India’s foreign currency reserves fairy tale

Once chronically short of dollars and pounds, India today has the fourth-largest foreign exchange reserves in the world. New Delhi’s challenge is modernizing its reserve management and leveraging this bounty to further the country’s international ambitions.

In a nutshell

- Unexpectedly, India is flush in foreign currency reserves

- The reserves rose by a fifth from March 2020 to June 2021

- The growth may taper, but India’s low reserves days may be over

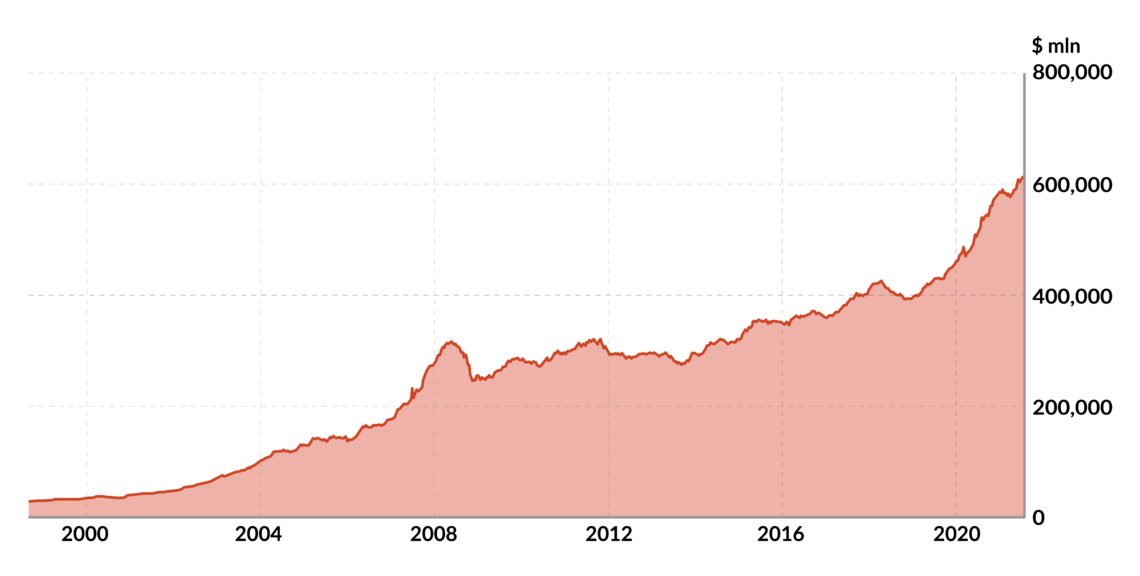

Once chronically short of dollars and pounds, India today has the fourth-largest foreign exchange reserves in the world. Curiously, it has accumulated over $100 billion of its present $610 billion stash in the past 12 months, even while the economy is in recession and the country is struggling with one of the world’s worst Covid outbreaks. New Delhi is wondering if the days of treating reserves as a miser’s hoard should be a thing of the past. There are legitimate concerns about the sustainability of the capital flows that helped generate the present reserve surplus. However, it seems increasingly likely that India’s primary challenge will be modernizing its reserve management and leveraging this bounty to further India’s international ambitions.

Surge in reserves

When the pandemic broke out early last year, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) moved to shore up the country’s reserve position by raising the ceiling on foreign ownership of Indian bonds. Going by the experience of global financial shocks, this made sense. When the 2007-2008 global financial crisis broke out, a flight to safety saw India’s reserves fall $50 billion. Even during crises peripheral to India, such as the 1997 Asian financial crisis, billions of dollars fled the country.

A topsy-turvy economic situation has meant abnormal capital movements.

The central bank need not have worried. Far from being stressed, foreign exchange reserves, which were $487 billion in March 2020 when the Covid crisis first hit, rose rapidly to $608 billion by June 2021. While India has experienced a general rise in its reserves over the past several years, this surge was unprecedented. It took three years for the reserves to go from the $400 billion mark to $500 billion and more than twice that long to accumulate the $100 billion that preceded it.

Capital flows

A topsy-turvy economic situation has meant abnormal capital movements. Foreign direct investment (FDI) remained steady in fiscal 2019 and 2020 at about $55 billion each year. Indians remitting money from overseas, the largest source of external capital, surprised forecasts by dropping only 0.2 percent in 2020, to $83 billion. There was also a considerable compression of imports, thanks to both falling domestic demand and lower oil and gas prices. Indians spent less on travel, education and investment overseas, resulting in outward remittances contracting by $6 billion in fiscal 2021, by a third of the average level. On the negative side, scared foreign investors repatriated $27 billion back home in 2020, about 50 percent more than usual. However, this outflow was dwarfed by the surge in foreign institutional and portfolio investments, which went from $46 billion in 2019-2020 to $117 billion in 2020-2021 and tipped the scales.

Facts & figures

As the Covid pandemic’s economic fallout starts to recede, the question is whether India can continue to expect steady net positive capital flows on this scale. FDI inflows are expected to remain high as growth recovers and market reforms continue to roll out. There has been a persistent increase in FDI flows into India: between 1990 and 2019, they grew at a compounded annual rate of just over 20 percent, a high figure among the major economies. India’s deliberately placed barriers to FDI from China and Hong Kong since the 2019 border clashes do not seem to have had much impact. Inward remittances are expected to start rising again via the large Indian diaspora in the Persian Gulf region (that group sends more money home as the oil prices go up) and the continuing growth of Indian migration to Western countries.

Things can go wrong

The two areas of uncertainty are foreign institutional investments and trade. The Indian stock market is booming largely because of foreign buys. But these are expected to moderate as the United States economy gathers steam and emerging markets lose their luster. There are also obvious structural limitations.

At one point, 70 percent of all external portfolio investment was chasing only 24 blue-chip shares. A more positive side of the story is the growing interest of sovereign wealth funds and pension funds from countries as diverse as Saudi Arabia and Canada. Many of these now have Indian portfolios, and their investments match the likes of private equity firms like Blackstone.

New Delhi also expects that the listing of India on several global bond indices will attract $20-25 billion in annual investments.

India’s primary challenge in the coming years may be in managing the surplus foreign exchange.

Trade has the most significant potential to make India’s foreign exchange fable a balance of payments fairy tale. India ran a trade surplus this June, for the first time in 18 years, but that was a by-product of the country’s severe economic stress. Today exports of software services, petroleum products, jewelry and pharmaceuticals (the country’s traditional strengths) are surging even as large swathes of the economy remain in partial lockdown. The real hope is that a new export-linked cash incentive scheme for different sectors, including electronics and automobiles, will see India develop the sort of value-added goods exports that helped drive East Asia’s economic success.

These would help offset the already growing bill for commodity imports, notably oil and gas. The combination of these factors is why most forecasting sees a net flow of $50 to $60 billion even in fiscal 2021 – despite the expectations that investment funds will begin reinvesting in the U.S. later this year.

Central bank’s challenges

India’s primary foreign exchange challenge in the coming years may be in managing the surplus foreign exchange. Even the present amounts are causing problems for the RBI. In keeping with long-standing Indian policy, the central bank has worked hard to ensure all these capital inflows do not drive up the rupee’s value. The objective has been partly to avoid instability in the currency markets, partly to boost exports, and partly to support ongoing attempts to attract firms trying to relocate their supply chains out of China.

Yet, the RBI has sought to ensure that it does not lose control of its monetary policy when it releases exchanges of the incoming dollars for rupees. The bank tries several ways to get around this. For example, it has placed excess dollars with Indian banks in return for rupees. Result: dollar assets with Indian banks have risen from 220 billion rupees ($2.9. billion) to 2.7 trillion rupees ($36.2 billion) between March 2020 and January 2021.

The Reserve Bank of India remains a black box about the decision-making regarding reserve management.

More complicated has been the central bank’s interventions in spot and forward currency markets to control rupee appreciation. Estimates say the RBI bought somewhere between $80 to $120 billion in forward markets alone. But this comes with a cost. The central bank, in effect, borrowed rupees for one year through these markets and paid 5 percent interest per year to do so. By estimates, these interest payments alone cost 90 billion rupees ($1.2 billion) in the fiscal year 2021.

Economists will recognize that the RBI is becoming entangled in an impossible dilemma. The central bank with an open capital account must choose between targeting exchange rates or domestic money supply; it cannot do both. Its attempts to square this circle are fast becoming costly and distorting the banking system.

Scenarios

India already sees some foreign exchange relief as oil prices start to rise. A sharp shift of investment flows to the U.S. would further ease the pressure. Therefore, the central bank continues to support foreign exchange accumulation, despite the monetary indigestion the excess of dollars is causing. RBI Governor Shaktikanta Das has repeatedly stated that the excessive liquidity in the global economy means capital flows will remain volatile and substantial reserves will be the “best safety net” against international spillovers. India will therefore persist with its present policy until its central bank is sure no major financial storms are coming. That the reserves still only cover 15 months of India’s imports and are just a notch above the country’s entire external debt are further reasons for the central bank to remain cautious.

Under the most feasible scenario, the RBI needs to accept that India’s foreign exchange position today is an entirely new game. As a first step, it needs to become more transparent about these reserves. While reasonably open about its monetary policy deliberations, the RBI remains a black box about the decision-making regarding reserve management. While this may have made some sense when dollars were in short supply, it is counterproductive today. A public framework guiding its foreign currency operations would be an essential first step.

Further down the road is the question of making the rupee a genuine international currency. India’s central bank’s functioning and financial regulations are already closely aligned with those of the West. The rupee is fully convertible on the current account and enjoys de facto convertibility on the capital account – even if the RBI claims otherwise. If the country’s share of global trade and investment continues picking up, India could begin to push for the rupee to be used for cross-border transactions with major economic partners.

Several years ago, IMF officials informally proposed that India consider laying out a 10-year plan to make the rupee a reserve currency included in the IMF’s special drawing rights basket. The Indian side rejected the idea at the time, but it would be a logical way to address its present problems of plenty.