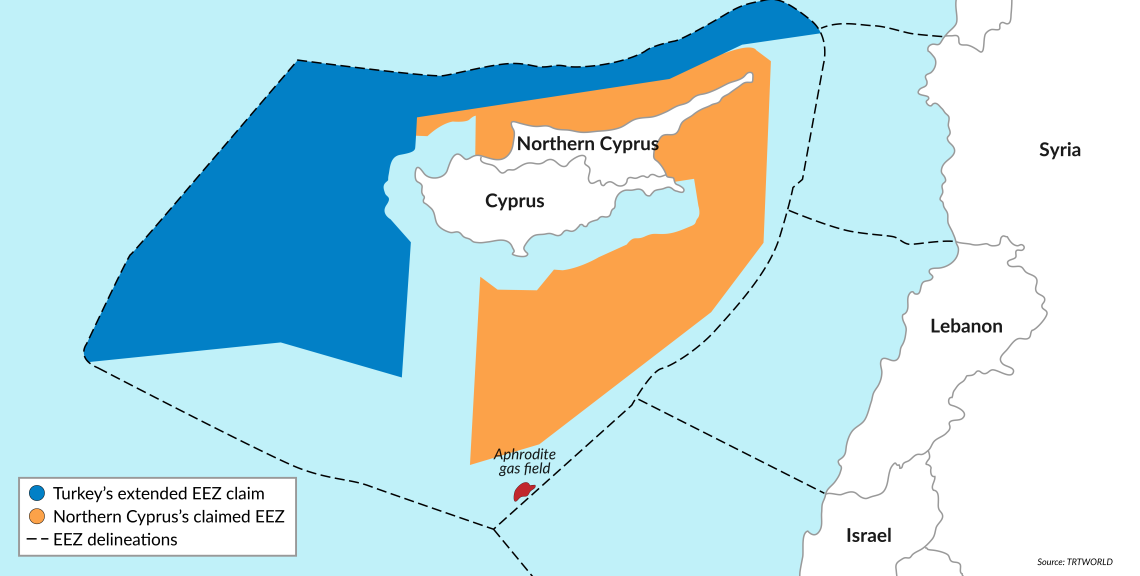

However, experts have described the project as a pipe dream all along, given the combination of technical and commercial challenges. The pipeline remains stranded at the feasibility-study stage, and the U.S. retracted its support early in 2022. While Washington did not officially publish any statement regarding its decision, it was motivated in part by a wish to avoid further destabilization of the region, given stiff Turkish resistance to the project. Furthermore, the proposed route traverses maritime territory that Turkey contests.

Turkey has overlapping territorial claims with Cyprus and has contested all the island’s claimed maritime borders.

In May 2023, during a parliamentary hearing in Italy, Claudio Descalzi, the CEO of Eni, which had an encounter with the Turkish navy during its drilling activities in 2018 offshore Cyprus, bluntly stated that “any agreement of this kind (exporting EastMed gas to Europe) must be made with Turkey; we cannot think that Israel, Cyprus and Greece can find an agreement without the participation of Turkey.”

Facts & figures

Marital exclusive economic zones (EEZs) from Turkey’s perspective

The political standoff between Cyprus and Turkey over Northern Cyprus remains a significant handicap for the two countries to pursue such a trade relationship. Although the conflict between the Greek-Cypriot and Turkish-Cypriot communities remains frozen, with little prospect of the situation deteriorating, Turkey has overlapping territorial claims with Cyprus and has contested all the island’s claimed maritime borders.

Scenarios

Unlikely: Cyprus bypasses Turkey and Egypt

Even though different LNG options have been proposed to allow Cyprus to bypass both Turkey and Egypt, none has moved beyond the discussion phase, given related technical and commercial challenges as well as the lack of funding. The proposals usually involve the inclusion of another player, typically Israel, to compensate for the lack of sufficient volumes in Cyprus that would be needed for the island to have its independent export facilities. For instance, one proposal would entail a pipeline to bring gas from Israel and Cyprus’s offshore gas fields to a floating LNG terminal in Cyprus, where the gas would be liquefied for export. The price tag of such a project has not been revealed, but it is unlikely to be competitive.

Likely: Egypt remains most practical partner

The closest discovery to starting production in Cyprus is most likely Aphrodite. For now, sending gas from the field to Egypt might be the most practical and fastest route for Cyprus to realize its gas export dream. Not surprisingly, that option is welcomed by Cairo, which is pursuing its regional gas hub ambition. Some might see it as far from being the best option for Cyprus but the best export option for the European island is yet to be identified.

Facts & figures

Cyprus facts

- The Republic of Cyprus is the third-largest and third-most populous island in the Mediterranean

- Since the Turkish Invasion of 1974, the Republic of Cyprus has had no control over one-third of the island’s territory in the northeast, inhabited by Turkish Cypriots and governed since 1983 by the internationally disputed state of Northern Cyprus (officially the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, or TRNC); Greek Cypriots inhabit Southern Cyprus

- Cyprus joined the EU in 2004 and became a eurozone member in 2008

- The Cypriot market is projected to consume less than 1 bcm of natural gas annually by 2030 – significantly less than Israel and Egypt will consume

- The Levant Basin encompasses approximately 83,000 square kilometers of the easternmost portion of the Mediterranean area, stretching from Israel to Syria and including Lebanon and Cyprus

- In 2010, Cyprus and Israel delineated their exclusive economic zones (EEZs) following amicable negotiations and submitted the coordinates to the United Nations. However, the maritime boundary agreement did not cover the framework in which cross-border resources should be developed

- Cyprus imports refined petroleum mainly from Greece, Israel, Turkey, Italy and the Netherlands