India plans reforms shielded by robust economic growth

India will rely on targeted supply-side spending to help resurrect the country’s Covid-battered growth. Narendra Modi’s government also hopes to implement structural reforms – but those will only work if India’s economic recovery is as strong as expected.

In a nutshell

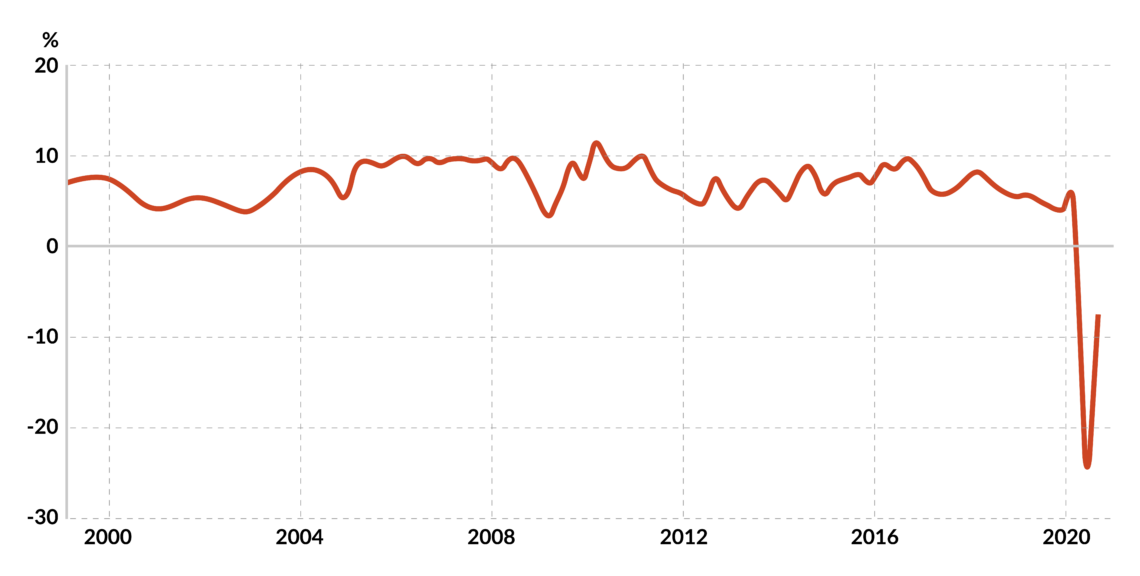

- India’s economy will contract by 7-8 percent due to the crisis, but a strong rebound is expected

- The government scored good marks with citizens for its handling of the pandemic

- Prime Minister Modi is ready to spend this political capital on further reforms

This GIS 2021 Outlook series focuses on the opportunities that stem from the upheaval of the past year.

India’s central government, led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, is emerging from the Covid-19 pandemic in decent but not robust health. It imposed a stringent economic lockdown in March of 2020. New Delhi believes this delayed the peak of the infection rate to September, giving the country time to prepare its healthcare system and develop a treatment protocol.

Though India recorded the world’s fourth-largest number of Covid deaths in absolute terms, the country’s fatality rate – the number of deaths among those who tested positive – was down to 1.44 percent in January, compared to an average of 2.15 percent for the world and 2.4 percent for the European Union. By January’s end, the daily death toll was less than 120 in a country of 1.4 billion.

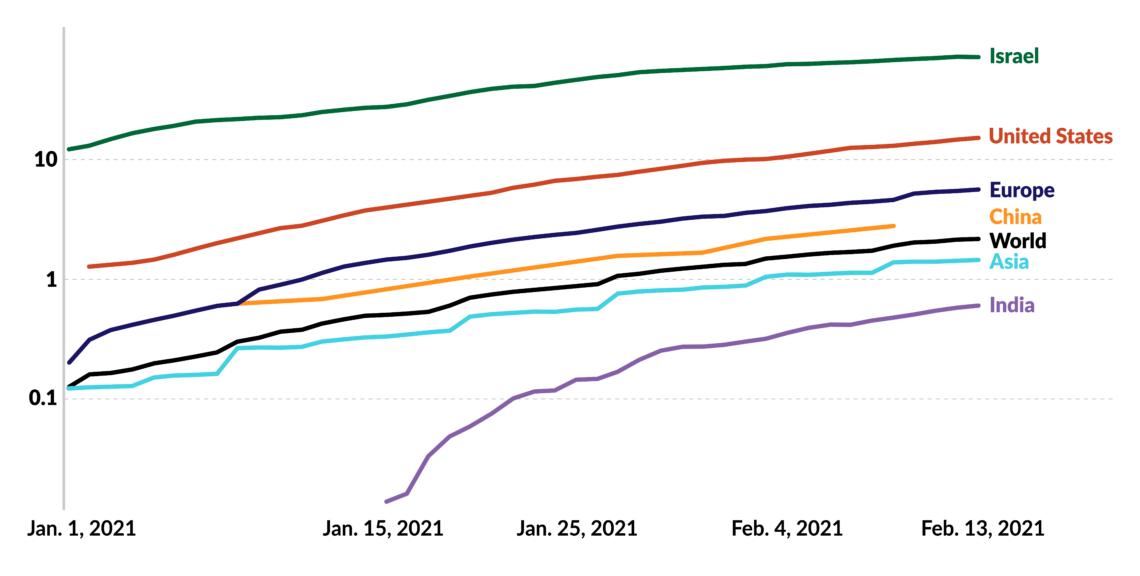

India, a global hub of vaccine production, rolled out anti-Covid jabs and is vaccinating over 100,000 people daily, with ambitions to ramp this up to several million per day.

The first poll of 2021 showed only 8 percent of Indians describing Mr. Modi’s handling of the pandemic as a failure, a sharp drop from August when nearly a quarter of the population was unhappy with his Covid response. The prime minister has emerged from the biggest challenge of his six years in office relatively unscathed.

Facts & figures

For an update, click this link.

The government knows it may yet stumble on the problem of resuscitating an economy that by spring will be about 7 to 8 percent smaller (India’s financial year ends in March). The fiscally conservative prime minister heard strong criticism during the worst of the pandemic for refusing to consider large-scale stimulus packages; he agreed only to funnel extra funds into the welfare system. While Mr. Modi’s popularity remains intact, the economic burden of the crisis is heavy. About half the population rate economic issues, especially unemployment, as the government’s primary failing. Surveys indicate about a fifth of workers remain unemployed, with the formal sector joblessness rate up roughly 10 percentage points.

Economic reforms

For the coming year the government has announced a budget that seeks to resurrect growth through largely supply-side spending: ramp up investments in infrastructure, attract foreign capital, and provide protection for domestic manufactured goods. Low interest rates will allow space for fiscal expansion – the budget has projected a fiscal deficit of 9.5 percent of GDP.

Mr. Modi described his government as ‘pro-market’ and promised to double down on reforms.

Markets responded positively, as an estimated 1.5 percentage points of the total deficit can be attributed to more transparent accounting, and the forecasted 14.4 percent GDP nominal growth rate is seen as credible. The gamble is the government’s decision to contain welfare spending, reduce overall subsidies and push ahead with some unpopular economic reforms. The prime minister and his team bet on a growth boom, inflation remaining moderate and jobs being created fast enough to deflect any social unrest.

Facts & figures

Free-market economists have argued that India’s growth rate was slowing down even before the lockdown because of deep structural problems. Mr. Modi has decided the pandemic presents an opportunity to tackle them – including the most politically risky restructuring that he had avoided or struggled with during his first term. Already in September, he described his government as “pro-market” and promised to double down on reforms.

India’s trade barriers have long been criticized as being antithetical to a market-driven economy. New Delhi officials argue that most of the barriers are aimed at Chinese manufacturing exports and will disappear in five years. Many experts argue, however, that trade actions cannot be country-specific and some of the measures, such as the new quality standards, affect trade with other countries.

The government is moving on many fronts when it comes to reforms. A new labor code consolidating India’s patchwork of laws is almost ready, as are the plans to roll out state-owned firms’ privatization, including large chunks of the banking, oil and transport sectors. Trade unions, including those affiliated with Mr. Modi’s party, have announced plans to hold nationwide protests.

On top of that, there will be a third attempt to break the populist pricing structure that has bedeviled the power sector. The authorities will also attempt to finalize the legal framework for personal data collection (so the digital economy can resume its expansion), as well as change the nature of the financial relationship between the central and state governments to ensure the latter are penalized for fiscal laxity.

The prime minister’s reformist resolve had come to the fore early in the year, when he had to confront tens of thousands of farmers who feared the loss of subsidies from the pro-market farm laws passed in December 2020. They represent a significant step toward improving agricultural productivity and closing a black hole in the government’s finances. Mr. Modi appears ready to face similar protests over the next months.

Politics

The Indian leader has a track record of using a combination of religious nationalism, welfare initiatives and his undeniable charisma to weld together a seemingly impossible coalition of Hindu voters that covers almost the entire spectrum of the country’s caste system. The pandemic has hardly dented the political capital amassed by Mr. Modi. The first public opinion poll of 2021 gives him a 74 percent approval rating, just four percentage points less than where it stood in August last year. If parliamentary elections were held today, his coalition would be projected to lose 32 seats but still retain a healthy majority.

If the prime minister makes a wrong step on the economic front, his standing and that of his government could fray rapidly.

Mr. Modi has been doing what a right-wing government is expected to do. He secures public support by playing on nationalism and identity issues and uses it to push through unpopular economic reforms. However, he walks a tightrope facing opposition from other political parties as well as the economic nationalists in his ruling bloc. His coalition is unwieldy, its unity very dependent on the leader’s personal popularity. If the prime minister makes a wrong step on the economic front, his standing and that of his government could fray rapidly. The farmer protests, for example, will cost his party heavily in two states. This year, several important state elections, including in the fourth largest state of West Bengal, will gauge the prime minister’s popularity prospects over the next two years.

On the external front, the Modi government has only one big question: what happens to the Sino-Indian border standoff when winter ends? New Delhi remains uncertain and keeps 60,000 troops mobilized along its northwestern border. It expects the present border configuration will become the new status quo position over time but does not rule out Chinese punitive action after March. What will remain constant throughout the year is India’s drive to purge its economy of Chinese influence, one motive for its tariff increases.

A lesser concern will be getting a measure of the new United States government. President Joe Biden’s administration will be unenthusiastic about Mr. Modi’s cultural politics but happy with his deep concern about climate change. The real question is how closely India and the U.S. can work together against China on the technological and economic front, given that both governments seek autarkic remedies to boost their respective economies.

Scenarios

The 2021 that Modi will pray for is one marked by double-digit economic growth and concomitant job creation. This would lay the grounds for getting longer-term reforms done with minimal fuss and increase the ruling coalition’s prospects in the five state elections scheduled this year. The icing on the cake would be the return to some kind of equilibrium along the border with China.

The most likely scenario is an economic recovery that unrolls slowly and takes two years to undo the lockdown’s impact. Mr. Modi has the political capital to handle this, but his legislative program would inevitably suffer. He has already offered to put his agricultural reforms in abeyance for 18 months to appease farmers, presumably so he can turn to privatization and other reforms. The leader is not on the ticket in the state elections, and his party is far less popular than he is. A strong election showing is a reasonable expectation, a victory in one or two contests – a bonus. Beijing is likely to avoid more bloodshed on the border, but its aggression may switch to cyberattacks.

The worst-case possibility is one where the economy flounders, and unemployment fails to drop. With the pandemic receding, this could lead to social unrest, local electoral defeats and an emboldened opposition. It is not impossible that Mr. Modi would feel compelled to roll back his agricultural reforms and cancel his privatization plans – as he did with land reforms in 2015. China and Pakistan could both see this as an opportunity to increase pressure on India. In such a case, 2021 would be deemed a second lost year in a row.