India revives its standing among neighbors

New Delhi has used economic levers to bring regional partners closer, taking advantage of a passive China.

In a nutshell

- South Asian states are turning to India for economic aid

- China has dented its image as a reliable partner

- Areas of friction will include military ties and migration

After nearly two decades of ups and downs in the region, India has begun to reassert its influence among its smaller neighbors. China has failed to show up as partners like Pakistan and Sri Lanka face economic crises, leaving an opportunity for New Delhi to step in.

For a five-year period beginning in 2011, India’s influence in South Asia was under strain. A bilateral summit with Bangladesh was scrapped after the collapse of a planned border settlement. Sri Lanka announced that Chinese nuclear submarines would be allowed to dock in its ports, crossing what New Delhi considered a red line for its regional security. In 2013, the Maldives elected a government that sought to replace India with China as its primary partner. And Nepal tried to pass a constitution that marginalized half of its population with ethnic links to India, leading an angry New Delhi to impose a de facto blockade in 2015.

While India’s ties in the region periodically become volatile, many of these problems were a consequence of internal weaknesses, as well as a perception that China now represented a well-heeled alternative partner.

Sphere of influence

Today, India’s standing in South Asia could not be more different. Global economic problems weigh on all its neighbors, the most spectacular case being Sri Lanka, which has been driven into bankruptcy. India is now treated by many of these countries as an economic savior, thanks both to New Delhi’s relatively well-managed finances and China’s puzzling passivity.

Even regional rival Pakistan is so entangled in energy crises and domestic political strife that it is mainly a threat to itself. China-leaning governments in Nepal, the Maldives and Sri Lanka have been replaced, while Bangladeshi Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina Wazed remains steadfast in her support for India.

This reversal has partly occurred because of domestic political developments. The Maldives’ authoritarian, pro-China government of Abdulla Yameen was defeated in the 2018 elections, and a similar fate befell Nepalese prime minister KP Sharma Oli three years later, when his own party turned against him over attempts to confront India. Mr. Oli’s anti-India campaign was quixotic; Nepal and India virtually share an economy, with one in five Nepali citizens working in India thanks to an automatic right to residency there.

Sri Lankan U-turn

The most remarkable turnaround has been in Sri Lanka. After winning the country’s civil war, former President Mahinda Rajapaksa rebuffed pressure from New Delhi to conclude a political settlement with the defeated Tamil minority, instead turning to China. Also attractive were billions of dollars in infrastructure contracts to Chinese firms, with a sizeable portion of the funds allegedly diverted to cronies. India’s firms were sidelined, and its influence dwindled. Even other partners like Japan were shown the door, with their contracts and aid projects unceremoniously handed over to China.

The political collapse of the Rajapaksa regime was precipitated by an inability to handle the sudden changes in the global economy. A sharp rise in energy prices, due partly to war in Ukraine, saw the costs of the country’s oil and fertilizer imports spike sharply. Like in all South Asian countries, rising prices meant that foreign exchange reserves dwindled, the local currency lost value, imports became even more expensive, and severe shortages and inflation followed. Sri Lanka and Pakistan aggravated their situations with poor economic policies. Sri Lanka, for example, tried to save on fertilizer imports by transitioning to organic agriculture, wrecking its farm sector.

India’s hope is for all its neighbors to naturally turn to New Delhi on any major decisions with economic and security implications.

Even more striking was how badly their geopolitical plays failed. Islamabad and Colombo had gambled heavily on China. But when the chips were down, Beijing declined to provide any emergency financial assistance – offering only to roll over existing debts but otherwise pointing the way to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Both the United States and Japan brusquely declined Sri Lanka’s pleas for help. Pakistan, meanwhile, had even ruined its relationships with Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, formerly reliable sources of aid.

Bangladesh, South Asia’s second-largest economy, has done a better job of handling the energy crisis, though its foreign exchange reserves have fallen from $60 billion to less than $40 billion as it tried to defend its currency. Sensibly, it went to the IMF quickly, increasing prices and introducing power rationing early on. Accordingly, its condition is now more belt-tightening, less firefighting.

Helping hand

India has stepped in to fill the resulting void. New Delhi shipped nearly $5 billion worth of fuel, food, fertilizer and medicine to Sri Lanka to prevent a total collapse. It has provided that assistance under lines of credit, but is structured in a way that does not eat into Sri Lanka’s depleted dollar reserves.

Nepalese prime minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal met with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi in July, promising to bury the hatchet over any outstanding disputes. Bangladesh’s own leader visited India in early September and agreed to start negotiations for a bilateral trade agreement and consider arms purchases from India. Mr. Modi’s policy toward Pakistan has remained one of studied indifference, but nonetheless, trade between the two countries has doubled as Pakistanis seek cheaper Indian imports. New Delhi introduced restrictions on wheat exports in July but exempted most neighboring countries, and even shipped wheat to Afghanistan and Myanmar.

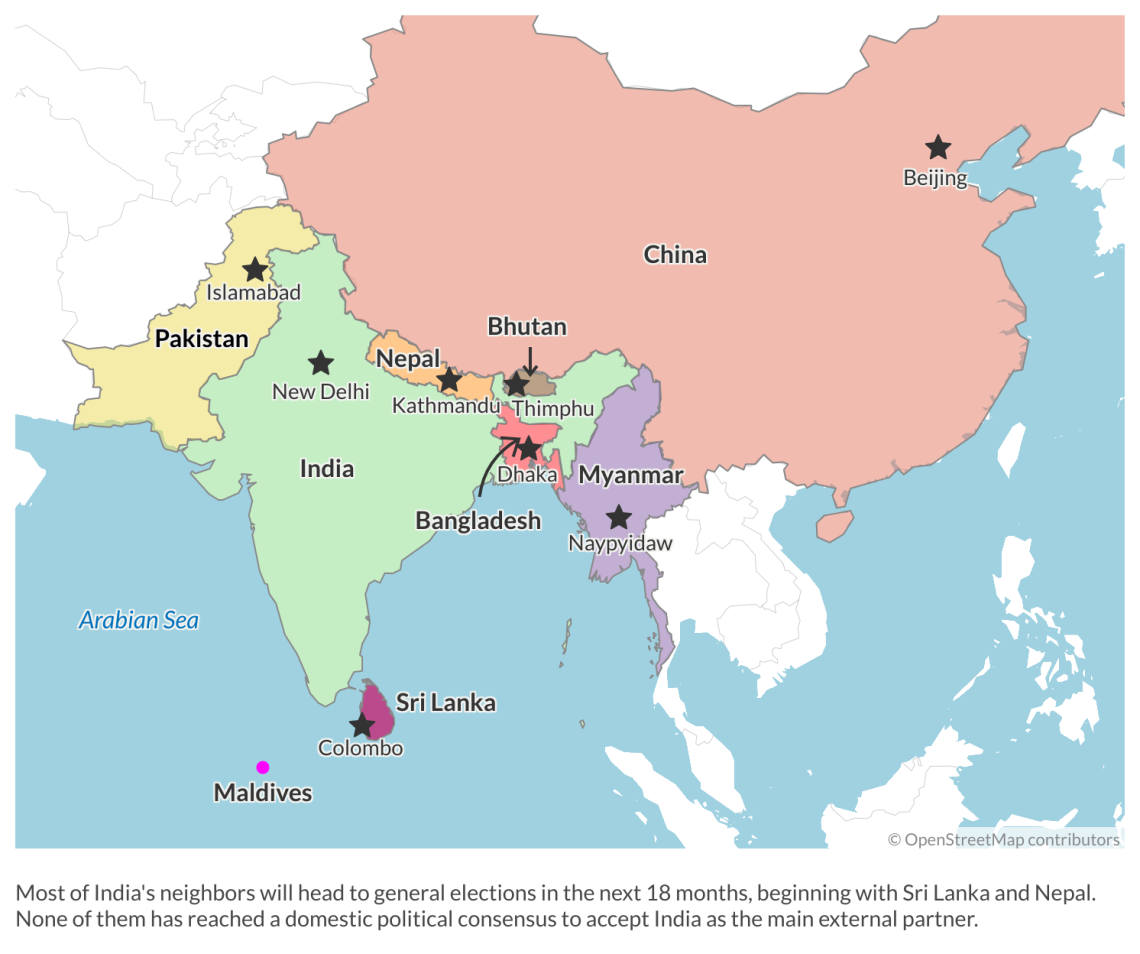

None of this means India is assured of primacy in South Asia, even for the near future. Most of its neighbors will head to general elections during the next 18 months, with Sri Lanka and Nepal first up. There is hardly a domestic political consensus within these countries to accept India as the main external partner. In the Maldives, for example, former President Yameen is the main opposition candidate, and has made “India Out” a campaign slogan.

China has a badly dented image. Its practice of building nonviable infrastructure projects at extravagant prices and debt levels has tainted the Belt and Road Initiative. Its failure to assist Sri Lanka during its time of urgent need was particularly damaging. Far fewer governments now see Beijing as a reliable partner; even in longtime ally Pakistan, there is a sentiment that the country was too quick to jettison its relationship with the U.S. However, Indian officials note that China continues to hold many levers of power in these countries, through well-greased personal networks in the bureaucracy, political class and military.

Facts & figures

The Modi government is trying to create more tangible grounds for smaller neighbors to automatically look to India. The most important is strengthening connectivity – and through that, trade and investment – with Bangladesh and Nepal. This includes not only road and rail corridors but also linked power grids and smart passes for container traffic. Indian firms are being encouraged to invest in these countries, although so far with limited success.

India and China are neck and neck when it comes to trade with Bangladesh. Sri Lanka’s commerce with China, on the other hand, dwarfs its trade with India, a dynamic New Delhi hopes to partially correct with its new investments. A more difficult task is dislodging entrenched Chinese influence in the militaries of states like Bangladesh. There, India also faces a limited ability to produce weapons and a quiet fear among potential partners of ceding agency in security matters to South Asia’s largest country.

Scenarios

India’s hope is for all its neighbors to naturally turn to New Delhi on any major decisions with economic and security implications – and for domestic stakeholders in those countries to also share that impulse. The reality is still far from that ideal. But if all goes according to plan, India will have reestablished its primacy in Sri Lanka and consolidated its position with Bangladesh and Nepal. If the coming elections in the region do not bring any surprises, China’s present setbacks will give India at least three to four years of breathing space, allowing it to concentrate on the hard stuff of logistics parks and customs points.

At best, India will likely be only partially successful in its endeavor. Sri Lanka remains politically unstable, and New Delhi is worried about extreme leftist groups growing ascendant as the establishment loses legitimacy. Bangladesh’s present government is friendly, but Sheikh Hasina is 74 and her succession plan is unclear. Uncertainties about Nepal revolve largely around its multiple political factions and the surprises their squabbling can bring. What is clear is that domestic factors in each of these countries will be the main source of concern for India, rather than Chinese influence, as has been the case for the past 15 years.

India’s desire to strengthen its sphere of influence also raises deeper and more difficult sources of friction. These include water sharing and aquifer management issues, which climate change is moving up the priority. India also lacks a suitable immigration policy, given the porosity of its borders with most neighbors, an area where the Modi government is ideologically ill-equipped.

Finally, it will find cause to take regionalism more seriously. South Asia has a number of relevant bodies – most of which are derelict or forums for mere talk, largely because New Delhi prefers to work on a bilateral basis. China’s rise has made India realize that complacency is no longer an option, even along its own borders.