Scenarios for Georgieva’s leadership of the IMF

The new head of the IMF, Kristalina Georgieva wants to redefine its aims to address climate change, economic fairness, and gender equality. If she succeeds, the IMF could transform from an economic reform-minded lender of the last resort to a definer of global morality.

In a nutshell

- Kristalina Georgieva has long focused on environmental issues

- At the IMF, the Bulgarian economist is pushing a social agenda

- The IMF's role as a central actor in global finance may be threatened

On October 1, 2019, Bulgarian economist Kristalina Georgieva began her five-year mandate as managing director and chair of the executive board of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The former CEO of the World Bank succeeds Christine Lagarde, who, for her part, recently replaced Mario Draghi as president of the European Central Bank (ECB).

The changes at the helms of these major supranational institutions are more than just another game of musical chairs. They could redistribute power among the key players in global economic governance for the long term.

Whether the reshuffle will serve the IMF is another question. As former IMF official Eswar Prasad points out, the primary challenge for the new managing director will be to maintain the organization’s influence, relevance and legitimacy just as multilateralism is breaking down amid heightened trade tensions and shifting geopolitical alliances.

Furthermore, Ms. Georgieva takes the reins of the Fund at a time when the world economy is under increased stress, to the point that the IMF’s latest World Economic Outlook warns of substantial risks of a global recession in 2020. Historic levels of debt, weak investment and decelerating growth rates in both developing and advanced countries are but a few of the “fractures” the new chief mentioned in her alarming first speech as head of the organization.

Adversity as opportunity

It is precisely during periods of turmoil that the IMF has expanded its power the most. The institution drew an unexpected benefit from the 2008 financial debacle, even if it had not seen coming the severest global economic crisis since the Great Depression of the 1930s.

It took a cascade of systemic crises to lift the IMF to the status of the world’s number-one emergency lender again.

In the run-up to the 2008 crash, the Fund seemed almost at the end of its rope. As IMF historian Stephen Nelson recalls, by 2007, interest payments on outstanding loans – the “institution’s lifeblood” – had dried up to the point that the executive board envisaged a staff cut of 15 percent. Even the sale of part of the IMF’s gold reserves was considered just to ensure the organization remained solvent. In the pre-crisis decade, the IMF was sledding down a “path to irrelevance,” Mr. Nelson writes. For other observers, the institution had lost “its sense of standing and purpose.” Economist Barry Eichengreen went as far as to compare it to a “rudderless ship adrift on a sea of liquidities.”

It took a cascade of systemic crises (including one that threatened to destroy the eurozone and its currency) and some unconventional leaders to lift the IMF to the status of the world’s number-one emergency lender again. When the storm let loose over financial markets, IMF members rapidly agreed to stretch the Fund’s crisis “firewall,” which today reaches a vertiginous height of almost $1 trillion.

At the same time, the IMF considerably expanded its traditional scope of action (conditional lending, technical assistance to member states, research, surveillance and forecasting) to become a key actor in shaping economic, fiscal and monetary policymaking in the countries placed under its tutelage. A handful of European countries (Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Cyprus) were in the lot. In the context of the sovereign debt crisis, the rescue packages of the Troika, in which the IMF acted alongside the European Commission and the European Central Bank, were conditional on the adoption of harsh budgetary austerity measures the governments concerned had to impose on their populations.

Even if, later on, the IMF came to acknowledge that notable miscalculations had been made in designing those unpopular programs, the organization remained untouched as the only game in town in global crisis prevention and management. Under the leadership of Ms. Lagarde, the Fund’s original goals (facilitating international trade, removing market barriers and fostering global monetary cooperation, among others) were progressively enlarged to include virtually any issues related to global macroeconomic and financial stability.

Better policies for better lives

With another economic downturn looming, Ms. Georgieva promises to “further strengthen the Fund,” by scaling up its financial safety net even more and redefining its core goals. Climate risks, technological change and inequalities have been cited as the three main challenges to be addressed by her aggressive action plan.

Facts & figures

It is early days, but the new IMF boss could well become the one who precipitates a paradigm shift within the institution that her predecessors had already initiated after the 2008 crisis. It is a move away from the free-market-oriented worldview characterizing the IMF’s activities (sometimes referred to as “embedded liberalism”) and toward an ever more dirigiste and paternalistic stance – a kind of benevolent interventionist technocracy, aiming at designing policies that “build stronger economies” and “improve people’s lives.”

To implement her ambitious-sounding program, Ms. Georgieva is counting on what she calls the IMF’s “world-class staff”: approximately 2,700 employees from 150 countries. The Fund’s research team alone, led by the young, Harvard Professor Gita Gopinath, stands out in the academic world with an army of economists and policy advisors holding graduate degrees from the highest-ranked American universities.

Career builder

Not long after finishing her postgraduate studies, Ms. Georgieva joined the World Bank in 1993 and rose through the ranks to become the group’s vice president and corporate secretary in 2008. In early 2017, after a six-year detour to the European Union, she became the World Bank’s CEO and even jumped in as acting president during a three-month interim period in 2019.

Ms. Georgieva’s nomination at the IMF has received both acclaim and criticism. In her Brussels years, she won a reputation above all in her role as EU commissioner for international cooperation, humanitarian aid and crisis response (2010-2014). Right away, in 2010, she was named “European of the year” and “Commissioner of the year.” In 2014, she was appointed EU Commissioner for budget and human resources. At the same time, she was named vice president within the Juncker Commission. This prestigious post is normally reserved for the high representative of the Union for foreign affairs and security policy, a title she had coveted but could not receive because of political uncertainties in her home country.

Already then, some critics held her long service as a bureaucrat against her. She was the European Commission’s first vice president who never served as a national minister. In fact, she has never been democratically elected at any level.

In Brussels, Ms. Georgieva was criticized for leaving her staff in the middle of the tumultuous Multiannual Financial Framework negotiations.

Ms. Georgieva resigned from the Commission in 2016, two years before the end of her term as EU budget commissioner. After a lengthy shadow campaign, she made a last-minute entry into the race for the high-status post of United Nations secretary-general. In the end she lost out and went on to the World Bank. In Brussels, though, she was criticized for leaving her staff in the middle of the tumultuous Multiannual Financial Framework negotiations, whose oversight was at the heart of her job as head of the European budget.

Despite her reputation as a collector of top jobs, her name popped up again for the post of EU Commission president in the summer of 2019, after the failure of the European People’s Party (EPP) to impose its candidate, Manfred Weber, as Jean-Claude Juncker’s successor. The EPP, however, is reported to have strongly objected to Ms. Georgieva’s nomination, given her alleged affinities with Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban and his controversial Fidesz party, which was temporarily suspended from the EPP over EU rule of law violations.

Squaring the circle

Her recent appointment at the helm of the IMF confirms that a few missed opportunities have not kept Ms. Georgieva from navigating her ascent to the top of the highest corridors of power. This time, however, she may be walking a thin tightrope. Mitigating climate change while stimulating global economic growth and tackling inequality promises to be a real conundrum.

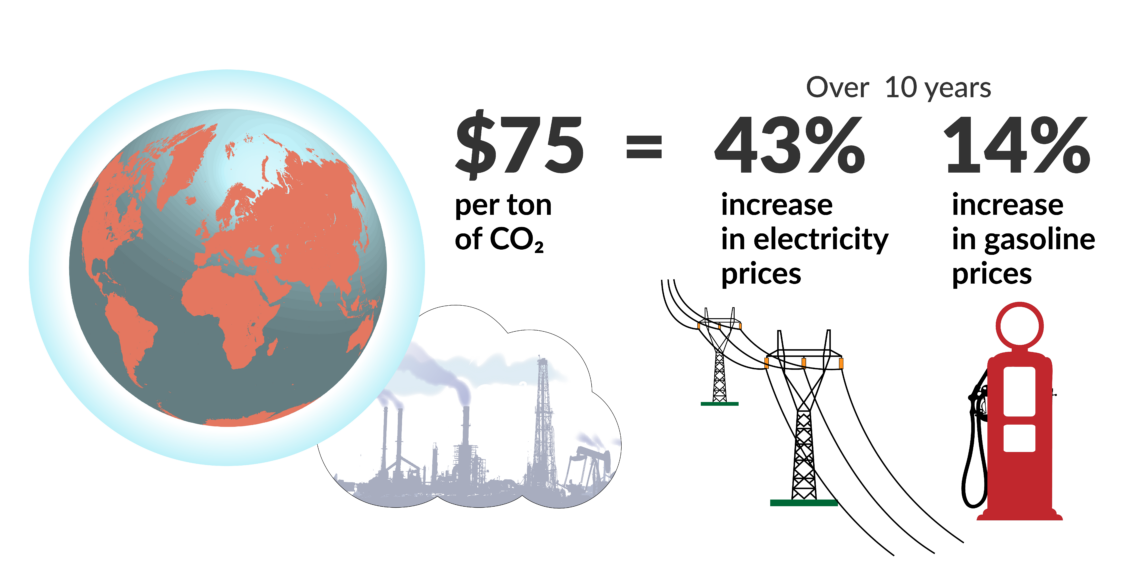

In the first Fiscal Monitor published under her leadership, the IMF urges governments around the world to introduce an “immediate” and rapidly increasing “global carbon tax” that will make households’ electricity bills jump by 43 percent and gasoline prices by 14 percent on average over the next decade. Achieving social acceptance for such measures will be a significant challenge, especially since their effectiveness for reducing climate change is questionable. As shown by the recent political backlash in several emerging market economies, many of which already struggle with IMF-imposed austerity policies, a very small rise in domestic fuel and petrol duties (or, as in the case of Ecuador, a cancellation of fuel subsidies) could trigger weeks of strikes and mass protests, violent enough to bring down a government.

Fuel riots do not occur in fragile settings only, however. In 2018, a minor fuel-tax increase sparked the French Yellow Vest movement, which quickly aimed to challenge government authority in the long term, by disrupting social and economic life in the EU’s second-largest economy.

Facts & figures

Kristalina Georgieva

- Ms. Georgieva is the first IMF managing director from Eastern Europe (Bulgaria) and from an emerging market

- She is the second woman to become managing director of the IMF

- Her five-year term started on October 1, 2019

- She is overseeing $1 trillion, the total amount the IMF is able to lend its member countries, and some 2,700 staff from more than 140 countries

- She is cochair of the Global Commission on Adaptation and the UN Secretary-General’s High-Level Panel on Humanitarian Financing

- She is the first author of a Bulgarian textbook on microeconomics

- She has authored or coauthored more than 100 publications on environmental and economic policy topics

- She has lectured at Harvard University, MIT, the London School of Economics and China’s Tsinghua University

- She was CEO of the World Bank from January 2017-October 2019. She was also interim president of the organization for three months

- From 2014-2016 she was European Union Vice President for Budget and Human Resources

- In the EU budget role, she managed some $175 billion and 33,000 staff

- From 2010-2013 she was European Commissioner for International Cooperation, Humanitarian Aid and Crisis Response

- Between 1993 and 2010, she held various positions at the World Bank, including country director for the Russian Federation (2004-2007), director for sustainable development (2007-2008) and vice president and corporate secretary (2008-2010)

- She holds a PhD and a Master’s degree in Economic Science from the University of National and World Economy (formerly the Karl Marx Higher Institute of Economics) in Sofia, Bulgaria

Source: IMF

Another tough nut to crack for Ms. Georgieva will be refocusing the IMF’s mandate to deal with severe debt crises in emerging markets. The most pressing case is Argentina, whose piles of debt have pushed the country to the brink of default for the second time in less than 20 years. Both then and now, the IMF loans (the most generous the Fund has ever granted to a member) seem only to “postpone the inevitable and, worse, to exacerbate the ultimate collapse,” insists former IMF chief economist Kenneth Rogoff.

Organized hypocrisy

Ms. Georgieva is the first managing director in the Fund’s 75-year history to come from an emerging country and one could expect that amending the institution’s voting system will be high on her agenda. For a long time, country representation at the IMF has been denounced as outdated, imperialistic and unfair. Despite reforms in recent years, the voices of Western nations still tend to weigh more than those of the world’s largest emerging economies. For example, Germany and France have 268 and 204 votes, respectively, while India only has 132.

Ms. Georgieva’s recruitment itself was exemplary of European predominance in IMF affairs. The nomination of the 66-year-old (for which the IMF had to remove an internal rule according to which a candidate aged 65 or more cannot be appointed managing director) is said to have been orchestrated beforehand by political decision-makers from a small group of EU economies, France at the forefront, with Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire coordinating the discussions on behalf of his peers.

Yet the Fund had promised that this time the recruiting process would be “open, transparent and merit-based,” so that any candidate from any of the 189 IMF member countries could stand a chance to become the organization’s next leader – as long as he or she had a “distinguished record” in senior-level policymaking.

Ms. Georgieva’s dream to ‘improve people’s lives’ should be taken with a grain of salt.

It seems obvious that the old unwritten Bretton Woods agreement between Europe and the United States, according to which leadership of the IMF is reserved to a European, while that of the World Bank goes to an American, has been applied once again. A glance at the nationalities of the Fund’s managing directors (in order since 1946: Belgian, Swedish, Swedish, French, Dutch, French, French, German, Spanish, French, French, and now Bulgarian, but based on a French proposal) is enough to realize that the new growth drivers of the world economy are consistently ignored.

Political scientist Catherine Weaver uses the term “organized hypocrisy” to describe the decoupling between talk and action typical for these (often untrusted and unloved) technocratic organizations. The gap between what they say and what they do is nowhere more flagrant than in the World Bank’s ambition, reiterated relentlessly for decades, to achieve a “world free of poverty,” Ms. Weaver argues.

Scenarios

Ms. Georgieva’s dream to “improve people’s lives” should therefore be taken with a grain of salt. As the new head of the IMF, she has become one of the most powerful women in the world. How she is going to use that power is the crucial question.

At a conference held earlier this year, while she was still World Bank CEO, she told a journalist that, under her guidance, virtually all of the institution’s funding projects are being evaluated through a “gender lens.” “I will not hold a meeting in which I will not talk about the inclusion of women,” she pledged in the interview.

The promotion of gender equality will likely be a top priority of her IMF agenda as well. To “walk her talk,” as she says, she might want to strive for gender parity, for a start, in the high ranks of the IMF – a policy very much in the mood of the time, which Ms. Lagarde had already favored during her reign.

More importantly, Ms. Georgieva might revolutionize the IMF’s position on structural conditionality, by making loans to beneficiary countries conditional on a large-scale promotion of gender equality (supposed to be at the heart of what she calls the “smart” economy), rather than the pursuit of traditional economic or fiscal performance criteria.

Time will tell whether this is just a shift in rhetoric or a true ideological move at the top of the organization. In the latter case, the Fund could mutate into a global definer of societal morality. Striving to become a kind of equality-promoting international aid agency with great communication skills and lofty values, empowered by a unique arsenal of financial and material resources, Ms. Georgieva’s IMF could increasingly resemble a World Bank 2.0.

In the future, the relevance of the IMF could be at stake if, in the course of that evolution, it ceased to be the central actor in global financial governance, whose role as tough lender of last resort – giving countries in severe distress renewed access to private credit markets in exchange for a commitment to fiscal soundness – can prove crucial in times of systemic crises.