Eastern Mediterranean gas outlook gets murkier

After the 2009 and 2010 gas finds in the Eastern Mediterranean, many expected the region to become an energy hub. A decade later, myriad challenges connected to the EastMed pipeline remain – and the coronavirus has made a bad situation worse.

In a nutshell

- Gas markets faced challenges even before the pandemic

- The EU may now be less willing to fund the EastMed pipeline

- It would bring political rather than economic advantages

When the first gas discoveries in the Eastern Mediterranean were made more than a decade ago, many commentators expected the area to become an energy hub. However, market conditions have become worse over time, and the region is still mired in political uncertainty.

Right from the start, the list of challenges was long, and the number of state actors with conflicting interests grew. The coronavirus pandemic has simply made a bad situation worse. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), the resulting crisis will affect natural gas markets in the long term, and the medium-term outlook is highly uncertain.The EastMed pipeline, whose construction was announced a few years ago, would bring gas from the Eastern Mediterranean to Central Europe. It is now unclear whether the project will pass the market test.

Then there is the issue of funding. Covid-19 has left governments and private investors much poorer. The European Union might decide against spending its limited funds on projects with few benefits to its overall energy security agenda, instead of investing in green energy. Besides, Eastern Mediterranean gas reserves are very small on the global scale. Some politically motivated actors, however, may push for building the pipeline first, then check if it passes the market test later.

Facts & figures

Oil and gas in the Eastern Mediterranean

- Since the mid-1970s, the island of Cyprus has been divided between Greek-speaking Cyprus in the south, which is a member of the European Union, and Turkish-speaking Northern Cyprus, which is recognized solely by Turkey.

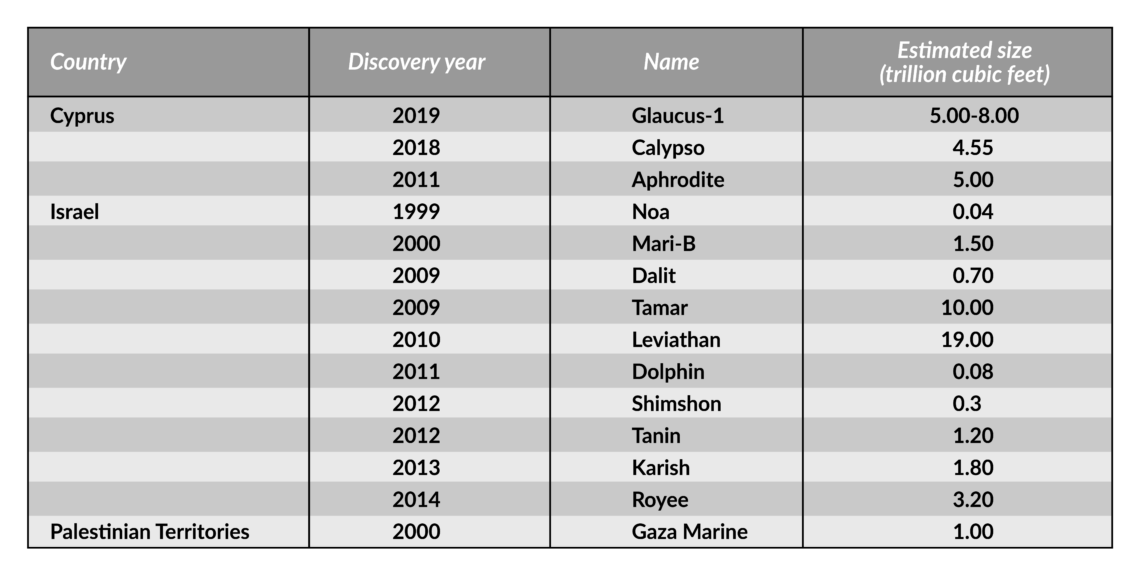

- According to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), the Levant Basin could hold 1.7 billion barrels of recoverable oil and Natural Gas Liquids (NGLs) and 122 trillion cubic feet of recoverable gas.

- As of 2019, 37% of EU gas imports come from Russia.

- Global natural gas consumption is heading for an estimated 4% drop in 2020, with Europe being the hardest-hit market.

- The EastMed pipeline is believed to be the longest underwater pipeline in the world.

- By 2025, Tamar is expected to supply between 50 and 80% of Israel’s gas needs.

Discoveries and cooperation

Israel announced significant offshore gas discoveries – the Tamar and Leviathan fields – in 2009 and 2010, which were hailed as two of the largest finds of the decade. Other, smaller discoveries were subsequently made in both Cyprus and Israel.

Israel is well ahead of its neighbors in exploiting offshore gas resources, though it prioritizes the domestic market over exports. In 2012, the Israeli administration decided to cap gas exports at only 40 percent of potential reserves to guarantee domestic supply for the next 25 years.

Cyprus is yet to exploit its discoveries. Lebanon’s hopes for a gas bonanza possibly contributed to the country’s economic demise since officials made plans on the basis of hypothetical revenues. One Lebanese bank estimated potential revenues at between $120 billion and $480 billion – and yet discoveries in the country have yet to be made.

It is now unclear whether the EastMed pipeline will pass the market test.

In 2013, Italian energy company Eni announced a major gas discovery in Egyptian waters. The Zohr field is believed to be the largest-ever gas discovery in the Mediterranean. Such findings raised the hopes of many states in the region, with Europe as a potential export destination.

Countries rushed to announce various Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs), committing to strengthening energy cooperation, including a Joint Declaration on Energy Cooperation. In 2019, Egypt, Jordan, Palestine, Israel, Cyprus, Greece and Italy launched the East Mediterranean Gas Forum (EMGF), a cooperation platform headquartered in Cairo, in the presence of the United States Secretary of Energy, as well as representatives from the EU, France and the World Bank. It was reported that France requested to join the forum and the U.S. asked to become a permanent observer. A year earlier, the EU and Egypt had entered an MoU for extended collaboration, due to the country’s growing role in “energy production and transit in the Euro-Mediterranean energy market”.

Some had even hoped that the newfound energy riches would encourage players across the region to overcome their long-standing animosity and cooperate politically.

Fundamental changes

Meanwhile, gas markets have undergone fundamental changes. Oversupply and downward pressure on prices had become notable even before the Covid-19 crisis.

The U.S. “shale revolution” started with shale gas, not oil, and transformed global and regional gas markets. American gas production staged an impressive recovery, reversing decades of decline. In 2009, the country overtook Russia to become the world’s largest gas producer – a position it has maintained since. Before shale, the U.S. was resigned to become a major importer of liquefied natural gas (LNG). With its new gas wealth, facilities built for imports were converted into export terminals. Suppliers counting on U.S. gas demand had to look to Europe or Asia to export. Since 2016, the U.S. has been shipping LNG to Europe, Asia and South America.

The global gas market was also expanding. While most transit still happens via pipeline, LNG trade expanded by nearly 13 percent in 2019, marking the strongest growth since 2011. According to the IEA, the development bodes well for natural gas supply security.

Floating Regasification and Storage Units (FRSUs) have facilitated new imports into the Middle East, North Africa and elsewhere. (FRSUs do not require permanent mooring and offloading infrastructure to be built at high upfront cost, unlike other methods.) On the supply side, floating liquefaction (FLNG) plants eased access to resources previously considered difficult to monetize.

In 2017, Qatar announced that it would lift the moratorium on production in its giant North Field. The country also announced plans to increase liquefaction capacity, which will translate into major export growth of low-cost LNG.

The trends discussed above will only intensify competition between gas exporters, and between pipeline gas and LNG. Investors will consider these factors before committing to building new infrastructure.

Facts & figures

Core problem

The Eastern Mediterranean is a politically fragmented region. Official “cooperation” tends to omit at least one key player, thereby limiting the region’s potential as a gas hub.

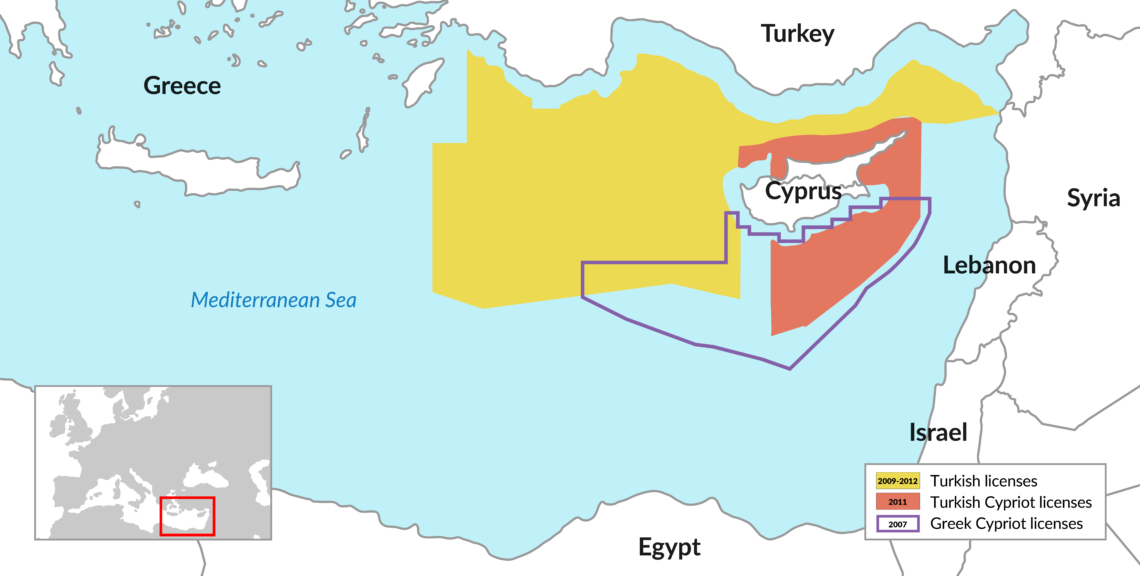

Syria has been in the midst of a civil war since 2010. Israel and Lebanon are still officially at war with each other, and have conflicting claims over their maritime boundaries. There is no love lost between Turkey and Cyprus either. Because of maritime border conflicts, Turkey already has disrupted the exploration activities of international oil companies in Cyprus’ exclusive economic zone (EEZ).

To complicate matters further, in December 2019, Turkey and Libya reached a maritime deal that creates an EEZ running from Turkey’s southern Mediterranean shore to Libya’s northeast coast. The deal has been vehemently condemned by Greece and Cyprus. In parallel, Israel and Egypt – which supports the insurgent forces fighting the Ankara-backed Libyan government – have expressed serious concerns about the project’s implications for stability in the region.

International gas markets were structurally oversupplied long before the pandemic.

The deal also interferes with export plans to Europe, including the EastMed pipeline – a 1,900-kilometer pipeline project (1,300 km offshore and 600 km onshore) to transport natural gas from Cyprus and Israel to Greece and Italy. Turkey openly opposes the initiative.

In June this year, Turkey caused another regional outcry when it published a map showing the area to which it claims sovereignty. The area clearly overlaps with a large part of Cyprus’s EEZ. Turkey’s state-owned Turkiye Petrolleri Anonim Ortakligi (TPAO) has also carried out drilling activity in Cyprus’ Block 6, which is jointly held by Eni and Total, prompting international condemnation. The move was clearly an act of provocation – TPAO is unlikely to have the technical and financial capability to develop any potential discoveries.

The Covid impact

On their own, the political intricacies of the region were enough to compromise monetization prospects for natural gas. Covid-19 simply darkened the outlook. Because of the rapid growth in global LNG export capacity, international gas markets were structurally oversupplied long before the pandemic. The economic slowdown brought about by the crisis has aggravated this situation. In Europe especially, the demand shock from Covid-19 lockdowns has pushed European gas prices to record lows. According to the IEA, the continent is the hardest-hit market, with a 7 percent decline.

The impact of the pandemic has been particularly severe on the oil and gas industry, which is now making significant reductions in capital expenditure and delaying or canceling projects. ExxonMobil and Eni, for instance, announced that they would delay all offshore drilling in Cyprus for at least one year.

Meanwhile, demand for gas in Israel is expected to fall by up to 9 percent over the next 18 months, according to S&P Platts, while Egypt halted exports from its only operational LNG plant. After an unsuccessful first exploration attempt in April, Lebanon postponed (for the third time) its second offshore licensing round, citing the impact of the coronavirus epidemic on the oil and gas industry. No new date was set for the round but the government hopes to hold it before the end of 2021.

Scenarios

The EastMed pipeline has been included on the European Commission’s list of Projects of Common Interest (PCI), which are defined as “key cross border infrastructure projects that link the energy systems of EU countries.” They “are intended to help the EU achieve its energy policy and climate objectives: affordable, secure and sustainable energy for all citizens, and the long-term decarbonization of the economy in accordance with the Paris Agreement.”

Apart from linking the energy systems of EU countries, it is difficult to see how the EastMed project meets the criteria defined above. With a price tag of approximately 6 billion euros, the pipeline would initially supply around 2 percent of the EU’s total gas imports, later set to increase by another 2 percent. A final investment decision was expected in 2022; and the pipeline was meant to start delivering gas into Europe’s network in 2025.

These timelines, however, are unlikely to be met under the current circumstances. The contribution to Europe’s energy supply security appears marginal. The push for the EastMed pipeline seems mostly politically motivated. The Greek state television channel ERT has referred to the project as a “protective shield against Turkish provocations.”